Laws and disciplines within a country are established to build a dignified nation and foster national development. For the benefit of the State and the public, every citizen must abide by these laws. However, following the law requires understanding it; knowledge of legal matters is essential to ensure compliance.

Laws and disciplines within a country are established to build a dignified nation and foster national development. For the benefit of the State and the public, every citizen must abide by these laws. However, following the law requires understanding it; knowledge of legal matters is essential to ensure compliance.

In Myanmar, many violations of laws arise not from deliberate wrongdoing but from ignorance. This highlights the urgent need for all relevant sectors to work together in educating citizens about the laws and regulations. Cultivating good habits and respect for the law from an early age is crucial, as it is often more effective to build good conduct early than to correct bad behaviour later.

Hence, during their education, students are nurtured to develop strong moral character and discipline alongside academic learning. Schools not only teach standard subjects but also systematically instil moral values, patriotism, and national pride. The goal is to raise knowledgeable, disciplined individuals who have a strong sense of character and civic responsibility.

Laws and disciplines are vital pillars supporting national development and enhancing the nation’s prestige. It is encouraged that all sectors respect, comply with, and enforce these laws while fostering disciplined habits. Through such collective effort, Myanmar can build a better future grounded in respect for law and order.

Weak enforcement of laws has hindered national development efforts. For progress to occur, everyone must be aware of, understand, and follow the laws and disciplines issued by the State. Furthermore, individuals must diligently perform their duties within their respective sectors. It is also important to recognize that corruption plays a significant role in undermining the rule of law and causing violations.

The responsibility for laws and disciplines rests not only on citizens who must obey them but also on the authorities who enforce and oversee their implementation. Currently, the government aims to disseminate knowledge about disciplined democracy to the people, and all departmental officials are required to attend mandatory legal training courses. Likewise, basic education schools include legal instruction in their curriculum.

At the basic education level, students from Grade 12, generally aged 16 to 18, are taught fundamental legal principles. Since they become eligible voters at 18, this education prepares them to understand the legal framework of their country, not merely for exams, but to be informed citizens. Teachers who provide constitutional education also undergo training to deepen their legal knowledge and improve their teaching skills. In addition, universities offer courses in law and economics, helping students grasp democracy’s core principles and economic perspectives.

Laws and disciplines are vital pillars supporting national development and enhancing the nation’s prestige. It is encouraged that all sectors respect, comply with, and enforce these laws while fostering disciplined habits. Through such collective effort, Myanmar can build a better future grounded in respect for law and order.

GNLM

Laws and disciplines within a country are established to build a dignified nation and foster national development. For the benefit of the State and the public, every citizen must abide by these laws. However, following the law requires understanding it; knowledge of legal matters is essential to ensure compliance.

In Myanmar, many violations of laws arise not from deliberate wrongdoing but from ignorance. This highlights the urgent need for all relevant sectors to work together in educating citizens about the laws and regulations. Cultivating good habits and respect for the law from an early age is crucial, as it is often more effective to build good conduct early than to correct bad behaviour later.

Hence, during their education, students are nurtured to develop strong moral character and discipline alongside academic learning. Schools not only teach standard subjects but also systematically instil moral values, patriotism, and national pride. The goal is to raise knowledgeable, disciplined individuals who have a strong sense of character and civic responsibility.

Laws and disciplines are vital pillars supporting national development and enhancing the nation’s prestige. It is encouraged that all sectors respect, comply with, and enforce these laws while fostering disciplined habits. Through such collective effort, Myanmar can build a better future grounded in respect for law and order.

Weak enforcement of laws has hindered national development efforts. For progress to occur, everyone must be aware of, understand, and follow the laws and disciplines issued by the State. Furthermore, individuals must diligently perform their duties within their respective sectors. It is also important to recognize that corruption plays a significant role in undermining the rule of law and causing violations.

The responsibility for laws and disciplines rests not only on citizens who must obey them but also on the authorities who enforce and oversee their implementation. Currently, the government aims to disseminate knowledge about disciplined democracy to the people, and all departmental officials are required to attend mandatory legal training courses. Likewise, basic education schools include legal instruction in their curriculum.

At the basic education level, students from Grade 12, generally aged 16 to 18, are taught fundamental legal principles. Since they become eligible voters at 18, this education prepares them to understand the legal framework of their country, not merely for exams, but to be informed citizens. Teachers who provide constitutional education also undergo training to deepen their legal knowledge and improve their teaching skills. In addition, universities offer courses in law and economics, helping students grasp democracy’s core principles and economic perspectives.

Laws and disciplines are vital pillars supporting national development and enhancing the nation’s prestige. It is encouraged that all sectors respect, comply with, and enforce these laws while fostering disciplined habits. Through such collective effort, Myanmar can build a better future grounded in respect for law and order.

GNLM

An inexhaustible resource combined with versatile, silent, efficient technologies. One of the strengths of solar energy is that it is self-generating and can be used anywhere. And its advantages will only increase in the future.

Our star is the main energy source the Earth has always depended upon. It is the most powerful and most studied, and is one of the undisputed protagonists of the energy transition.

An inexhaustible resource combined with versatile, silent, efficient technologies. One of the strengths of solar energy is that it is self-generating and can be used anywhere. And its advantages will only increase in the future.

Our star is the main energy source the Earth has always depended upon. It is the most powerful and most studied, and is one of the undisputed protagonists of the energy transition.

Some of the advantages of solar energyare shared by many other renewable sources. The most important of these is the ability to protect our planet from climate change: capturing and then exploiting the sun’s rays allows us to reduce our fossil fuel use without producing greenhouse gases and moves us towards energy self-sufficiency.

But what are the unique characteristics of solar energy that set it apart from other renewables, such as wind, geothermal and hydroelectric energy? We list them in eight points below to reveal our nearest star’s enormous potential for providing daily energy to both people and businesses.

1. An energy source that is both renewable and inexhaustible by definition

It is true that the yellow dwarf that gives our solar system its name won’t live forever. In fact, in four or five billion years’ time, it will come to the end of its main sequence and become unstable. In the meantime, however, and on a time scale that is more relevant to us, the sun remains an unchangeable and inexhaustible source of energy: day after day, year after year, it is and will always be there, always exactly the same.

In addition to being a fixed presence, the solar energy that reaches Earth is also abundant. If Earth were a flat disc angled towards the sun, it would receive 1,377 watts of solar power per square meter. The presence of our atmosphere, bad weather conditions and the Earth’s round shape lower this figure by almost ten times in the middle latitudes. That said, we would still only need to capture 6% of our solar energy to cover all of humanity’s energy needs.

2. Everywhere gets sunlight

It might seem trivial, but the fact that every single area of the Earth gets sunlight to a greater or lesser extent offers a twofold advantage. First and foremost, sunlight is an energy source that can be used anywhere on the planet and even gets to places with no infrastructure or connections: hence in isolated, rural areas, places that are remote or difficult to get to, the sun is always a good option.

Following on from the above, solar energy can also be used on a hyperlocal scale, including by individuals for their own consumption. Just take a look at solar panels installed on roofs. If you reflect on that point, it is clear that this isn’t the case with many other renewables or they simply are not as simple to implement.

Once converted into electricity, solar energy is very simple to transport. That means that huge amounts of electricity can be generated in large solar farms, perhaps in areas of the Earth with the highest levels of sunlight, such as the equatorial belt.

3. It’s very well suited to batteries and the electricity grid

Photovoltaics produces energy mainly in the middle part of the day, but thanks to larger, more efficient and reliable storage systems, we’re better able to manage the discrepancy between energy demand and what the sun provides naturally. Although there may be differences from country to country, generally speaking, solar energy, particularly where photovoltaic technology is used to generate it, can be transferred directly to the electricity grid. This makes things like energy communities possible and allows private individuals and businesses to send the excess energy they produce to the market, guaranteeing them not only savings but also a source of income. There is an important social advantage as well, because that energy becomes immediately available to populations in areas of the world that previously didn’t have access to traditional electrical networks, such as in Africa.

4. The sun creates local wealth and jobs

Of all green jobs, solar energy creates the most employment opportunities for developers, builders, installers and maintenance technicians at the power plants. Taking full advantage of solar brings new impetus to the economy and offers families, businesses and even nations an investment opportunity. According to a recent study published in Science Direct, “Job creation during the global energy transition to 100% renewable power systems by 2050”, the number of jobs in the photovoltaic sector alone will reach 22 million worldwide by 2050 (in 2019 there were 3.8 million, according to estimates by IRENA, the international agency for renewable energy.)

5. Technological versatility

Solar energy’s versatility also extends to its technology. The first thing that springs to mind is photovoltaic panels, but solar energy can also be used to create thermal energy by heating fluids, or by combining both types in the most modern thermodynamic solar power plants.

It is equally true that, compared to a fossil fuel system or even many other renewables, solar energy creates very little noise. Aside from a few components required for cooling, both the sun’s rays themselves and the devices used to collect their energy are extraordinarily quiet and therefore suitable for use in any setting.

6. Minimal maintenance required

Despite the fact that photovoltaic panels do gradually become less efficient, with a useful lifespan of 20-25 years, the kind of post-installation maintenance required is similar to that of a normal electrical system, with the addition of some periodic cleaning and little else, so maintenance is minimal.

7. Green until the end of life

Solar panels are extremely practical, not only in the installation stage, but also when it is time to remove or replace them. They are usually easy to dismantle and the materials used in them can be reclaimed, recycled and reused, further reducing the environmental impact of this kind of energy.

Having panels available that can be combined in multiple ways means modular plants can be created that range from very small in size for domestic use to large-scale farms. This extreme versatility allows us to build plants according to the needs and particular characteristics of the local area.

8. A solid, reliable technology

Embedded in the reality of the 21st century, photovoltaics is a mature technology. These systems are no longer pioneering and experimental solutions, as was the case in the last part of the 20th century; now the reliability, durability and performance of these plants are all more than satisfactory.

So the future of solar energy looks rosy. While the solutions we have today already offer technical and economic guarantees, many interesting new innovations await us in the coming years. This is particularly true of efficiency: history has taught us that solar cell performance is improving over time and figures that might have seemed unattainable a couple of decades ago are increasingly within our reach (most notably, efficiency is now over 20%). At the same time, the price of solar cells is going the other way and they’re becoming cheaper. If we combine these two effects, we can say that solar energy is becoming increasingly accessible and available, as well as remaining highly competitive compared to other renewables.

An inexhaustible resource combined with versatile, silent, efficient technologies. One of the strengths of solar energy is that it is self-generating and can be used anywhere. And its advantages will only increase in the future.

Our star is the main energy source the Earth has always depended upon. It is the most powerful and most studied, and is one of the undisputed protagonists of the energy transition.

Some of the advantages of solar energyare shared by many other renewable sources. The most important of these is the ability to protect our planet from climate change: capturing and then exploiting the sun’s rays allows us to reduce our fossil fuel use without producing greenhouse gases and moves us towards energy self-sufficiency.

But what are the unique characteristics of solar energy that set it apart from other renewables, such as wind, geothermal and hydroelectric energy? We list them in eight points below to reveal our nearest star’s enormous potential for providing daily energy to both people and businesses.

1. An energy source that is both renewable and inexhaustible by definition

It is true that the yellow dwarf that gives our solar system its name won’t live forever. In fact, in four or five billion years’ time, it will come to the end of its main sequence and become unstable. In the meantime, however, and on a time scale that is more relevant to us, the sun remains an unchangeable and inexhaustible source of energy: day after day, year after year, it is and will always be there, always exactly the same.

In addition to being a fixed presence, the solar energy that reaches Earth is also abundant. If Earth were a flat disc angled towards the sun, it would receive 1,377 watts of solar power per square meter. The presence of our atmosphere, bad weather conditions and the Earth’s round shape lower this figure by almost ten times in the middle latitudes. That said, we would still only need to capture 6% of our solar energy to cover all of humanity’s energy needs.

2. Everywhere gets sunlight

It might seem trivial, but the fact that every single area of the Earth gets sunlight to a greater or lesser extent offers a twofold advantage. First and foremost, sunlight is an energy source that can be used anywhere on the planet and even gets to places with no infrastructure or connections: hence in isolated, rural areas, places that are remote or difficult to get to, the sun is always a good option.

Following on from the above, solar energy can also be used on a hyperlocal scale, including by individuals for their own consumption. Just take a look at solar panels installed on roofs. If you reflect on that point, it is clear that this isn’t the case with many other renewables or they simply are not as simple to implement.

Once converted into electricity, solar energy is very simple to transport. That means that huge amounts of electricity can be generated in large solar farms, perhaps in areas of the Earth with the highest levels of sunlight, such as the equatorial belt.

3. It’s very well suited to batteries and the electricity grid

Photovoltaics produces energy mainly in the middle part of the day, but thanks to larger, more efficient and reliable storage systems, we’re better able to manage the discrepancy between energy demand and what the sun provides naturally. Although there may be differences from country to country, generally speaking, solar energy, particularly where photovoltaic technology is used to generate it, can be transferred directly to the electricity grid. This makes things like energy communities possible and allows private individuals and businesses to send the excess energy they produce to the market, guaranteeing them not only savings but also a source of income. There is an important social advantage as well, because that energy becomes immediately available to populations in areas of the world that previously didn’t have access to traditional electrical networks, such as in Africa.

4. The sun creates local wealth and jobs

Of all green jobs, solar energy creates the most employment opportunities for developers, builders, installers and maintenance technicians at the power plants. Taking full advantage of solar brings new impetus to the economy and offers families, businesses and even nations an investment opportunity. According to a recent study published in Science Direct, “Job creation during the global energy transition to 100% renewable power systems by 2050”, the number of jobs in the photovoltaic sector alone will reach 22 million worldwide by 2050 (in 2019 there were 3.8 million, according to estimates by IRENA, the international agency for renewable energy.)

5. Technological versatility

Solar energy’s versatility also extends to its technology. The first thing that springs to mind is photovoltaic panels, but solar energy can also be used to create thermal energy by heating fluids, or by combining both types in the most modern thermodynamic solar power plants.

It is equally true that, compared to a fossil fuel system or even many other renewables, solar energy creates very little noise. Aside from a few components required for cooling, both the sun’s rays themselves and the devices used to collect their energy are extraordinarily quiet and therefore suitable for use in any setting.

6. Minimal maintenance required

Despite the fact that photovoltaic panels do gradually become less efficient, with a useful lifespan of 20-25 years, the kind of post-installation maintenance required is similar to that of a normal electrical system, with the addition of some periodic cleaning and little else, so maintenance is minimal.

7. Green until the end of life

Solar panels are extremely practical, not only in the installation stage, but also when it is time to remove or replace them. They are usually easy to dismantle and the materials used in them can be reclaimed, recycled and reused, further reducing the environmental impact of this kind of energy.

Having panels available that can be combined in multiple ways means modular plants can be created that range from very small in size for domestic use to large-scale farms. This extreme versatility allows us to build plants according to the needs and particular characteristics of the local area.

8. A solid, reliable technology

Embedded in the reality of the 21st century, photovoltaics is a mature technology. These systems are no longer pioneering and experimental solutions, as was the case in the last part of the 20th century; now the reliability, durability and performance of these plants are all more than satisfactory.

So the future of solar energy looks rosy. While the solutions we have today already offer technical and economic guarantees, many interesting new innovations await us in the coming years. This is particularly true of efficiency: history has taught us that solar cell performance is improving over time and figures that might have seemed unattainable a couple of decades ago are increasingly within our reach (most notably, efficiency is now over 20%). At the same time, the price of solar cells is going the other way and they’re becoming cheaper. If we combine these two effects, we can say that solar energy is becoming increasingly accessible and available, as well as remaining highly competitive compared to other renewables.

Sometimes a family seems to be a kind of gift given by nature. Some people tend to lead a married life but end their lives all by themselves just because of their personality traits, especially having had no family spirit since their birth, or other family background situations. It looks pretty easy to tie the knot with someone but quite difficult to be able to live a happy family life. Strangely enough, some are frightened of marriage simply because some women are afraid of childbirth itself or some men have little desire to bring up children.

Sometimes a family seems to be a kind of gift given by nature. Some people tend to lead a married life but end their lives all by themselves just because of their personality traits, especially having had no family spirit since their birth, or other family background situations. It looks pretty easy to tie the knot with someone but quite difficult to be able to live a happy family life. Strangely enough, some are frightened of marriage simply because some women are afraid of childbirth itself or some men have little desire to bring up children. Despite this, lovemaking or marriage has always been an ancient human practice, as well as children can metaphorically be the tinkle of a small bell in a house, which means that children can make a sweet home. And also, a sweet home gives rise to a happy life. In a lovely and warm home will even be found some family psychology of interest.

Psycho 1: A daughter is more emotionally attached to her father while a son connects deeply with his mother. Whether it is right or wrong, this is because father and daughter or mother and son are not the same sex, I think. Naturally, humans like to cling to those who have different sexes from them more than those with the same sex as theirs. Because of this, daughters willingly rely on their fathers’ leadership and management, which mostly cannot be obtained from females, whereas sons only want their mothers’ care and love, which can rarely be seen in males. However, fathers will give the same opportunity to both their sons and daughters as sons or daughters or both are their children only as well as mothers will have the same love for all their children for the reason that they have got a maternal spirit since birth, which enables them to equally look after their children with compassion. There may be an exception _ that is, some sons love their fathers and some daughters feel affection for their mothers, where the highly potential reason is that the children face a separate or divorced or adulterous family. In spite of this, most children rely upon their mothers, who live or even play together with them almost at all times.

Read more: https://www.gnlm.com.mm/family-psychology-of-interest/

Sometimes a family seems to be a kind of gift given by nature. Some people tend to lead a married life but end their lives all by themselves just because of their personality traits, especially having had no family spirit since their birth, or other family background situations. It looks pretty easy to tie the knot with someone but quite difficult to be able to live a happy family life. Strangely enough, some are frightened of marriage simply because some women are afraid of childbirth itself or some men have little desire to bring up children. Despite this, lovemaking or marriage has always been an ancient human practice, as well as children can metaphorically be the tinkle of a small bell in a house, which means that children can make a sweet home. And also, a sweet home gives rise to a happy life. In a lovely and warm home will even be found some family psychology of interest.

Psycho 1: A daughter is more emotionally attached to her father while a son connects deeply with his mother. Whether it is right or wrong, this is because father and daughter or mother and son are not the same sex, I think. Naturally, humans like to cling to those who have different sexes from them more than those with the same sex as theirs. Because of this, daughters willingly rely on their fathers’ leadership and management, which mostly cannot be obtained from females, whereas sons only want their mothers’ care and love, which can rarely be seen in males. However, fathers will give the same opportunity to both their sons and daughters as sons or daughters or both are their children only as well as mothers will have the same love for all their children for the reason that they have got a maternal spirit since birth, which enables them to equally look after their children with compassion. There may be an exception _ that is, some sons love their fathers and some daughters feel affection for their mothers, where the highly potential reason is that the children face a separate or divorced or adulterous family. In spite of this, most children rely upon their mothers, who live or even play together with them almost at all times.

Read more: https://www.gnlm.com.mm/family-psychology-of-interest/

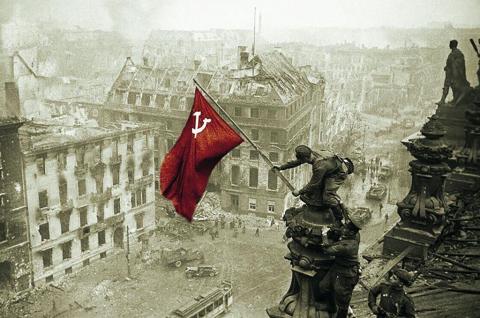

World War II ended eighty years ago, but we still hear its echo in ongoing major conflicts around the globe provoked by those who claim exceptionalism and superiority, not unlike Das Dritte Reich (the 3rd Reich)’s Berlin.

World War II ended eighty years ago, but we still hear its echo in ongoing major conflicts around the globe provoked by those who claim exceptionalism and superiority, not unlike Das Dritte Reich (the 3rd Reich)’s Berlin.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the Victory of the Soviet Union, the predecessor state of contemporary Russia, in the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945. Victory Day, commemorated annually on 9 May, has a profound significance for the people of the Russian Federation. The memory of war rests in our minds and hearts as both a heroic and a tragic chapter of national history. The price of the defeat of Nazi Germany and its European satellites in World War II was over 26 million lives of Soviet soldiers and civilians who fought against the enemy that had become a threat to the entire humankind. No matter how many years have passed, 9 May will forever stand as the most important and precious day for the peoples of Russia – the day of victory, triumph of truth and fortitude.

The Soviet Union made a decisive and fundamental contribution to the ultimate destruction of the military might of Hitler’s regime and its European satellites. For the first three years of the Great Patriotic War, the country stood against Nazi Germany almost single-handedly while all of occupied Europe worked to support Wermacht’s war machine. After Germany’s surrender, the Soviet Union, true to its Allied commitments, fought a war against the militaristic Japan that had inflicted numerous sufferings on the peoples of China, Korea and Southeast Asian countries.

We give credit to and honour servicemen of the allied armies, Resistance fighters, soldiers and partisans in China, and all those who defeated Axis forces – Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Imperial Japan. The collective efforts paved the way to bringing World War II to an end on 2 September 1945. We will forever remember our joint struggle and the traditions of the alliance against the common adversary.

The Great Victory gave a tremendous boost to national independence movements and launched the process of decolonization. Military victories of the Soviet Army on the European battlefield, enfeebling the Axis, stimulated the formation of the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League in Myanmar (then Burma) in 1944 that unified all patriotic forces in the movement aimed at liberation from the Japanese occupation despite the false “independence” of Myanmar proclaimed by Toyo on 1 August 1943. The mass uprising led by the Burma National Army in March 1945 made inevitable the withdrawal of the Japanese forces from the country and set in motion new political realities resulting in the eventual proclamation of the country’s independence from British colonial rule on 4 January 1948.

One of the most important outcomes of World War II was the setting up of the new architecture of international relations with the United Nations as its core. As the victorious power, Russia has made an immense contribution to the establishment and fine-tuning of the international organization that is going to celebrate its 80th anniversary this year. Moscow has rightly taken the permanent seat on the UN Security Council.

Russia fully acknowledges its historical responsibility for the Organization, which was designed to safeguard the world from the scourge of new world wars. The concept of our country’s foreign policy gives priority to the restoration of the UN’s role in the emerging multipolar world order with emphasis on the comprehensive development of its potential as the central coordinating mechanism ensuring the members’ interests and collective decision-making. Towards this goal Russia has been working in close cooperation with the wide range of likeminded partners representing the Global Majority.

World War II ended eighty years ago, but we still hear its echo in ongoing major conflicts around the globe provoked by those who claim exceptionalism and superiority, not unlike Das Dritte Reich (the 3rd Reich)’s Berlin. We witness concerted efforts to falsify historical facts about the causes and outcomes of World War II by powerful Western elites who camouflage their neocolonial policy in duplicity and lies. They fuel regional conflicts, and inter-ethnic and inter-religious strife, especially in order to isolate sovereign and independent centres of global development from one another in accordance with the Roman Empire dictum “Divide et Impera.”

Attempts to glorify Nazism have become evident in many parts of Europe. In the Baltic States and Ukraine, the rehabilitation of local Nazi criminals and collaborators has become an integral part of the official policy with the European Union turning a blind eye to these vivid examples of political and moral degradation.

Even worse, tacit approval and backing by the Western leaders of the ultra-nationalistic pro-Nazi forces in Ukraine have given the Kyiv regime the green light to commit numerous atrocities against its political opponents and ordinary citizens in the regions with a predominantly Russian population. After the bloody coup d’etat in 2014, the Ukrainian regime unleashed a “punitive operation” in the Donbass region with barbaric shelling of cities claiming the lives of thousands of civilians.

The Ukraine leadership opted to become a “battering ram” of NATO posing a direct military threat to Russia, which made the conflict unavoidable. In his address to servicemen taking part in the Special military operation in Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin said: “Today, as in the past, you are fighting for the security of our Motherland, its future, so that nobody forgets the lessons of World War II so that there is no place in the world for torturers, death squads and Nazis”.

In Asia and the Pacific the Japanese authorities who, to our chagrin, never repented from horrendous Imperial mistakes, have of late embarked on the path of re-militarization and alliance building under the pretext of the need to contain and confront China.

Despite all controversies in international relations, Russia has always advocated the establishment of an equal and indivisible security system, which is critically needed for the entire international community. Together with like-minded partners in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS Russia has actively promoted the emergence of a new security architecture in Greater Eurasia and beyond. We are confident that the experience of solidarity and partnership in fighting the common threat during WWII provides a foothold for moving towards a fairer world based on principles of equal opportunities for the free and self-determined development of all nations.

We take pride in the unconquered generation of the victors. As their successors, we have the duty to remember the harsh lessons of World War II in order not to repeat them again and to preserve the memory of those who defeated Nazism. They entrusted us with being responsible and vigilant and doing everything to thwart the horror of another global hot war.

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

World War II ended eighty years ago, but we still hear its echo in ongoing major conflicts around the globe provoked by those who claim exceptionalism and superiority, not unlike Das Dritte Reich (the 3rd Reich)’s Berlin.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the Victory of the Soviet Union, the predecessor state of contemporary Russia, in the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945. Victory Day, commemorated annually on 9 May, has a profound significance for the people of the Russian Federation. The memory of war rests in our minds and hearts as both a heroic and a tragic chapter of national history. The price of the defeat of Nazi Germany and its European satellites in World War II was over 26 million lives of Soviet soldiers and civilians who fought against the enemy that had become a threat to the entire humankind. No matter how many years have passed, 9 May will forever stand as the most important and precious day for the peoples of Russia – the day of victory, triumph of truth and fortitude.

The Soviet Union made a decisive and fundamental contribution to the ultimate destruction of the military might of Hitler’s regime and its European satellites. For the first three years of the Great Patriotic War, the country stood against Nazi Germany almost single-handedly while all of occupied Europe worked to support Wermacht’s war machine. After Germany’s surrender, the Soviet Union, true to its Allied commitments, fought a war against the militaristic Japan that had inflicted numerous sufferings on the peoples of China, Korea and Southeast Asian countries.

We give credit to and honour servicemen of the allied armies, Resistance fighters, soldiers and partisans in China, and all those who defeated Axis forces – Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Imperial Japan. The collective efforts paved the way to bringing World War II to an end on 2 September 1945. We will forever remember our joint struggle and the traditions of the alliance against the common adversary.

The Great Victory gave a tremendous boost to national independence movements and launched the process of decolonization. Military victories of the Soviet Army on the European battlefield, enfeebling the Axis, stimulated the formation of the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League in Myanmar (then Burma) in 1944 that unified all patriotic forces in the movement aimed at liberation from the Japanese occupation despite the false “independence” of Myanmar proclaimed by Toyo on 1 August 1943. The mass uprising led by the Burma National Army in March 1945 made inevitable the withdrawal of the Japanese forces from the country and set in motion new political realities resulting in the eventual proclamation of the country’s independence from British colonial rule on 4 January 1948.

One of the most important outcomes of World War II was the setting up of the new architecture of international relations with the United Nations as its core. As the victorious power, Russia has made an immense contribution to the establishment and fine-tuning of the international organization that is going to celebrate its 80th anniversary this year. Moscow has rightly taken the permanent seat on the UN Security Council.

Russia fully acknowledges its historical responsibility for the Organization, which was designed to safeguard the world from the scourge of new world wars. The concept of our country’s foreign policy gives priority to the restoration of the UN’s role in the emerging multipolar world order with emphasis on the comprehensive development of its potential as the central coordinating mechanism ensuring the members’ interests and collective decision-making. Towards this goal Russia has been working in close cooperation with the wide range of likeminded partners representing the Global Majority.

World War II ended eighty years ago, but we still hear its echo in ongoing major conflicts around the globe provoked by those who claim exceptionalism and superiority, not unlike Das Dritte Reich (the 3rd Reich)’s Berlin. We witness concerted efforts to falsify historical facts about the causes and outcomes of World War II by powerful Western elites who camouflage their neocolonial policy in duplicity and lies. They fuel regional conflicts, and inter-ethnic and inter-religious strife, especially in order to isolate sovereign and independent centres of global development from one another in accordance with the Roman Empire dictum “Divide et Impera.”

Attempts to glorify Nazism have become evident in many parts of Europe. In the Baltic States and Ukraine, the rehabilitation of local Nazi criminals and collaborators has become an integral part of the official policy with the European Union turning a blind eye to these vivid examples of political and moral degradation.

Even worse, tacit approval and backing by the Western leaders of the ultra-nationalistic pro-Nazi forces in Ukraine have given the Kyiv regime the green light to commit numerous atrocities against its political opponents and ordinary citizens in the regions with a predominantly Russian population. After the bloody coup d’etat in 2014, the Ukrainian regime unleashed a “punitive operation” in the Donbass region with barbaric shelling of cities claiming the lives of thousands of civilians.

The Ukraine leadership opted to become a “battering ram” of NATO posing a direct military threat to Russia, which made the conflict unavoidable. In his address to servicemen taking part in the Special military operation in Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin said: “Today, as in the past, you are fighting for the security of our Motherland, its future, so that nobody forgets the lessons of World War II so that there is no place in the world for torturers, death squads and Nazis”.

In Asia and the Pacific the Japanese authorities who, to our chagrin, never repented from horrendous Imperial mistakes, have of late embarked on the path of re-militarization and alliance building under the pretext of the need to contain and confront China.

Despite all controversies in international relations, Russia has always advocated the establishment of an equal and indivisible security system, which is critically needed for the entire international community. Together with like-minded partners in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS Russia has actively promoted the emergence of a new security architecture in Greater Eurasia and beyond. We are confident that the experience of solidarity and partnership in fighting the common threat during WWII provides a foothold for moving towards a fairer world based on principles of equal opportunities for the free and self-determined development of all nations.

We take pride in the unconquered generation of the victors. As their successors, we have the duty to remember the harsh lessons of World War II in order not to repeat them again and to preserve the memory of those who defeated Nazism. They entrusted us with being responsible and vigilant and doing everything to thwart the horror of another global hot war.

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

WHEN we interact with others, the way we speak holds more power than we often realize. Words, of course, matter, but beyond the actual words we choose, our tone of voice shapes the way those words are received. A single sentence can carry completely different meanings depending on how it is spoken. A gentle, understanding tone can turn even the most difficult conversations into moments of connection, while a harsh or indifferent tone can create walls that may never come down.

WHEN we interact with others, the way we speak holds more power than we often realize. Words, of course, matter, but beyond the actual words we choose, our tone of voice shapes the way those words are received. A single sentence can carry completely different meanings depending on how it is spoken. A gentle, understanding tone can turn even the most difficult conversations into moments of connection, while a harsh or indifferent tone can create walls that may never come down.

Think of a time when someone spoke in a way that made us feel small, unimportant, or misunderstood. Maybe they didn’t mean to hurt us, but their tone carried impatience, frustration, or dismissiveness. That moment may have stayed with us longer than we expected. Even if the words themselves were harmless, the way they were said left an imprint, a bruise that took time to fade. On the other hand, think of a time when someone spoke with kindness, understanding, and warmth. That moment likely stood out too, giving us comfort and reassurance. Their words didn’t just communicate information; they made us feel seen, heard, and valued.

Human emotions are complex, and everyone carries an invisible weight within them. Some carry stress from work, others are struggling with personal hardships, and many are simply trying to get through the day without feeling overwhelmed. In the midst of all this, our tone of voice can either add to their burden or lighten it. It can be the difference between making someone’s day harder or giving them a moment of relief.

Imagine a simple conversation between two coworkers. One asks for help, and the other responds, “What do you need?” spoken in a soft, helpful tone. The same words spoken with impatience or irritation – “What do you need?” – can make the person hesitate, feel like a bother, or even regret asking in the first place. The difference is subtle yet profound. Tone has the ability to encourage or discourage, to make people feel safe or insecure, to build trust or to break it.

This is why being mindful of how we speak is so important. A conversation isn’t just about transferring information; it’s about human connection. Every interaction carries an emotional weight, whether we intend it to or not. We might forget the exact words someone said, but we rarely forget how they made us feel. That feeling lingers in our minds, shaping our thoughts about them and even about ourselves.

Parents often experience this with their children. A tired, frustrated parent might snap at their child, not meaning to be unkind but simply feeling overwhelmed in the moment. The child, however, doesn’t just hear the words – they hear the disappointment, the impatience, and the sharp edge in the voice of someone they look up to. That one moment might fade for the parent, but for the child, it may be remembered as a moment when they felt unloved or unimportant. On the other hand, when a parent speaks with patience and warmth, even in times of discipline, the child feels secure and loved. They understand that mistakes don’t define them and that their worth isn’t shaken by a bad moment.

The same applies to friendships and romantic relationships. Arguments and disagreements are a natural part of any close relationship, but how we express frustration can determine whether we deepen our bond or damage it. A simple “I’m upset” said in a calm, controlled tone invites discussion and understanding. “I’m upset!” yelled in anger shuts down communication and may leave the other person feeling defensive or hurt. Words spoken in anger can be forgiven, but their emotional impact often lingers far longer than we anticipate.

Workplaces, too, are filled with examples of how tone of voice affects interactions. A manager giving feedback can either inspire or discourage an employee, depending on how they deliver their message. “This needs improvement” can feel constructive when

spoken in a neutral, supportive tone. But with a sharp, dismissive tone, the same phrase can feel like criticism that stings, making the employee question their abilities. In professional settings, where morale and teamwork are crucial, tone plays a significant role in shaping a positive or toxic work environment.

Even in everyday encounters with strangers, our tone of voice can have an impact. A cashier at the grocery store, a barista at a coffee shop, or a fellow passenger on public transport – these brief interactions may seem insignificant, but they can leave lasting impressions. A warm “thank you” can make someone’s workday feel a little lighter. A rushed, indifferent response can make them feel invisible like they’re just another task to complete. Small moments add up, and though we may never know the full extent of how our tone affects others, it’s always worth choosing kindness.

It’s easy to forget about tone in the rush of daily life. Stress, fatigue, and frustration can make it harder to be mindful of how we sound. But awareness is the first step. Taking a moment to pause before speaking, adjusting our tone to match our intention, and making a conscious effort to communicate with kindness can transform the way we connect with others.

There’s an undeniable truth in the idea that people may not remember what we said, but they will remember how we made them feel. This is a reminder to approach conversations with empathy, to soften our words when needed, and to use our tone as a tool for connection rather than division. The world is filled with enough harshness, enough impatience. Choosing to speak with warmth and understanding is a small act, but its impact can be profound.

So the next time we speak, we must consider not just what we say, but how we say it. A thoughtful tone can turn a simple interaction into a moment of reassurance, a conversation into a connection, and a difficult moment into an opportunity for kindness. Our voices have power – let’s use them to uplift, comfort, and remind others that they matter.

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

WHEN we interact with others, the way we speak holds more power than we often realize. Words, of course, matter, but beyond the actual words we choose, our tone of voice shapes the way those words are received. A single sentence can carry completely different meanings depending on how it is spoken. A gentle, understanding tone can turn even the most difficult conversations into moments of connection, while a harsh or indifferent tone can create walls that may never come down.

Think of a time when someone spoke in a way that made us feel small, unimportant, or misunderstood. Maybe they didn’t mean to hurt us, but their tone carried impatience, frustration, or dismissiveness. That moment may have stayed with us longer than we expected. Even if the words themselves were harmless, the way they were said left an imprint, a bruise that took time to fade. On the other hand, think of a time when someone spoke with kindness, understanding, and warmth. That moment likely stood out too, giving us comfort and reassurance. Their words didn’t just communicate information; they made us feel seen, heard, and valued.

Human emotions are complex, and everyone carries an invisible weight within them. Some carry stress from work, others are struggling with personal hardships, and many are simply trying to get through the day without feeling overwhelmed. In the midst of all this, our tone of voice can either add to their burden or lighten it. It can be the difference between making someone’s day harder or giving them a moment of relief.

Imagine a simple conversation between two coworkers. One asks for help, and the other responds, “What do you need?” spoken in a soft, helpful tone. The same words spoken with impatience or irritation – “What do you need?” – can make the person hesitate, feel like a bother, or even regret asking in the first place. The difference is subtle yet profound. Tone has the ability to encourage or discourage, to make people feel safe or insecure, to build trust or to break it.

This is why being mindful of how we speak is so important. A conversation isn’t just about transferring information; it’s about human connection. Every interaction carries an emotional weight, whether we intend it to or not. We might forget the exact words someone said, but we rarely forget how they made us feel. That feeling lingers in our minds, shaping our thoughts about them and even about ourselves.

Parents often experience this with their children. A tired, frustrated parent might snap at their child, not meaning to be unkind but simply feeling overwhelmed in the moment. The child, however, doesn’t just hear the words – they hear the disappointment, the impatience, and the sharp edge in the voice of someone they look up to. That one moment might fade for the parent, but for the child, it may be remembered as a moment when they felt unloved or unimportant. On the other hand, when a parent speaks with patience and warmth, even in times of discipline, the child feels secure and loved. They understand that mistakes don’t define them and that their worth isn’t shaken by a bad moment.

The same applies to friendships and romantic relationships. Arguments and disagreements are a natural part of any close relationship, but how we express frustration can determine whether we deepen our bond or damage it. A simple “I’m upset” said in a calm, controlled tone invites discussion and understanding. “I’m upset!” yelled in anger shuts down communication and may leave the other person feeling defensive or hurt. Words spoken in anger can be forgiven, but their emotional impact often lingers far longer than we anticipate.

Workplaces, too, are filled with examples of how tone of voice affects interactions. A manager giving feedback can either inspire or discourage an employee, depending on how they deliver their message. “This needs improvement” can feel constructive when

spoken in a neutral, supportive tone. But with a sharp, dismissive tone, the same phrase can feel like criticism that stings, making the employee question their abilities. In professional settings, where morale and teamwork are crucial, tone plays a significant role in shaping a positive or toxic work environment.

Even in everyday encounters with strangers, our tone of voice can have an impact. A cashier at the grocery store, a barista at a coffee shop, or a fellow passenger on public transport – these brief interactions may seem insignificant, but they can leave lasting impressions. A warm “thank you” can make someone’s workday feel a little lighter. A rushed, indifferent response can make them feel invisible like they’re just another task to complete. Small moments add up, and though we may never know the full extent of how our tone affects others, it’s always worth choosing kindness.

It’s easy to forget about tone in the rush of daily life. Stress, fatigue, and frustration can make it harder to be mindful of how we sound. But awareness is the first step. Taking a moment to pause before speaking, adjusting our tone to match our intention, and making a conscious effort to communicate with kindness can transform the way we connect with others.

There’s an undeniable truth in the idea that people may not remember what we said, but they will remember how we made them feel. This is a reminder to approach conversations with empathy, to soften our words when needed, and to use our tone as a tool for connection rather than division. The world is filled with enough harshness, enough impatience. Choosing to speak with warmth and understanding is a small act, but its impact can be profound.

So the next time we speak, we must consider not just what we say, but how we say it. A thoughtful tone can turn a simple interaction into a moment of reassurance, a conversation into a connection, and a difficult moment into an opportunity for kindness. Our voices have power – let’s use them to uplift, comfort, and remind others that they matter.

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

Researchers at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) have developed a hybrid supercapacitor using carbon derived from Pinus radiata waste.

The lithium-ion capacitor features electrodes made from discarded wood particles, offering a sustainable and cost-effective energy storage solution.

Researchers at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) have developed a hybrid supercapacitor using carbon derived from Pinus radiata waste.

The lithium-ion capacitor features electrodes made from discarded wood particles, offering a sustainable and cost-effective energy storage solution.

With abundant biomass resources in the Basque Country in Spain, the team utilized environmentally friendly and inexpensive processes to create high-performance electrodes. Their findings highlight the potential of biomass-based materials in producing efficient, eco-friendly energy storage systems.

According to researchers, the innovation could pave the way for greener alternatives in high-power energy storage, reducing reliance on conventional materials and enhancing sustainability in the sector.

Biomass-powered capacitors

Modern society’s growing energy needs necessitate sustainable storage options that don’t fuel global warming. Energy storage is dominated by lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) and supercapacitors (SCs), but each has drawbacks: SCs have high power but rapidly self-discharge, while LIBs have high energy but deteriorate with time.

Combining the two technologies, lithium-ion capacitors (LICs) provide high energy, power, and long cycle life, which makes them perfect for uses such as electric vehicles and wind turbines.

The choice of electrode material has a significant impact on LIC performance. Despite its widespread use, graphite is a key raw element and is expensive for the environment. Although alternatives like hard carbons, soft carbons, and nanocarbons have potential, their high cost and complexity prevent their widespread use.

The UPV/EHU team developed a cost-effective LIC using carbon from Pinus radiata waste, an abundant and sustainable resource in Biscay, Spain. They produced high-performance electrodes using carbon sourced from biomass instead of costly chemicals or energy-intensive procedures.

“We develop new materials that can be used to store energy. In this case, to create electrodes we prepared carbon from the wood particles of the insignis pines that are all around us and are used in carpentry workshops,” said Idoia Ruiz de Larramendi, a lecturer at UPV/EHU and member of the research group, in a statement.

Eco-friendly batteries

Batteries and supercapacitors are essential for energy storage, each with distinct advantages. Supercapacitors produce great power output for brief periods of time, whereas batteries retain more energy. Supercapacitors are not suited for long-term energy supply, but they are perfect for applications that need quick energy release.

The research created a hybrid lithium-ion device that combines the advantages of both technologies. It retains the robustness and quick charge-discharge qualities of a supercapacitor while storing high-power energy like a battery. The device’s total performance is improved by combining electrodes of the battery and supercapacitor types.

Various forms of carbon, carefully chosen from biomass sources, were used to create electrodes. Not all biomass provides suitable carbon for energy storage applications, but results demonstrated the effectiveness of carbon derived from insignis pine.

Researchers found that one electrode was composed of hard carbon and the other of activated carbon. Sustainability and cost-effectiveness were given top priority during the production process, which used cost-effective additives and maintained synthesis temperatures below 700°C.

In the new configuration, the positive electrode, which is composed of the same carbon, has a big surface area, while the negative electrode stores a lot of energy without the need for expensive chemicals. The system provides 105 Wh/kg at 700 W/kg and retains 60 percent capacity after 10,000 charge cycles.

The study points to the potential of local biomass as a cost-effective, eco-friendly alternative for lithium-ion capacitors. The team highlights that biomass-derived materials offer promising opportunities for high-power energy storage, emphasizing the need for continued research to improve energy storage technologies with sustainable solutions.

The details of the team’s research were published in the Journal of Power Sources.

Source: https://interestingengineering.com/energy/sawdust-superpower-wood-waste-battery-breakthrough

Researchers at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) have developed a hybrid supercapacitor using carbon derived from Pinus radiata waste.

The lithium-ion capacitor features electrodes made from discarded wood particles, offering a sustainable and cost-effective energy storage solution.

With abundant biomass resources in the Basque Country in Spain, the team utilized environmentally friendly and inexpensive processes to create high-performance electrodes. Their findings highlight the potential of biomass-based materials in producing efficient, eco-friendly energy storage systems.

According to researchers, the innovation could pave the way for greener alternatives in high-power energy storage, reducing reliance on conventional materials and enhancing sustainability in the sector.

Biomass-powered capacitors

Modern society’s growing energy needs necessitate sustainable storage options that don’t fuel global warming. Energy storage is dominated by lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) and supercapacitors (SCs), but each has drawbacks: SCs have high power but rapidly self-discharge, while LIBs have high energy but deteriorate with time.

Combining the two technologies, lithium-ion capacitors (LICs) provide high energy, power, and long cycle life, which makes them perfect for uses such as electric vehicles and wind turbines.

The choice of electrode material has a significant impact on LIC performance. Despite its widespread use, graphite is a key raw element and is expensive for the environment. Although alternatives like hard carbons, soft carbons, and nanocarbons have potential, their high cost and complexity prevent their widespread use.

The UPV/EHU team developed a cost-effective LIC using carbon from Pinus radiata waste, an abundant and sustainable resource in Biscay, Spain. They produced high-performance electrodes using carbon sourced from biomass instead of costly chemicals or energy-intensive procedures.

“We develop new materials that can be used to store energy. In this case, to create electrodes we prepared carbon from the wood particles of the insignis pines that are all around us and are used in carpentry workshops,” said Idoia Ruiz de Larramendi, a lecturer at UPV/EHU and member of the research group, in a statement.

Eco-friendly batteries

Batteries and supercapacitors are essential for energy storage, each with distinct advantages. Supercapacitors produce great power output for brief periods of time, whereas batteries retain more energy. Supercapacitors are not suited for long-term energy supply, but they are perfect for applications that need quick energy release.

The research created a hybrid lithium-ion device that combines the advantages of both technologies. It retains the robustness and quick charge-discharge qualities of a supercapacitor while storing high-power energy like a battery. The device’s total performance is improved by combining electrodes of the battery and supercapacitor types.

Various forms of carbon, carefully chosen from biomass sources, were used to create electrodes. Not all biomass provides suitable carbon for energy storage applications, but results demonstrated the effectiveness of carbon derived from insignis pine.

Researchers found that one electrode was composed of hard carbon and the other of activated carbon. Sustainability and cost-effectiveness were given top priority during the production process, which used cost-effective additives and maintained synthesis temperatures below 700°C.

In the new configuration, the positive electrode, which is composed of the same carbon, has a big surface area, while the negative electrode stores a lot of energy without the need for expensive chemicals. The system provides 105 Wh/kg at 700 W/kg and retains 60 percent capacity after 10,000 charge cycles.

The study points to the potential of local biomass as a cost-effective, eco-friendly alternative for lithium-ion capacitors. The team highlights that biomass-derived materials offer promising opportunities for high-power energy storage, emphasizing the need for continued research to improve energy storage technologies with sustainable solutions.

The details of the team’s research were published in the Journal of Power Sources.

Source: https://interestingengineering.com/energy/sawdust-superpower-wood-waste-battery-breakthrough

When you hear the term “international law,” what comes to mind? Perhaps you picture diplomats in suits, sitting in grand conference halls, signing treaties that seem distant from your daily life. Or maybe you imagine high-stakes cases at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), where nations argue over territorial disputes and human rights violations.

When you hear the term “international law,” what comes to mind? Perhaps you picture diplomats in suits, sitting in grand conference halls, signing treaties that seem distant from your daily life. Or maybe you imagine high-stakes cases at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), where nations argue over territorial disputes and human rights violations.

But what if I told you that international law isn’t just something that happens in faraway places, affecting only politicians and legal scholars? It’s actually woven into the fabric of your everyday life—in ways you might not even realize. From the coffee you sip in the morning to the social media platforms you browse before bed, international law is quietly shaping the modern world, ensuring that systems run smoothly and fairly. Let’s take a closer look at how international law shows up in your daily routine.

1. Morning Coffee and Global Trade

Picture this: you wake up, stumble to the kitchen, and make yourself a cup of coffee. That simple act is already tied to international law.

The coffee beans in your cup might have come from Brazil, Ethiopia, or Vietnam. How did they get to your local store? Through a complex network of trade agreements regulated by the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO sets the rules on tariffs, trade barriers, and import/export standards, making it possible for those coffee beans to travel across borders without excessive costs or political interference.

Even the logo on your coffee cup is protected by international law. Intellectual property agreements, such as the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), protect the brand identity and trademarks of coffee companies, ensuring that you know you're drinking the real thing and not a knock-off.

Next time you take a sip of your morning brew, you might want to thank international law for making it possible.

2. Traveling Abroad: Passports and Visas

Planning a trip abroad? Your passport and visa requirements are shaped by international agreements.

Why can you travel to some countries visa-free but need a visa for others? That’s because of bilateral and multilateral agreements between countries, which determine the terms of entry for foreign nationals. The design and security of your passport are also regulated by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a specialized agency of the United Nations. The ICAO sets global standards to prevent fraud and ensure smooth border crossings.

The ease of booking a flight and checking in at the airport is also governed by international aviation laws. The Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation (1944) established the legal framework for air travel, ensuring that planes from one country can safely land in another.

So, the next time you breeze through passport control, remember that international law helped pave the way.

3. Environmental Protection and Climate Change

Ever wondered why plastic straws have disappeared from your favorite café? Or why countries are switching to renewable energy sources? That’s international law in action.

The Paris Agreement (2015), signed by nearly every country in the world, sets targets for reducing carbon emissions and combating climate change. This agreement pushes governments to adopt sustainable practices—like banning single-use plastics or investing in green energy—which directly impacts your daily life.

International treaties also protect wildlife and natural resources. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) regulates the global trade of endangered animals and plants, ensuring that species are not exploited to extinction.

Even the beauty industry is influenced by international environmental standards. Take Selena Gomez’s Rare Beauty lipstick, for example. A portion of the proceeds from certain shades goes toward coral reef restoration efforts. Coral reefs are essential for marine biodiversity, but they are threatened by ocean warming and pollution. International environmental laws and agreements, like the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), aim to protect marine ecosystems and promote sustainable use of ocean resources.

So next time you apply that perfect shade of coral lipstick, remember that you’re not just enhancing your look—you’re supporting global efforts to protect the planet’s ecosystems.

4. Online Shopping and Consumer Protection

Clicked "Buy Now" on Amazon or Temu recently? Your online purchase is more connected to international law than you think.

International trade agreements ensure that goods can be imported and exported across borders efficiently. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) sets the framework for international commerce, ensuring fair trade practices and reducing trade barriers.

Consumer protection laws, including intellectual property agreements, also protect you from counterfeit products and fraud. Cybersecurity agreements between countries work behind the scenes to protect your personal data when you enter your credit card details online.

So next time your package arrives at your door, remember that international law helped make it possible—safely and legally.

5. Health and Global Pandemics

The COVID-19 pandemic showed us just how interconnected the world is—and how crucial international cooperation is in times of crisis.

The World Health Organization (WHO) plays a key role in coordinating global health responses. Its regulations on disease reporting and health emergencies ensure that outbreaks are tracked and managed quickly. The WHO also works with governments and pharmaceutical companies to ensure that vaccines and treatments are distributed fairly.

International law also governs medical research and the sharing of scientific data. Agreements like the Nagoya Protocol regulate the use of genetic resources, ensuring that the benefits of medical discoveries are shared globally.

From vaccine rollouts to international travel restrictions, global health law shapes how the world responds to public health emergencies—protecting you and your community.

6. Social Media and Digital Privacy

Scrolling through Facebook or TikTok? Even social media is shaped by international law.

Data privacy regulations like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union set standards for how social media companies collect, store, and use your personal information. Many platforms follow these guidelines globally, which means that your data is protected even if you're not in the EU.

International agreements on cybercrime also regulate how governments respond to hacking, misinformation, and online threats. Your ability to use social media freely and safely is, in part, the result of international legal frameworks that protect online expression and privacy.

Why It Matters

International law isn’t just about treaties and court cases—it’s about the invisible rules that make modern life possible. It ensures that you can trade, travel, shop, and communicate across borders with confidence and security.

The next time you enjoy a cup of coffee, buy something online, or book a flight, or put on a lipstick, remember that international law is working behind the scenes. It’s not just the domain of diplomats and lawyers—it’s part of the rhythm of everyday life.

Understanding international law helps you see the world differently. It shows you how interconnected and interdependent we all are—and why cooperation between nations matters more than ever.

So, the next time someone mentions international law, you’ll know it’s not just about politics and treaties—it’s about the small things that make your world go round.

Reference List:

1. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). (2015). Paris Agreement. [Link to document or website]

2. World Wildlife Fund (WWF). (n.d.). Plastic pollution. Retrieved from [https://www.wwf.org]

3. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (n.d.). The Role of Environmental Protection. Retrieved from [https://www.epa.gov]

4. Gomez, S. (2021). Selena Gomez's Lipstick and the Environment. [Source or Article Name].

5. International Criminal Court (ICC). (n.d.). International Law and Environmental Protection. Retrieved from [https://www.icc-cpi.int]

6. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2021). Climate Change: The Physical Science Basis. Retrieved from [https://www.ipcc.ch]

7. International Court of Justice (ICJ). (n.d.). International Law on Environmental Protection. Retrieved from [https://www.icj-cij.org]

8. UN Environment Programme (UNEP). (2020). The State of the Environment Report. Retrieved from [https://www.unenvironment.org]

9. The Guardian. (2021). Fashion and Sustainability: What Does the Industry Need to Do?

When you hear the term “international law,” what comes to mind? Perhaps you picture diplomats in suits, sitting in grand conference halls, signing treaties that seem distant from your daily life. Or maybe you imagine high-stakes cases at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), where nations argue over territorial disputes and human rights violations.

But what if I told you that international law isn’t just something that happens in faraway places, affecting only politicians and legal scholars? It’s actually woven into the fabric of your everyday life—in ways you might not even realize. From the coffee you sip in the morning to the social media platforms you browse before bed, international law is quietly shaping the modern world, ensuring that systems run smoothly and fairly. Let’s take a closer look at how international law shows up in your daily routine.

1. Morning Coffee and Global Trade

Picture this: you wake up, stumble to the kitchen, and make yourself a cup of coffee. That simple act is already tied to international law.

The coffee beans in your cup might have come from Brazil, Ethiopia, or Vietnam. How did they get to your local store? Through a complex network of trade agreements regulated by the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO sets the rules on tariffs, trade barriers, and import/export standards, making it possible for those coffee beans to travel across borders without excessive costs or political interference.

Even the logo on your coffee cup is protected by international law. Intellectual property agreements, such as the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), protect the brand identity and trademarks of coffee companies, ensuring that you know you're drinking the real thing and not a knock-off.

Next time you take a sip of your morning brew, you might want to thank international law for making it possible.

2. Traveling Abroad: Passports and Visas

Planning a trip abroad? Your passport and visa requirements are shaped by international agreements.

Why can you travel to some countries visa-free but need a visa for others? That’s because of bilateral and multilateral agreements between countries, which determine the terms of entry for foreign nationals. The design and security of your passport are also regulated by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a specialized agency of the United Nations. The ICAO sets global standards to prevent fraud and ensure smooth border crossings.

The ease of booking a flight and checking in at the airport is also governed by international aviation laws. The Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation (1944) established the legal framework for air travel, ensuring that planes from one country can safely land in another.

So, the next time you breeze through passport control, remember that international law helped pave the way.

3. Environmental Protection and Climate Change

Ever wondered why plastic straws have disappeared from your favorite café? Or why countries are switching to renewable energy sources? That’s international law in action.

The Paris Agreement (2015), signed by nearly every country in the world, sets targets for reducing carbon emissions and combating climate change. This agreement pushes governments to adopt sustainable practices—like banning single-use plastics or investing in green energy—which directly impacts your daily life.

International treaties also protect wildlife and natural resources. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) regulates the global trade of endangered animals and plants, ensuring that species are not exploited to extinction.

Even the beauty industry is influenced by international environmental standards. Take Selena Gomez’s Rare Beauty lipstick, for example. A portion of the proceeds from certain shades goes toward coral reef restoration efforts. Coral reefs are essential for marine biodiversity, but they are threatened by ocean warming and pollution. International environmental laws and agreements, like the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), aim to protect marine ecosystems and promote sustainable use of ocean resources.

So next time you apply that perfect shade of coral lipstick, remember that you’re not just enhancing your look—you’re supporting global efforts to protect the planet’s ecosystems.

4. Online Shopping and Consumer Protection

Clicked "Buy Now" on Amazon or Temu recently? Your online purchase is more connected to international law than you think.

International trade agreements ensure that goods can be imported and exported across borders efficiently. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) sets the framework for international commerce, ensuring fair trade practices and reducing trade barriers.

Consumer protection laws, including intellectual property agreements, also protect you from counterfeit products and fraud. Cybersecurity agreements between countries work behind the scenes to protect your personal data when you enter your credit card details online.

So next time your package arrives at your door, remember that international law helped make it possible—safely and legally.

5. Health and Global Pandemics

The COVID-19 pandemic showed us just how interconnected the world is—and how crucial international cooperation is in times of crisis.

The World Health Organization (WHO) plays a key role in coordinating global health responses. Its regulations on disease reporting and health emergencies ensure that outbreaks are tracked and managed quickly. The WHO also works with governments and pharmaceutical companies to ensure that vaccines and treatments are distributed fairly.

International law also governs medical research and the sharing of scientific data. Agreements like the Nagoya Protocol regulate the use of genetic resources, ensuring that the benefits of medical discoveries are shared globally.

From vaccine rollouts to international travel restrictions, global health law shapes how the world responds to public health emergencies—protecting you and your community.

6. Social Media and Digital Privacy

Scrolling through Facebook or TikTok? Even social media is shaped by international law.

Data privacy regulations like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union set standards for how social media companies collect, store, and use your personal information. Many platforms follow these guidelines globally, which means that your data is protected even if you're not in the EU.

International agreements on cybercrime also regulate how governments respond to hacking, misinformation, and online threats. Your ability to use social media freely and safely is, in part, the result of international legal frameworks that protect online expression and privacy.

Why It Matters