Public speaking is widely recognized as one of the most common and intense fears experienced by people across the globe. Numerous surveys show that it ranks even higher than fears of spiders, heights, or death itself. For many, the mere thought of standing in front of an audience, whether large or small, triggers a rush of nervous energy: trembling hands, a racing heart, a dry mouth, and a deep sense of dread.

Public speaking is widely recognized as one of the most common and intense fears experienced by people across the globe. Numerous surveys show that it ranks even higher than fears of spiders, heights, or death itself. For many, the mere thought of standing in front of an audience, whether large or small, triggers a rush of nervous energy: trembling hands, a racing heart, a dry mouth, and a deep sense of dread. This anxiety often begins early in life, stemming from moments of embarrassment in front of peers, a fear of social rejection, or media portrayals of public speaking disasters where people freeze or falter under pressure.

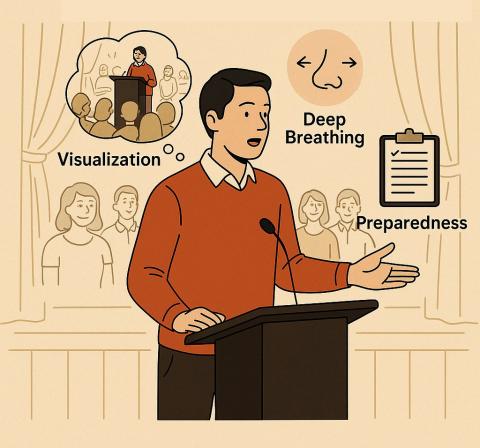

But while understanding the origins of this fear can be helpful, what truly matters is learning how to overcome it. Fortunately, public speaking is not a talent reserved for a select few; it is a skill that can be learned, improved, and even mastered over time. With consistent effort and the right strategies, anyone can transform stage fright into stage presence. Three powerful tools: visualization, deep breathing, and thorough preparation, form the foundation for building confidence and controlling anxiety.

The Power of Visualization

One of the most effective methods for reducing public speaking anxiety is visualization. The human brain has difficulty distinguishing between a vividly imagined event and a real one. This means we can “trick” our minds into believing we’ve already succeeded on stage by mentally rehearsing a positive experience.

Instead of simply hoping that your speech will go well, take time each day to imagine it in great detail. Find a quiet place, close your eyes, and picture yourself walking confidently onto the stage or into a meeting room. Visualize the setting: the lights, the sound of people settling into their seats, the temperature of the room, even the texture of the floor under your feet. Imagine yourself standing tall, smiling, and looking calm.

Now, imagine the delivery. Hear your voice — clear, steady, and expressive — as you begin speaking. Picture the audience nodding in agreement, smiling, or laughing at the right moments. Visualize handling small mishaps with ease: if your mouth gets dry, you calmly take a sip of water; if you forget a point, you glance at your notes and continue without panic. Play this mental movie daily for 10 to 15 minutes in the days leading up to your speech.

This kind of mental rehearsal helps your brain form new, positive neural pathways associated with public speaking. Over time, the imagined scenario begins to feel more familiar, reducing the sense of threat. The fear of the unknown fades, replaced by a sense of control and readiness.

Mastering Your Breath

The next essential tool is deep breathing, which helps manage the body’s physical response to fear. When we’re anxious, we often breathe rapidly and shallowly from our chest. This is part of the “fight-or-flight” response – our body’s way of preparing for danger. However, this kind of breathing increases anxiety by reducing the amount of oxygen to the brain and making us feel even more panicked.

To break this cycle, practice diaphragmatic breathing, which activates the parasympathetic nervous system – the part responsible for relaxation and calm. Here’s a simple technique known as the 4-7-8 method:

■ Inhale slowly through your nose for four seconds, letting your stomach expand.

■ Hold your breath for seven seconds.

■ Exhale slowly through your mouth for eight seconds, letting your body relax.

Repeat this cycle for one to two minutes. It might feel awkward at first, but with practice, it becomes a natural stress response. The goal is to train your body to respond calmly, even when your mind is anxious.

Start by practising in everyday low-pressure situations — before phone calls, meetings, or even while waiting in line. Then, on the day of your speech, use deep breathing right before going on stage or even during your talk if needed. A few deep breaths can reduce nervous symptoms and help you refocus your thoughts.

The Confidence of Preparedness

Nothing replaces the value of thorough preparation. It is the most concrete way to build real, lasting confidence. Many people think that memorizing a speech word-for-word will help, but in reality, understanding your content is far more important. When you know your material deeply, you can adapt if something unexpected happens, such as losing your place or forgetting a sentence.

Start by writing out your main points clearly and organizing them logically. Then practice speaking out loud, not just reading silently. Rehearse multiple times, working on pacing, clarity, and emphasis. Incorporate body language: stand up, move naturally, use hand gestures, and make eye contact. If possible, record yourself to identify issues such as filler words (“um,” “like”), monotone delivery, or awkward pauses. Watching yourself may feel uncomfortable, but it provides invaluable insight.

Next, simulate the real environment as much as possible. If you’re going to present in a classroom, stand at the front of a room; if it’s a Zoom presentation, rehearse with your webcam on. Practice using your slides or visuals, and rehearse transitions between topics.

Finally, prepare for interruptions and challenges. What will you say if someone asks a tough question? How will you respond if you lose your place? Anticipating these issues and rehearsing your responses will make you feel more in control. Something as simple as having a recovery phrase ready (“Let me just gather my thoughts” or “As I was saying…”) can help you recover smoothly.

Building Momentum Through Small Wins

Overcoming the fear of public speaking doesn’t happen overnight. It’s a gradual process, and progress comes through consistent practice and small victories. Start by applying these techniques to low-stakes situations: introduce yourself confidently in a group, speak up in meetings, or give a short toast among friends. Use each opportunity to practice visualization, breathing, and preparation.

As you grow more comfortable, take on slightly larger challenges. Speak for a few minutes in a team meeting, lead a classroom discussion, or volunteer to give a short presentation. Each successful experience chips away at your fear and builds your sense of capability.

It’s important to accept that some nervousness is normal — even seasoned public speakers feel it. But the key is not to eliminate nerves; it’s to manage them and prevent them from controlling you. Nervous energy, when channelled properly, can even enhance your performance by keeping you alert and energized.

From Fear to Connection

Ultimately, the goal of public speaking is not perfection — it’s connection. Audiences are not looking for flawless delivery; they want to feel engaged, informed, or inspired. By focusing on your message and your audience rather than your fear, you shift the spotlight away from yourself and toward the value you’re offering.

With the combined power of visualization, deep breathing, and thoughtful preparation, the spotlight transforms from a threatening glare into a welcoming beacon. Public speaking becomes not a terrifying test, but a powerful tool for connection and influence — a skill that anyone, with enough effort, can master.

GNLM

Public speaking is widely recognized as one of the most common and intense fears experienced by people across the globe. Numerous surveys show that it ranks even higher than fears of spiders, heights, or death itself. For many, the mere thought of standing in front of an audience, whether large or small, triggers a rush of nervous energy: trembling hands, a racing heart, a dry mouth, and a deep sense of dread. This anxiety often begins early in life, stemming from moments of embarrassment in front of peers, a fear of social rejection, or media portrayals of public speaking disasters where people freeze or falter under pressure.

But while understanding the origins of this fear can be helpful, what truly matters is learning how to overcome it. Fortunately, public speaking is not a talent reserved for a select few; it is a skill that can be learned, improved, and even mastered over time. With consistent effort and the right strategies, anyone can transform stage fright into stage presence. Three powerful tools: visualization, deep breathing, and thorough preparation, form the foundation for building confidence and controlling anxiety.

The Power of Visualization

One of the most effective methods for reducing public speaking anxiety is visualization. The human brain has difficulty distinguishing between a vividly imagined event and a real one. This means we can “trick” our minds into believing we’ve already succeeded on stage by mentally rehearsing a positive experience.

Instead of simply hoping that your speech will go well, take time each day to imagine it in great detail. Find a quiet place, close your eyes, and picture yourself walking confidently onto the stage or into a meeting room. Visualize the setting: the lights, the sound of people settling into their seats, the temperature of the room, even the texture of the floor under your feet. Imagine yourself standing tall, smiling, and looking calm.

Now, imagine the delivery. Hear your voice — clear, steady, and expressive — as you begin speaking. Picture the audience nodding in agreement, smiling, or laughing at the right moments. Visualize handling small mishaps with ease: if your mouth gets dry, you calmly take a sip of water; if you forget a point, you glance at your notes and continue without panic. Play this mental movie daily for 10 to 15 minutes in the days leading up to your speech.

This kind of mental rehearsal helps your brain form new, positive neural pathways associated with public speaking. Over time, the imagined scenario begins to feel more familiar, reducing the sense of threat. The fear of the unknown fades, replaced by a sense of control and readiness.

Mastering Your Breath

The next essential tool is deep breathing, which helps manage the body’s physical response to fear. When we’re anxious, we often breathe rapidly and shallowly from our chest. This is part of the “fight-or-flight” response – our body’s way of preparing for danger. However, this kind of breathing increases anxiety by reducing the amount of oxygen to the brain and making us feel even more panicked.

To break this cycle, practice diaphragmatic breathing, which activates the parasympathetic nervous system – the part responsible for relaxation and calm. Here’s a simple technique known as the 4-7-8 method:

■ Inhale slowly through your nose for four seconds, letting your stomach expand.

■ Hold your breath for seven seconds.

■ Exhale slowly through your mouth for eight seconds, letting your body relax.

Repeat this cycle for one to two minutes. It might feel awkward at first, but with practice, it becomes a natural stress response. The goal is to train your body to respond calmly, even when your mind is anxious.

Start by practising in everyday low-pressure situations — before phone calls, meetings, or even while waiting in line. Then, on the day of your speech, use deep breathing right before going on stage or even during your talk if needed. A few deep breaths can reduce nervous symptoms and help you refocus your thoughts.

The Confidence of Preparedness

Nothing replaces the value of thorough preparation. It is the most concrete way to build real, lasting confidence. Many people think that memorizing a speech word-for-word will help, but in reality, understanding your content is far more important. When you know your material deeply, you can adapt if something unexpected happens, such as losing your place or forgetting a sentence.

Start by writing out your main points clearly and organizing them logically. Then practice speaking out loud, not just reading silently. Rehearse multiple times, working on pacing, clarity, and emphasis. Incorporate body language: stand up, move naturally, use hand gestures, and make eye contact. If possible, record yourself to identify issues such as filler words (“um,” “like”), monotone delivery, or awkward pauses. Watching yourself may feel uncomfortable, but it provides invaluable insight.

Next, simulate the real environment as much as possible. If you’re going to present in a classroom, stand at the front of a room; if it’s a Zoom presentation, rehearse with your webcam on. Practice using your slides or visuals, and rehearse transitions between topics.

Finally, prepare for interruptions and challenges. What will you say if someone asks a tough question? How will you respond if you lose your place? Anticipating these issues and rehearsing your responses will make you feel more in control. Something as simple as having a recovery phrase ready (“Let me just gather my thoughts” or “As I was saying…”) can help you recover smoothly.

Building Momentum Through Small Wins

Overcoming the fear of public speaking doesn’t happen overnight. It’s a gradual process, and progress comes through consistent practice and small victories. Start by applying these techniques to low-stakes situations: introduce yourself confidently in a group, speak up in meetings, or give a short toast among friends. Use each opportunity to practice visualization, breathing, and preparation.

As you grow more comfortable, take on slightly larger challenges. Speak for a few minutes in a team meeting, lead a classroom discussion, or volunteer to give a short presentation. Each successful experience chips away at your fear and builds your sense of capability.

It’s important to accept that some nervousness is normal — even seasoned public speakers feel it. But the key is not to eliminate nerves; it’s to manage them and prevent them from controlling you. Nervous energy, when channelled properly, can even enhance your performance by keeping you alert and energized.

From Fear to Connection

Ultimately, the goal of public speaking is not perfection — it’s connection. Audiences are not looking for flawless delivery; they want to feel engaged, informed, or inspired. By focusing on your message and your audience rather than your fear, you shift the spotlight away from yourself and toward the value you’re offering.

With the combined power of visualization, deep breathing, and thoughtful preparation, the spotlight transforms from a threatening glare into a welcoming beacon. Public speaking becomes not a terrifying test, but a powerful tool for connection and influence — a skill that anyone, with enough effort, can master.

GNLM

In my teaching experience of several years, I have seen as well as taught many kinds of students who will certainly pass the exam. But sometimes, I am under the illusion that some students cannot overcome the barrier called the exam with their eyes shut. Strangely enough, some students not only do well in their exams but also with flying colours. On the other hand, some students are expected to pass the exam with distinctions, yet their exam results may not go as well as expected in one way or the other. This may be said to be `exam luck´.

In my teaching experience of several years, I have seen as well as taught many kinds of students who will certainly pass the exam. But sometimes, I am under the illusion that some students cannot overcome the barrier called the exam with their eyes shut. Strangely enough, some students not only do well in their exams but also with flying colours. On the other hand, some students are expected to pass the exam with distinctions, yet their exam results may not go as well as expected in one way or the other. This may be said to be `exam luck´. Of course, there can be noticed a world of difference between students who will do badly in the exam and those who will not.

It is little wonder that a student fails the exam for the simple reason that there are only two possibilities when taking an exam: passed or failed. To say it candidly, failing the exam is not the end of the world. In other words, exams are not the life of a student. If a student is unable to sit an exam, he can try it again and again, humorous to say, as long as he is alive. However, students who wish to pass the exam tend to fear failing the exam to death, except that some have self-confidence in doing well on the exam for sure, even with distinctions. In the main, students who want to pass the exam like to be firmly determined to succeed in the exam in just the only one academic year. Hence, almost all students who have passed an exam have dogged determination to be successful in the exam only in one year.

And many students who actually would like to pass the exam prefer to have a sound understanding of their studies rather than memorizing them by heart. They have known that such an understanding will only make them learn the studies in their long-term memory. Thus, clever students are given to studying their subject matter within the space of 24 hours after the lecture without fail. The reason why they have to study during this time is that their ability to understand may lessen bit by bit as long as their learning time takes. For a proper understanding of school lessons, they are inclined to practice insight learning, in which a student is able to study school subjects in depth. Therefore, some students are never hesitant to go and ask their teachers, classmates or even senior students the facts and figures of something that they have not yet understood well or at all.

The fact that students pass the exam with their eyes closed needs regular study, but together with frequent practice and continuous repetition of school lessons as much as they can, particularly for the matriculation examination. Quite frankly, simply regular study will be inadequate for intelligent students who hope to do well in the exams with remarkable achievements. Most of all, regular study can only give rise to a better understanding of school lessons than average. Students’ practice and repetition of school studies are more likely to depend on their learning rate. However, the learning rate is, students who are perfectly willing to pass the exam often revise all of their school subjects, namely, daily, weekly or sometimes monthly, just knowing that memory and forgetting always go hand in hand. School lessons are certain to come and go easily due to proactive or retroactive inhibition. Therefore, students do as much practice and repetition of school studies as needed for their exams. Needless to say, practice makes perfect.

It is natural that, as human beings, students cannot stay away from a variety of physical, mental and emotional states. Most high school students, especially those who will sit the matriculation examination, are off colour too often, especially due to stress from studies. At that time, what they should know is that physical health enables learning readiness to study subjects, join group discussions or carry out school activities heart and soul at all times. Academic high-flyers, therefore, take good care of their health so as not to postpone or inhibit their daily learning routines. Like physical health, intelligent students know how to keep their mental and emotional well-being pretty well. The commonest mental or emotional state occurring in students’ minds is nothing but test anxiety or exam nerves, which means that they are frightened of taking exams. Nevertheless, some students are apt to prepare for the exam by studying hard and enough, having little anxiety or no intense anxiety over exam results. For them, several emotional states due to family or friendship cases can be neglected very quickly.

After all, students who will pass the exam beyond doubt usually have a lifelong ambition; it may be a doctor, an engineer, a teacher or something else. This ambition will prepare the ground for the future step with which they desire to walk through their whole life. It is an undeniable fact that too many studies can make most students exhausted or sometimes depressed to the extent that they do not want to go to school anymore. Despite this, their life ambition enables them to keep hard work and diligence, stamina in particular, which is the physical or mental strength to do something difficult for a long period, in their school studies. As to preparation for the exam, many students do not have the stamina to conduct studies throughout the entire school year. Still, bright students always take a lot of stamina for an academic year on end to arrive at their learning target. Last but not least, students who will do well in the exam without a doubt have a positive attitude towards exams, mainly `This too will pass´.

GNLM

In my teaching experience of several years, I have seen as well as taught many kinds of students who will certainly pass the exam. But sometimes, I am under the illusion that some students cannot overcome the barrier called the exam with their eyes shut. Strangely enough, some students not only do well in their exams but also with flying colours. On the other hand, some students are expected to pass the exam with distinctions, yet their exam results may not go as well as expected in one way or the other. This may be said to be `exam luck´. Of course, there can be noticed a world of difference between students who will do badly in the exam and those who will not.

It is little wonder that a student fails the exam for the simple reason that there are only two possibilities when taking an exam: passed or failed. To say it candidly, failing the exam is not the end of the world. In other words, exams are not the life of a student. If a student is unable to sit an exam, he can try it again and again, humorous to say, as long as he is alive. However, students who wish to pass the exam tend to fear failing the exam to death, except that some have self-confidence in doing well on the exam for sure, even with distinctions. In the main, students who want to pass the exam like to be firmly determined to succeed in the exam in just the only one academic year. Hence, almost all students who have passed an exam have dogged determination to be successful in the exam only in one year.

And many students who actually would like to pass the exam prefer to have a sound understanding of their studies rather than memorizing them by heart. They have known that such an understanding will only make them learn the studies in their long-term memory. Thus, clever students are given to studying their subject matter within the space of 24 hours after the lecture without fail. The reason why they have to study during this time is that their ability to understand may lessen bit by bit as long as their learning time takes. For a proper understanding of school lessons, they are inclined to practice insight learning, in which a student is able to study school subjects in depth. Therefore, some students are never hesitant to go and ask their teachers, classmates or even senior students the facts and figures of something that they have not yet understood well or at all.

The fact that students pass the exam with their eyes closed needs regular study, but together with frequent practice and continuous repetition of school lessons as much as they can, particularly for the matriculation examination. Quite frankly, simply regular study will be inadequate for intelligent students who hope to do well in the exams with remarkable achievements. Most of all, regular study can only give rise to a better understanding of school lessons than average. Students’ practice and repetition of school studies are more likely to depend on their learning rate. However, the learning rate is, students who are perfectly willing to pass the exam often revise all of their school subjects, namely, daily, weekly or sometimes monthly, just knowing that memory and forgetting always go hand in hand. School lessons are certain to come and go easily due to proactive or retroactive inhibition. Therefore, students do as much practice and repetition of school studies as needed for their exams. Needless to say, practice makes perfect.

It is natural that, as human beings, students cannot stay away from a variety of physical, mental and emotional states. Most high school students, especially those who will sit the matriculation examination, are off colour too often, especially due to stress from studies. At that time, what they should know is that physical health enables learning readiness to study subjects, join group discussions or carry out school activities heart and soul at all times. Academic high-flyers, therefore, take good care of their health so as not to postpone or inhibit their daily learning routines. Like physical health, intelligent students know how to keep their mental and emotional well-being pretty well. The commonest mental or emotional state occurring in students’ minds is nothing but test anxiety or exam nerves, which means that they are frightened of taking exams. Nevertheless, some students are apt to prepare for the exam by studying hard and enough, having little anxiety or no intense anxiety over exam results. For them, several emotional states due to family or friendship cases can be neglected very quickly.

After all, students who will pass the exam beyond doubt usually have a lifelong ambition; it may be a doctor, an engineer, a teacher or something else. This ambition will prepare the ground for the future step with which they desire to walk through their whole life. It is an undeniable fact that too many studies can make most students exhausted or sometimes depressed to the extent that they do not want to go to school anymore. Despite this, their life ambition enables them to keep hard work and diligence, stamina in particular, which is the physical or mental strength to do something difficult for a long period, in their school studies. As to preparation for the exam, many students do not have the stamina to conduct studies throughout the entire school year. Still, bright students always take a lot of stamina for an academic year on end to arrive at their learning target. Last but not least, students who will do well in the exam without a doubt have a positive attitude towards exams, mainly `This too will pass´.

GNLM

As dawn broke across Myanmar on 27 July, students, families, and teachers gathered at schools and examination centres to receive the long-awaited results of the 2025 matriculation examination. Out of 207,898 candidates, 99,924 passed, yielding a national pass rate of 48.06 per cent. For many, the day brought celebration. For others, quiet disappointment. But beneath the surface of these numbers lies a deeper story — one that challenges how we define success and how we support those who fall outside its conventional frame.

As dawn broke across Myanmar on 27 July, students, families, and teachers gathered at schools and examination centres to receive the long-awaited results of the 2025 matriculation examination. Out of 207,898 candidates, 99,924 passed, yielding a national pass rate of 48.06 per cent. For many, the day brought celebration. For others, quiet disappointment. But beneath the surface of these numbers lies a deeper story — one that challenges how we define success and how we support those who fall outside its conventional frame.

In a society where achievement is often measured by grades and distinctions, the term “non-achiever” has become a label too easily applied, and too rarely questioned. Yet for every student whose name didn’t appear on the pass list, there exists a reservoir of potential, unseen, unmeasured, and often misunderstood.

This is where mentors and life coaches become vital. They are not architects of ambition, but gardeners of growth. Their role is not to push youth towards a singular goal, but to help them discover their own compass. For those who didn’t pass, the options are not closed; they are simply different. Vocational training, creative arts, community engagement, and entrepreneurial exploration offer paths where academic metrics may have failed to capture true capability.

Mentors help reframe the narrative. “Underperforming” becomes “underexplored.” Life coaches guide young people through emotional terrain, teaching resilience not as endurance, but as graceful recovery. They celebrate micro-achievements: the courage to try again, the strength to speak up, the wisdom to reflect. These are not lesser victories; they are the foundations of lifelong growth.

In earthquake-affected regions like Mandalay, where students faced additional challenges and retook exams in June, the resilience shown was extraordinary. Even in adversity, distinctions were earned, and spirits remained unbroken. This is a reminder that achievement is not always loud; it can be quiet, persistent, and deeply personal.

As Myanmar reflects on this year’s results, let us also reflect on the stories behind the scores. Let us honour the mentors who walk beside the youth, not ahead of them. And let us remember that the garden beyond the gate is vast, filled with paths that may not lead to trophies, but to transformation.

As dawn broke across Myanmar on 27 July, students, families, and teachers gathered at schools and examination centres to receive the long-awaited results of the 2025 matriculation examination. Out of 207,898 candidates, 99,924 passed, yielding a national pass rate of 48.06 per cent. For many, the day brought celebration. For others, quiet disappointment. But beneath the surface of these numbers lies a deeper story — one that challenges how we define success and how we support those who fall outside its conventional frame.

In a society where achievement is often measured by grades and distinctions, the term “non-achiever” has become a label too easily applied, and too rarely questioned. Yet for every student whose name didn’t appear on the pass list, there exists a reservoir of potential, unseen, unmeasured, and often misunderstood.

This is where mentors and life coaches become vital. They are not architects of ambition, but gardeners of growth. Their role is not to push youth towards a singular goal, but to help them discover their own compass. For those who didn’t pass, the options are not closed; they are simply different. Vocational training, creative arts, community engagement, and entrepreneurial exploration offer paths where academic metrics may have failed to capture true capability.

Mentors help reframe the narrative. “Underperforming” becomes “underexplored.” Life coaches guide young people through emotional terrain, teaching resilience not as endurance, but as graceful recovery. They celebrate micro-achievements: the courage to try again, the strength to speak up, the wisdom to reflect. These are not lesser victories; they are the foundations of lifelong growth.

In earthquake-affected regions like Mandalay, where students faced additional challenges and retook exams in June, the resilience shown was extraordinary. Even in adversity, distinctions were earned, and spirits remained unbroken. This is a reminder that achievement is not always loud; it can be quiet, persistent, and deeply personal.

As Myanmar reflects on this year’s results, let us also reflect on the stories behind the scores. Let us honour the mentors who walk beside the youth, not ahead of them. And let us remember that the garden beyond the gate is vast, filled with paths that may not lead to trophies, but to transformation.

The results of Grade XII (Matriculation) 2025 exams have now been issued.

This article is about the Matriculation exams format and modes of exam since 1964. It is mainly past-oriented. The focus of this article is on the method of entry to Universities and Colleges for those who passed the Matriculation examination and how the marks/grades and other methods were used in the past six decades. It is partly descriptive but is interspersed with commentaries.

The results of Grade XII (Matriculation) 2025 exams have now been issued.

This article is about the Matriculation exams format and modes of exam since 1964. It is mainly past-oriented. The focus of this article is on the method of entry to Universities and Colleges for those who passed the Matriculation examination and how the marks/grades and other methods were used in the past six decades. It is partly descriptive but is interspersed with commentaries.

The ILA System (Intelligence Level Aggregate) used for entrance to Universities for Matriculants from 1964 to 1968

The then-revolutionary government introduced and implemented the new education system starting in the year 1964. The ‘inaugural ILA system’ is also implemented for matriculates who matriculated that year.

In 1964, both in the arts and science combination, the students had to study five subjects for the Matric exams. In the science combination, the compulsory subjects were Burmese, English, Mathematics, Chemistry, and Physics. In the arts combination or arts/science mixed combination, they were Burmese, English, Geography, History, Mathematics or maybe if not mathematics, then such subjects as matriculation level statistics or economics or Pali language.

Burmese, English and Mathematics were compulsory for students in the science combination. Perhaps at least some of the students in the arts combination took Mathematics as a subject.

Though very rare, it is not that difficult to obtain 100 per cent marks, especially in the Mathematics paper. For the papers in Chemistry and Physics subjects, it is not that uncommon for candidates to obtain over 90 per cent marks in their exams. It would be well-nigh impossible to obtain 100 per cent in the Burmese and English papers. Indeed, one can say with confidence that in the past 60 years, i.e., those who matriculated from the years 1964 to 2025, there may not be a single candidate who obtained 100 per cent, nay even 95 per cent marks in both Burmese and English papers. In the past 60 years, there could, at the very least, be several hundred matriculates who obtained 100 per cent in mathematics and well over 90 per cent in the chemistry and physics matriculation papers. For the arts combinations, those who obtained say 90 per cent or above in the subjects of geography and history would be very rare; much rarer in any case than those who obtained 90 per cent or above in the subjects of chemistry and physics in the science combination.

The ILA system allocated a maximum of 20 marks to each of the five subjects. For the Mathematics papers, since 100 per cent is not that rare, it can be roughly estimated that only if a matriculant obtains 90 per cent or above, that student would get an ILA of 20 (maximum) points. It is unrealistic, not to say unfair, for a matriculant to obtain 90 per cent or more in the compulsory Burmese and English papers to get the full 20 points. A 1966 matriculant, now a medical doctor, told me that he obtained 66 marks in the matriculation Burmese paper, and he obtained 18 ILA points for the Burmese paper. For those who got 66 marks in the science subjects of chemistry, mathematics and physics, they certainly would not get 18 points but perhaps only 14 to 16 points. The same medical doctor also told me that he obtained 45 per cent in the English paper and obtained 12 ILA points.

Moreover, I know of one person who passed the Matric exam in 1964 from the Arts combination (perhaps he took Mathematics as a subject) and got admitted to the then Institute of Medicine, Mandalay. He stated that he was not taught basic science subjects like chemistry, physics in high school. He was formally taught those science subjects only when he was in the first year of the Medical course.

From the ILA to the ‘average marks’ system, 1969 to 1978

The ILA system was a reasonable and fair system where there was levelling or calibrating, so to speak, of marks in different matric subjects. As stated above, the maximum scores for arts (Burmese, English, Geography, History) were and are significantly less than those of the science subjects (Mathematics, Chemistry, Physics and later Biology). But the ILA system, after being implemented for five years, came to an end starting with the year 1969.

There may be a few reasons for this change. One is that in the science combinations, there was an additional subject that the matriculation candidates had to take. Most science students took the subject of Biology; fewer students took the subject of Geology. So, all students have to take six compulsory subjects (as contrasted to five in pre-1969 years).

Perhaps in the Arts combination, the students have to take Burmese, English (as in the science combination students). Mathematics may not be compulsory. But they too have to take six subjects. In addition to Mathematics, other subjects would include History, Geography, Economics or Pali language post-1969.

The ILA system was practised for five years when there were only five compulsory subjects for matriculants to take. So, the allocation of up to 20 maximum points for each subject nicely averaged out and ‘round up’ to 100 per cent.

Post-1968 matriculates have to take six subjects. If the ILA system were to be continued to be implemented, the ILA points that could be allocated to each subject if it were to be implemented (it was not) would be around 16.16 maximum points for each subject. The number would be an awkward way to calculate ILA points. Moreover, with each passing year, the number of matriculation students increased. In addition to the anomaly for assigning ILA points to six subjects, the complexities and the sheer number of an increase in student numbers who matriculated would be the intricacies or constraints that could prevent from continuation of the practice of the ILA system post-1968.

The sole criterion for entrance into one’s choice of Universities and Colleges during those years from 1969 to 1976 was the total marks one obtained in the Matric exam. Notably, science combination matriculates can apply for Arts subjects like law, economics, psychology, philosophy and Burmese majors, etc. On the other hand, those who graduated from the Arts ‘stream’ in those years cannot take University courses in science subjects like medicine, engineering, chemistry major, botany major zoology major even if their marks should they be science students would make them eligible to take these subjects. This is in contrast to the ILA system, where a candidate who scores good marks in the Matric exam, mainly with Arts subjects, can take the course in medicine and also other science subjects.

I will briefly state about two matriculants whom I know of to illustrate or exemplify the anomalies of the ‘average marks’ system. In the year 1970, a few of my classmates and I in the 10th standard at the No 6 State High School, Mandalay, matriculated. In that year, the minimum marks needed to get into any of the three Institutes of Medicine were 416 marks out of 600. Ko Ba Shwin, a classmate, obtained 414 marks in the Matric exam. He obtained perhaps two distinctions in the science subjects. He was two marks short of getting into the medical course. His parents were not well-to-do, so they could not send him to Rangoon to take the engineering course at the Rangoon Institute of Technology (RIT) (as it was then called), which he was well-qualified to take if he were to apply. So, apparently, he put his second choice as a Mathematics major in his University application. When I met him in August 1970, his University admission results had just come out. He told me bemoaningly that he made a mistake in his Mathematics matriculation paper regarding ‘cosine’ (in perhaps the trigonometry or geometry section). He said ‘ … if only I did the cosine correctly ..’ (he would have been admitted to the medical course). I might add that he could have become a medical doctor too. Ko Ba Shwin graduated with a Maths major from the Mandalay Arts and Science University (MASU). The last time I heard about him was from a common classmate. He told me that Ko Ba Shwin was working in a Bank in Mandalay. He must have retired by now.

Over ten years later, in the 1980s, a person that I know passed the Matriculation exam with a few distinctions. The person applied for the medical course. The marks that the person obtained were such that ‘they’ just made it to the medical course. Just as Ko Ba Shwin about ten years earlier missed getting into the medical course by two marks, they’ just managed to get into the medical course by meeting the minimum marks. ‘They’ have become a prosperous medical doctor. So, it is sheer luck or chance (or in the case of Ko Ba Shwin, the mistakes in the ‘cosine’ calculations) that determines one’s professional career path.

These are only two examples that I know of, which indicates the anomaly of the ‘average mark’ system determining one’s professional career. If Ko Ba Shwin’s (or maybe several hundred, even a few thousand others like him) application for University admissions were to be decided by the defunct (since 1969) ILA system, he might get admitted to the medical course. But that was and is ‘iffy history’. What is not iffy history, and arguably what is fairer in determining admission to Universities and Colleges, was the ‘Regional College’ system.

Regional College system (1976/77 to 1980-81)

The Burma Socialist Programme Party government faced quite a few student-led demonstrations from 1974 to 1976. Partly due to this, the University students would ‘spread out’ and the then government implemented the Regional College system. Students after matriculation had to study for two years at Regional Colleges in their region. For example, in the Rangoon division (as it then was called), there were two Regional Colleges. The admission to Universities and Colleges during their Regional College years was determined not by the marks obtained in the Matric exam alone. It was determined by the average cumulative marks obtained (1) in the Matric exam, (2) first year marks at Regional Colleges (3) second year marks at Regional Colleges are combined. The cumulative marks in each course obtained are divided by three. Say, the Matriculation marks are 420 marks out of 600. Since there are six subjects in the Matric exam, the average marks obtained for the Matric would be 70 marks. Likewise, the marks obtained in first- and second-year regional colleges are added to the score, and average marks are calculated. A person who matriculated in 1980 told me that he obtained a cumulative average of 64 marks for this trifecta (so to speak) assessment. He applied for Civil Engineering at the Rangoon Institute of Technology but missed it by (0.4) marks (less than half a mark). He got his second-choice geology major at Rangoon Arts and Science University and graduated from it.

I understand that the Chief Editor of The Global New Light of Myanmar had gone through this trifecta assessment and made his first choice as an English major at Rangoon Arts and Science University. Perhaps @editor might wish to write about his Regional College experiences in his usual Wednesday columns.

In the not-so-humble opinion of yours truly, the ILA system and the Regional College system practised in the days of yore are fairer, less anomalous and, shall we say – at times less arbitrary – than the system of what courses a matriculate can take is based solely on marks obtained or failed to obtain in the candidate’s matriculation exams.

Back to average marks again 1982 to 1986, Matriculation exams

The ILA system lasted from 1964 to 1968, about five years. The Regional College system lasted from 1976 to 1981, also about five years. From 1982 to 1986, the system reverted to ‘average marks as sole determinant’ to decide what courses students can take. But before that, to use metaphorically and somewhat mockingly, even – dare I say it – contemptuously, the ‘marriage’ and ‘divorce’ of arts and sciences subjects in the Matriculation or pre-Matriculation years have taken place five times between 1968 and the year 2000. From 1970 to 1978, there was a division of arts and science subjects in the Matriculation exams.

In May 1974, an article appeared in The Working People’s Daily predecessor of The Global New Light of Myanmar. It said, in effect, that the arts and science division in high schools ‘should go’. That was the last sentence of the article. I have forgotten the name of the writer. So, the ‘divorce’ of arts and science subjects in the Matriculation exams stopped, starting in the year 1979. From 1979 to 1986, all matriculate students had to take the following arts/science combined subjects. (1) Burmese (2) English (3) Mathematics (4) Physics-Chemistry (5)Geography-Economics (6) History (The first five subjects are a three-hour exam, and History is a two-hour exam). Hence, the person whom I have mentioned above as ‘just’ reaching the medical course occurred in those years when arts and science were combined, but there were no more students studying at Regional Colleges.

This average marks system, when arts-science subjects were combined, lasted like the ILA system about five years

The ‘divorce’ of arts and science subjects in the pre-matriculation and matriculation years took place again starting from the 1986-87 academic year.

Arts and Science Division again: 1987 to 1991 Matric exams

Starting from the year 1987, lasting to 1991 (or) 1992 there is again a division of arts and science subjects in the Matriculation exams. The division began in the eighth standard. The government-sponsored exams took place. Based on the marks the eighth standard students obtained, they are either assigned to take the science combination or the arts combination in their 9th and 10th standards.

In the science stream (so to speak), the subjects are the compulsory subjects of Burmese, English, Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry and Biology.

There were two ‘sub-streams’ in the Arts combination, so to speak. Those who were allotted to the Arts stream starting from the 9th standard had a choice to choose apart from the compulsory Burmese and English papers either the Economics and Maths combination or the Optional Burmese (OB) and Additional English (AE) combinations. Here, I would state that those who are in the arts ‘sub-stream’ of economics and maths have to take both subjects. A student who passed the Matriculation exam in 1988 told me that as far as the Maths paper during those years was concerned, the science combination and arts combination students had to answer the same paper. However, for those who took the OB and AE combination, their ‘encounter’ with maths ended when they passed the eighth standard.

And whereas those Arts combination of maths-economics can apply to the then Institute of Economics, the OB and AE students could not since both maths and basic economics are necessary for University economics students.

The peculiarity of the system practised during the time of this ‘divorce’ of Arts/Science dichotomy is that once a student has matriculated from the Science stream, he or she could not take Arts subjects at all in University courses. Say a student from the science stream obtained a distinction in English language (75 per cent in the Matric exam), ‘they’ could not take an English major since they matriculated from the science stream. But a student who matriculated from the Arts stream, even if she or he obtained, say, 60 per cent in English or even 55 per cent, can enrol in an English major! Likewise, those who passed from the Science stream, even if their marks qualified them to major in law they could not take the subject. But those who matriculated from the Arts stream, whether their sub-speciality was Economics and Maths or Optional Burmese (OB) and Additional English (AE), could take a law major. Indeed, a matriculant who passed from the Arts stream with OB and AE specialization told me that among the roughly 300 students in the first-year law course that he attended, about 150 were from the maths-economics sub-speciality and 150 were from the OB-AE sub-speciality.

In 1991 or 1992, this division or divorce of Arts/Science subjects came to an end (again).

Incidentally, since 1991, there have been no offerings of the Additional English subject in the Matric exam. Concomitantly, very few students took the Optional Burmese course in recent years. I read in the newspapers that only a single student took the 2024 Grade XII exam with the Optional Burmese subject. I do not know whether or not Optional Burmese was offered as a subject in the 2025 Grade XII exams.

Recombination of Arts subjects and science subjects from the 1991 or 1992 Matric exams to the year 2000

For the fourth time since the year 1970, the division and combination of arts and science subjects took place again, starting from the year 1991 or 1992 and lasting until the year 2000. Since 1969, matriculants have had to take six subjects. Starting from 1991 or 1992, they had to take only five subjects, which were again a combination of arts and science subjects. They were (1) Burmese, (2) English, (3) Mathematics, (4) Biology-Chemistry-Physics (in one three-hour paper!) and (5) Economics-Geography-History in one three-hour paper! Hence, both science and arts subjects were offered in the Matric, unlike those matriculates in the 1987 to 1991/92 period.

From 2001 to current the three main choices of (full) Science/Science/Arts combined and Full Arts

In 2001, a new system came into force for matriculates.

Stream A: full science combination: (1) Myanmar Sar, (2) English, (3) Mathematics, (4) Physics, (5) Chemistry, (6) Biology

Stream B: Science/Arts Combination (1) Myanmar Sar, (2) English, (3) Mathematics, (4) Physics, (5) Chemistry, (6) Economics (Economics is considered an Arts subject) (Those who passed from this combination cannot apply for the medical courses since Biology is not in the curriculum. Contrast this with the 1964 to 1968 situation, where even those from the Arts combination, if their ILA points are high enough, can apply for the medical course.) It was only in 1969 that Biology became a compulsory or optional subject for those matriculation candidates in the science stream. I wrote ‘compulsory-optional’ since, although most students took biology as a sixth science subject, there was at least one alternative subject, Geology, which relatively few students took. I suppose that those who passed from the science combination who took Geology as a ‘compulsory-optional’ so long as they met the minimum marks required could take the medicine course. Not any more post-2001. Of course, both stream A and stream B can apply for the engineering course, but those from stream B cannot apply for the medical course.

Stream C: Full Arts combination (do not know whether this stream is available starting from 2025) Myanmar Sar, Seik Kyike Myanmar Sar (Optional Burmese), English, Geography, History, Economics.

Only a single candidate sat for the Optional Burmese paper in the March 2024 Grade XII exams.)

I would note that starting from 2024, students matriculate not at the tenth standard (now Grade X) but after Grade XII. Since only after students pass the Grade XII exams can they join Universities and Colleges, I wrote that Grade XII as ‘matriculation’ (since 2024).

Although there have been a few changes in the course curriculum of all subjects, both Arts and Sciences, the format (‘thank God’) or thank the concerned educational authorities, there have been no radical changes or reversals in relation to the science/arts division/combination since 2001.

As far as the writer can discern, no person has written either in the Myanmar or English language the gist of and commentary on the changes since 1964 regarding modes of joining Universities and Colleges. Some of the statements here regarding the changes, reversals, are from my memory, and there could be a few inaccuracies, but I trust they have not been substantially or substantively wrong.

I also interviewed or spoke with two persons who passed the Matric when the ILA system was in force (1964 to 1968), three persons when the Regional College system was in force (1976 to 1981), one person when the Arts/Science combination (without the Regional College system) was in force 1982 to 1986, two persons when the Arts/Science division was made (1987 to either 1990 or 1991), one person who passed in the when there was only five subjects in the Matric exam (1991 or 1992 to 2000) I thank the above persons for answering my phone queries.

As stated, this article is mainly past-oriented vis-à-vis Matric exams. I do not want to be ‘pompous’ by quoting philosopher George Santayana (16 December 1863-26 September 1952) and say ‘those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it’. As stated, after about 35 years of chopping and changing, especially as regards Arts/Science combination and division, stability has been achieved since 2001. That is indeed a positive thing, which almost a generation of matriculates were and are privileged (so to speak) to enjoy.

GNLM

The results of Grade XII (Matriculation) 2025 exams have now been issued.

This article is about the Matriculation exams format and modes of exam since 1964. It is mainly past-oriented. The focus of this article is on the method of entry to Universities and Colleges for those who passed the Matriculation examination and how the marks/grades and other methods were used in the past six decades. It is partly descriptive but is interspersed with commentaries.

The ILA System (Intelligence Level Aggregate) used for entrance to Universities for Matriculants from 1964 to 1968

The then-revolutionary government introduced and implemented the new education system starting in the year 1964. The ‘inaugural ILA system’ is also implemented for matriculates who matriculated that year.

In 1964, both in the arts and science combination, the students had to study five subjects for the Matric exams. In the science combination, the compulsory subjects were Burmese, English, Mathematics, Chemistry, and Physics. In the arts combination or arts/science mixed combination, they were Burmese, English, Geography, History, Mathematics or maybe if not mathematics, then such subjects as matriculation level statistics or economics or Pali language.

Burmese, English and Mathematics were compulsory for students in the science combination. Perhaps at least some of the students in the arts combination took Mathematics as a subject.

Though very rare, it is not that difficult to obtain 100 per cent marks, especially in the Mathematics paper. For the papers in Chemistry and Physics subjects, it is not that uncommon for candidates to obtain over 90 per cent marks in their exams. It would be well-nigh impossible to obtain 100 per cent in the Burmese and English papers. Indeed, one can say with confidence that in the past 60 years, i.e., those who matriculated from the years 1964 to 2025, there may not be a single candidate who obtained 100 per cent, nay even 95 per cent marks in both Burmese and English papers. In the past 60 years, there could, at the very least, be several hundred matriculates who obtained 100 per cent in mathematics and well over 90 per cent in the chemistry and physics matriculation papers. For the arts combinations, those who obtained say 90 per cent or above in the subjects of geography and history would be very rare; much rarer in any case than those who obtained 90 per cent or above in the subjects of chemistry and physics in the science combination.

The ILA system allocated a maximum of 20 marks to each of the five subjects. For the Mathematics papers, since 100 per cent is not that rare, it can be roughly estimated that only if a matriculant obtains 90 per cent or above, that student would get an ILA of 20 (maximum) points. It is unrealistic, not to say unfair, for a matriculant to obtain 90 per cent or more in the compulsory Burmese and English papers to get the full 20 points. A 1966 matriculant, now a medical doctor, told me that he obtained 66 marks in the matriculation Burmese paper, and he obtained 18 ILA points for the Burmese paper. For those who got 66 marks in the science subjects of chemistry, mathematics and physics, they certainly would not get 18 points but perhaps only 14 to 16 points. The same medical doctor also told me that he obtained 45 per cent in the English paper and obtained 12 ILA points.

Moreover, I know of one person who passed the Matric exam in 1964 from the Arts combination (perhaps he took Mathematics as a subject) and got admitted to the then Institute of Medicine, Mandalay. He stated that he was not taught basic science subjects like chemistry, physics in high school. He was formally taught those science subjects only when he was in the first year of the Medical course.

From the ILA to the ‘average marks’ system, 1969 to 1978

The ILA system was a reasonable and fair system where there was levelling or calibrating, so to speak, of marks in different matric subjects. As stated above, the maximum scores for arts (Burmese, English, Geography, History) were and are significantly less than those of the science subjects (Mathematics, Chemistry, Physics and later Biology). But the ILA system, after being implemented for five years, came to an end starting with the year 1969.

There may be a few reasons for this change. One is that in the science combinations, there was an additional subject that the matriculation candidates had to take. Most science students took the subject of Biology; fewer students took the subject of Geology. So, all students have to take six compulsory subjects (as contrasted to five in pre-1969 years).

Perhaps in the Arts combination, the students have to take Burmese, English (as in the science combination students). Mathematics may not be compulsory. But they too have to take six subjects. In addition to Mathematics, other subjects would include History, Geography, Economics or Pali language post-1969.

The ILA system was practised for five years when there were only five compulsory subjects for matriculants to take. So, the allocation of up to 20 maximum points for each subject nicely averaged out and ‘round up’ to 100 per cent.

Post-1968 matriculates have to take six subjects. If the ILA system were to be continued to be implemented, the ILA points that could be allocated to each subject if it were to be implemented (it was not) would be around 16.16 maximum points for each subject. The number would be an awkward way to calculate ILA points. Moreover, with each passing year, the number of matriculation students increased. In addition to the anomaly for assigning ILA points to six subjects, the complexities and the sheer number of an increase in student numbers who matriculated would be the intricacies or constraints that could prevent from continuation of the practice of the ILA system post-1968.

The sole criterion for entrance into one’s choice of Universities and Colleges during those years from 1969 to 1976 was the total marks one obtained in the Matric exam. Notably, science combination matriculates can apply for Arts subjects like law, economics, psychology, philosophy and Burmese majors, etc. On the other hand, those who graduated from the Arts ‘stream’ in those years cannot take University courses in science subjects like medicine, engineering, chemistry major, botany major zoology major even if their marks should they be science students would make them eligible to take these subjects. This is in contrast to the ILA system, where a candidate who scores good marks in the Matric exam, mainly with Arts subjects, can take the course in medicine and also other science subjects.

I will briefly state about two matriculants whom I know of to illustrate or exemplify the anomalies of the ‘average marks’ system. In the year 1970, a few of my classmates and I in the 10th standard at the No 6 State High School, Mandalay, matriculated. In that year, the minimum marks needed to get into any of the three Institutes of Medicine were 416 marks out of 600. Ko Ba Shwin, a classmate, obtained 414 marks in the Matric exam. He obtained perhaps two distinctions in the science subjects. He was two marks short of getting into the medical course. His parents were not well-to-do, so they could not send him to Rangoon to take the engineering course at the Rangoon Institute of Technology (RIT) (as it was then called), which he was well-qualified to take if he were to apply. So, apparently, he put his second choice as a Mathematics major in his University application. When I met him in August 1970, his University admission results had just come out. He told me bemoaningly that he made a mistake in his Mathematics matriculation paper regarding ‘cosine’ (in perhaps the trigonometry or geometry section). He said ‘ … if only I did the cosine correctly ..’ (he would have been admitted to the medical course). I might add that he could have become a medical doctor too. Ko Ba Shwin graduated with a Maths major from the Mandalay Arts and Science University (MASU). The last time I heard about him was from a common classmate. He told me that Ko Ba Shwin was working in a Bank in Mandalay. He must have retired by now.

Over ten years later, in the 1980s, a person that I know passed the Matriculation exam with a few distinctions. The person applied for the medical course. The marks that the person obtained were such that ‘they’ just made it to the medical course. Just as Ko Ba Shwin about ten years earlier missed getting into the medical course by two marks, they’ just managed to get into the medical course by meeting the minimum marks. ‘They’ have become a prosperous medical doctor. So, it is sheer luck or chance (or in the case of Ko Ba Shwin, the mistakes in the ‘cosine’ calculations) that determines one’s professional career path.

These are only two examples that I know of, which indicates the anomaly of the ‘average mark’ system determining one’s professional career. If Ko Ba Shwin’s (or maybe several hundred, even a few thousand others like him) application for University admissions were to be decided by the defunct (since 1969) ILA system, he might get admitted to the medical course. But that was and is ‘iffy history’. What is not iffy history, and arguably what is fairer in determining admission to Universities and Colleges, was the ‘Regional College’ system.

Regional College system (1976/77 to 1980-81)

The Burma Socialist Programme Party government faced quite a few student-led demonstrations from 1974 to 1976. Partly due to this, the University students would ‘spread out’ and the then government implemented the Regional College system. Students after matriculation had to study for two years at Regional Colleges in their region. For example, in the Rangoon division (as it then was called), there were two Regional Colleges. The admission to Universities and Colleges during their Regional College years was determined not by the marks obtained in the Matric exam alone. It was determined by the average cumulative marks obtained (1) in the Matric exam, (2) first year marks at Regional Colleges (3) second year marks at Regional Colleges are combined. The cumulative marks in each course obtained are divided by three. Say, the Matriculation marks are 420 marks out of 600. Since there are six subjects in the Matric exam, the average marks obtained for the Matric would be 70 marks. Likewise, the marks obtained in first- and second-year regional colleges are added to the score, and average marks are calculated. A person who matriculated in 1980 told me that he obtained a cumulative average of 64 marks for this trifecta (so to speak) assessment. He applied for Civil Engineering at the Rangoon Institute of Technology but missed it by (0.4) marks (less than half a mark). He got his second-choice geology major at Rangoon Arts and Science University and graduated from it.

I understand that the Chief Editor of The Global New Light of Myanmar had gone through this trifecta assessment and made his first choice as an English major at Rangoon Arts and Science University. Perhaps @editor might wish to write about his Regional College experiences in his usual Wednesday columns.

In the not-so-humble opinion of yours truly, the ILA system and the Regional College system practised in the days of yore are fairer, less anomalous and, shall we say – at times less arbitrary – than the system of what courses a matriculate can take is based solely on marks obtained or failed to obtain in the candidate’s matriculation exams.

Back to average marks again 1982 to 1986, Matriculation exams

The ILA system lasted from 1964 to 1968, about five years. The Regional College system lasted from 1976 to 1981, also about five years. From 1982 to 1986, the system reverted to ‘average marks as sole determinant’ to decide what courses students can take. But before that, to use metaphorically and somewhat mockingly, even – dare I say it – contemptuously, the ‘marriage’ and ‘divorce’ of arts and sciences subjects in the Matriculation or pre-Matriculation years have taken place five times between 1968 and the year 2000. From 1970 to 1978, there was a division of arts and science subjects in the Matriculation exams.

In May 1974, an article appeared in The Working People’s Daily predecessor of The Global New Light of Myanmar. It said, in effect, that the arts and science division in high schools ‘should go’. That was the last sentence of the article. I have forgotten the name of the writer. So, the ‘divorce’ of arts and science subjects in the Matriculation exams stopped, starting in the year 1979. From 1979 to 1986, all matriculate students had to take the following arts/science combined subjects. (1) Burmese (2) English (3) Mathematics (4) Physics-Chemistry (5)Geography-Economics (6) History (The first five subjects are a three-hour exam, and History is a two-hour exam). Hence, the person whom I have mentioned above as ‘just’ reaching the medical course occurred in those years when arts and science were combined, but there were no more students studying at Regional Colleges.

This average marks system, when arts-science subjects were combined, lasted like the ILA system about five years

The ‘divorce’ of arts and science subjects in the pre-matriculation and matriculation years took place again starting from the 1986-87 academic year.

Arts and Science Division again: 1987 to 1991 Matric exams

Starting from the year 1987, lasting to 1991 (or) 1992 there is again a division of arts and science subjects in the Matriculation exams. The division began in the eighth standard. The government-sponsored exams took place. Based on the marks the eighth standard students obtained, they are either assigned to take the science combination or the arts combination in their 9th and 10th standards.

In the science stream (so to speak), the subjects are the compulsory subjects of Burmese, English, Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry and Biology.

There were two ‘sub-streams’ in the Arts combination, so to speak. Those who were allotted to the Arts stream starting from the 9th standard had a choice to choose apart from the compulsory Burmese and English papers either the Economics and Maths combination or the Optional Burmese (OB) and Additional English (AE) combinations. Here, I would state that those who are in the arts ‘sub-stream’ of economics and maths have to take both subjects. A student who passed the Matriculation exam in 1988 told me that as far as the Maths paper during those years was concerned, the science combination and arts combination students had to answer the same paper. However, for those who took the OB and AE combination, their ‘encounter’ with maths ended when they passed the eighth standard.

And whereas those Arts combination of maths-economics can apply to the then Institute of Economics, the OB and AE students could not since both maths and basic economics are necessary for University economics students.

The peculiarity of the system practised during the time of this ‘divorce’ of Arts/Science dichotomy is that once a student has matriculated from the Science stream, he or she could not take Arts subjects at all in University courses. Say a student from the science stream obtained a distinction in English language (75 per cent in the Matric exam), ‘they’ could not take an English major since they matriculated from the science stream. But a student who matriculated from the Arts stream, even if she or he obtained, say, 60 per cent in English or even 55 per cent, can enrol in an English major! Likewise, those who passed from the Science stream, even if their marks qualified them to major in law they could not take the subject. But those who matriculated from the Arts stream, whether their sub-speciality was Economics and Maths or Optional Burmese (OB) and Additional English (AE), could take a law major. Indeed, a matriculant who passed from the Arts stream with OB and AE specialization told me that among the roughly 300 students in the first-year law course that he attended, about 150 were from the maths-economics sub-speciality and 150 were from the OB-AE sub-speciality.

In 1991 or 1992, this division or divorce of Arts/Science subjects came to an end (again).

Incidentally, since 1991, there have been no offerings of the Additional English subject in the Matric exam. Concomitantly, very few students took the Optional Burmese course in recent years. I read in the newspapers that only a single student took the 2024 Grade XII exam with the Optional Burmese subject. I do not know whether or not Optional Burmese was offered as a subject in the 2025 Grade XII exams.

Recombination of Arts subjects and science subjects from the 1991 or 1992 Matric exams to the year 2000

For the fourth time since the year 1970, the division and combination of arts and science subjects took place again, starting from the year 1991 or 1992 and lasting until the year 2000. Since 1969, matriculants have had to take six subjects. Starting from 1991 or 1992, they had to take only five subjects, which were again a combination of arts and science subjects. They were (1) Burmese, (2) English, (3) Mathematics, (4) Biology-Chemistry-Physics (in one three-hour paper!) and (5) Economics-Geography-History in one three-hour paper! Hence, both science and arts subjects were offered in the Matric, unlike those matriculates in the 1987 to 1991/92 period.

From 2001 to current the three main choices of (full) Science/Science/Arts combined and Full Arts

In 2001, a new system came into force for matriculates.

Stream A: full science combination: (1) Myanmar Sar, (2) English, (3) Mathematics, (4) Physics, (5) Chemistry, (6) Biology

Stream B: Science/Arts Combination (1) Myanmar Sar, (2) English, (3) Mathematics, (4) Physics, (5) Chemistry, (6) Economics (Economics is considered an Arts subject) (Those who passed from this combination cannot apply for the medical courses since Biology is not in the curriculum. Contrast this with the 1964 to 1968 situation, where even those from the Arts combination, if their ILA points are high enough, can apply for the medical course.) It was only in 1969 that Biology became a compulsory or optional subject for those matriculation candidates in the science stream. I wrote ‘compulsory-optional’ since, although most students took biology as a sixth science subject, there was at least one alternative subject, Geology, which relatively few students took. I suppose that those who passed from the science combination who took Geology as a ‘compulsory-optional’ so long as they met the minimum marks required could take the medicine course. Not any more post-2001. Of course, both stream A and stream B can apply for the engineering course, but those from stream B cannot apply for the medical course.

Stream C: Full Arts combination (do not know whether this stream is available starting from 2025) Myanmar Sar, Seik Kyike Myanmar Sar (Optional Burmese), English, Geography, History, Economics.

Only a single candidate sat for the Optional Burmese paper in the March 2024 Grade XII exams.)

I would note that starting from 2024, students matriculate not at the tenth standard (now Grade X) but after Grade XII. Since only after students pass the Grade XII exams can they join Universities and Colleges, I wrote that Grade XII as ‘matriculation’ (since 2024).

Although there have been a few changes in the course curriculum of all subjects, both Arts and Sciences, the format (‘thank God’) or thank the concerned educational authorities, there have been no radical changes or reversals in relation to the science/arts division/combination since 2001.

As far as the writer can discern, no person has written either in the Myanmar or English language the gist of and commentary on the changes since 1964 regarding modes of joining Universities and Colleges. Some of the statements here regarding the changes, reversals, are from my memory, and there could be a few inaccuracies, but I trust they have not been substantially or substantively wrong.

I also interviewed or spoke with two persons who passed the Matric when the ILA system was in force (1964 to 1968), three persons when the Regional College system was in force (1976 to 1981), one person when the Arts/Science combination (without the Regional College system) was in force 1982 to 1986, two persons when the Arts/Science division was made (1987 to either 1990 or 1991), one person who passed in the when there was only five subjects in the Matric exam (1991 or 1992 to 2000) I thank the above persons for answering my phone queries.

As stated, this article is mainly past-oriented vis-à-vis Matric exams. I do not want to be ‘pompous’ by quoting philosopher George Santayana (16 December 1863-26 September 1952) and say ‘those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it’. As stated, after about 35 years of chopping and changing, especially as regards Arts/Science combination and division, stability has been achieved since 2001. That is indeed a positive thing, which almost a generation of matriculates were and are privileged (so to speak) to enjoy.

GNLM

What punctuation taught me about language, clarity, and the rhythm of thought

What punctuation taught me about language, clarity, and the rhythm of thought

Punctuation isn’t just decoration; it’s choreography. A well-placed exclamation mark can jolt readers to attention, while a modest full stop restores order. In this article, I navigate the fine line between clarity and chaos, revealing how the tiniest typographic symbols – dots, dashes, and squiggles – shape our thoughts, steer our tone, and even betray our intentions. Whether you’re whispering with ellipses or shouting with CAPS and exclamations, English punctuation is a drama worth decoding. And yes… things might get silly.

Punctuation Across the Page: Where Marks Make Meaning

Before dissecting dots and dashes, one must acknowledge their quiet dominion across genres. In the realm of essays, punctuation separates logic from rhetoric, guiding readers through layered argumentation. In articles, it tempos urgency and balances narrative with fact. Research papers rely on precision, where the placement of a colon or semicolon can distinguish methodology from interpretation. And in poetry, punctuation breathes, pauses, interrupts, and seduces; it’s a companion to rhythm, a silhouette to meaning.

Whether the voice is academic, journalistic, poetic, or reflective, punctuation remains the unseen composer. Without it, thought unravels into noise.

Punctuation and Its Purpose in English

In English writing, punctuation marks serve several important purposes:

(a) To make meaning clear

(b) To convey emphasis or seriousness

(c) To prevent ambiguity or misinterpretation

(d) To reflect tone, pause, and rhythm as in spoken language

During my time at the News Agency of Burma (NAB) between 1990 and 1993, while working at the foreign news desk, I had the opportunity to attend journalism courses where these functions of punctuation were not only taught but practically demonstrated through translation exercises and editing assignments. These lessons became part of my editorial muscle memory, and what follows is a brief but structured guide – refreshed in light of modern reference texts such as the Translator’s Reference (Seikku Cho Cho, June 2008).

1. Comma (,)

(a) Separates items in a list:

men, women, and children ran for cover.

(b) Sets off adverbial phrases placed before the main clause:

When they found the enemy had retreated, they occupied the town.

(c) Separates parenthetical elements and appositive phrases:

They visited Bagan, the famous historical site.

(d) Introduces or follows direct speech:

The delegate replied, “That is correct.”

(e) Resolves ambiguity:

To Nyi Nyi, Ko Ko is special.

(Without the comma, the meaning could shift.)

(f) Groups large numbers for readability:

100,000

(Note: Do not use commas for four-digit numbers, years, or address numbers – e.g., 1993, 4321, 1234 Pyi Lan.)

(g) Separates names from titles or qualifications:

Dr Ko Ko, FRCS

(h) Distinguishes city names from township or regional names:

Intagaw, Bago Township

Back in our newsroom at NAB, a misplaced comma could sometimes change the nuance of a foreign policy headline. Our instructor once joked that punctuation, like diplomacy, is all about timing, placement, and tone.

2. Semicolon (;)

(a) Links independent clauses without a conjunction:

Some positions were occupied; some were not.

(b) Connects clauses using conjunctive adverbs such as furthermore, consequently, however:

Speeding is illegal; furthermore, it is dangerous.

(c) Separates complex list items containing internal commas:

The search is for people who can think creatively, who can think for themselves, people who can work on their own ideas, and who can express themselves clearly.

3. Colon (:)

(a) Expands, explains, or clarifies what comes before:

The building was poorly designed: it lacked both function and unity.

(b) Focuses attention on a key word or phrase:

There is only one goal: freedom.

(c) Introduces a list:

Three countries were represented: China, Thailand, and Myanmar.

(d) Separates hours from minutes in time expressions:

8:30 am

4. Full Stop/Period (.)

(a) Ends a complete sentence.