“World Meditation Day” is observed on 21 December each year, a date declared by the United Nations Assembly to promote awareness of meditation and its benefits for mental and physical well-being.

“World Meditation Day” is observed on 21 December each year, a date declared by the United Nations Assembly to promote awareness of meditation and its benefits for mental and physical well-being.

Since my life of public service as an editor to chief editor, I learned and practised daily with the insight meditation of the Theravada Buddhism because of knowing how to escape from suffering, old age, sickness and death. (Anicca= အနိစ္စ “Anatta”= အနတ္တ I often went to the insight-meditation centre of “Ledi Sayadaw”, “Mogok Sayadaw”, “Mahasi Sayadaw” and “Sayagyi U Ba Khin” in Yangon.

Theravada Buddhism teaches two kinds of Meditation:

(1) Samatha-bhavana(သမထဘာ၀နာ) = Concentration Meditation

(2) Vipassana-bhavana (ဝိပဿနာဘာဝနာ) = Insight Meditation

Samatha-bharvana aims at gaining concentration or one-pointedness of Mind, and Vippasana-bhavana enables the practitioner to purify their Minds and acquire an insight into the real nature of all phenomena.

Technically speaking, concentration is the basis of insight. It is developed by fixing one’s mind on a chaser object, say, a Buddha image, candlelight, a circular disc pointed in a particular colour or on breathing. Buddhist commentaries elaborate on forty varieties of such meditation objects, but the list may be extended indefinitely.

Insight meditation, on the other hand, is practised through the application of one’s mind to the nature of things to be constantly mindful of one’s physical and mental activities, so one may be able to penetrate deeply into the real nature of existence and do away with own mental impurities. In short, insight meditation is the direct purification method to cleanse one’s mind of evils.

Both concentration and insight meditation can be developed side by side, and the development of one helps in the cultivation of the other. But ultimately, it is only insight meditation that, when perfected, leads man to the highest wisdom and cleanses his mind of all impurities, once and for all.

Both kinds of meditation can be practised and applied in our daily lives. Both are of immense benefit to traction. Of all the many aspects of the Buddhist religion, meditation occupies a very important place of interest, especially in the west countries. In several Asian nations, like Myanmar, Japan, Thailand and Sri Lanka, where Buddhism is still very much a living force, it enjoys a long and uninterrupted tradition, receiving in more recent years even wider recognition among the populace.

As science and technology become increasingly developed, people have more and more cause to realize the relevance and significance of Buddhist meditation to life.

Meditation is a means of mental development. In Buddhism, the mind is the most important component of the entire human entity. Meditation is the training of the mind, and because the mind is the most important factor that manipulates and controls our actions and speech, the practice of meditation can bring infinite benefits to us in life. Below are the best advantages of meditation:

(1) Meditation helps to calm the mind and get it better organized.

(2) Meditation strengthens our willpower and enables us to face all problems

and difficulties with confidence.

(3) Meditation makes us think positively.

(4) It improves our efficiency at work by helping us to concentrate better and by sharpening our mental faculties.

(5) It frees us from worries, restless ness, etc.

(6) Meditation increases our mental health and therefore has a positive effect, to a large extent, on our physical health.

(7) It cleanses our mind of defilements.

(Kilesa = ကိလေသာ)

Let me roughly describe the “Defilement” as follows, according to the noble Theravada Buddhism.

The “Defilement” means mind-defiling factor, impurity. There are ten kinds of mind-defiling factors have been enumerated as:

(a) Greed (Lobha = လောဘ = လိုချင်တက်မက်ခြင်း)

(b) Hatred (Dosa = ဒေါသ = အမျက်ထွက်ခြင်း)

(c) Bewildment (Moha = မောဟ = တွေဝေခြင်း)

(d) Conceit (Mona = မာန = ထောင်လွှားခြင်း)

(e) Doubt (Vicikiecha = ဝိစိကိစ္ဆာ= ယုံမှားခြင်း၊ မဆုံးဖြတ်ခြင်ခြင်း)

(f) Mental Torpor = (Htina =ထိန = ထိုင်းမှိုင်းခြင်း)

(g) Restlessness = (Uddhacc = ဥဒ္ဒစ္စ = မတည်ငြိမ်ခြင်း၊ ပျံ့လွင့်ခြင်း)

(h) Shamelessness = (To do evil = အဟိရိက = Aheika= မကောင်းမပြုလုပ်ရမည်ကိုမရှက်ခြင်း)

(i) Not fearing to evil = (Anottappa = မကောင်းမပြုရမည်ကိုမကြောက်မ့ခြင်း)

Because of attaching firmly, the “Defilement” (Kilasa = ကိလေသာ) men and women cannot escape from “suffering” (ဒုက္ခ) or Sansayar (သံသရာ) or life=circle (ဘဝသံသရာ).

(8) Meditation creates in us virtuous qualities like kindness, inner peace, humbleness (as opposed to arrogance), a realistic attitude toward life, and prevents us from being influenced by such elements as passion, selfishness, hatred, jealousy or greed.

(9) An untrained person is often dominated by delusion (Avijja) and his own preconceptions, which prevent him from having proper insight into reality. Meditation helps to remove such disadvantages. Meditation should, however, be borne in mind that the degree of benefits a man can derive from such practice depends entirely on the degree of achievement he makes and on how far he can apply meditation to real life. Several factors are important for the success of the practice, for example, a proper atmosphere.

Spiritual preparedness, proper frame of mind, self-confidence, frequency and regularity in practice, and so on.

Mind fullness according to the discourse, four objects may be taken for the practice namely “Body”, “Sensation”, “Mind” and “Mental Objects” (1. Body = Insight Meditation of Body = ကာယာနုပဿနာသတိပဌာန်) (2. Sensation = Insight Meditation of Venda = ဝေဒနာနုပဿနာသတိပဌာန်) (3. Mind = Insight Meditation of Citta = စိနုပဿနာသတိပဌာန်) (4. Mental Objects = Insight Meditation of Dhamma = ဓမ္မာနုပဿနာသတိပဌာန်). Mindfulness is the key insight of meditation. When practising this type of meditation, one should endeavour to be mindful at all times of one’s activities, mental and physical. Mindfulness should be developed to such an extent that it becomes natural and automatic. When that stage is reached, one can be said to dwell constantly in mindfulness. This is the way to spiritual purification.

Because of regularly practising insight meditation. I often get many good advantages for my life. For example, I fell seriously with a disease called prostate cancer and heart disease, near death, three years ago. However, I fortunately recovered from chronic sickness on account of the good medical treatment and insight meditation. Now I serve daily as a member of the Eaindawya Pagoda trustee as a retired person. Besides with help of guidance from the famous experienced monks of insight meditation, I can explain a conversational demonstration in insight meditation, which is always held every Sunday evening at the Eaindawya Pagoda, Yangon. The Theravada Buddhists always believe in the method of liberation from desire. (Sufferings)

References:

(1) The Buddhamama Meditation Centre by Sayadaw Dr Phra Sunthorn Plaminsr, USA

(2) Dictionary of Buddhist Terms (Religious Affairs, Yangon, Myanmar)

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

“World Meditation Day” is observed on 21 December each year, a date declared by the United Nations Assembly to promote awareness of meditation and its benefits for mental and physical well-being.

Since my life of public service as an editor to chief editor, I learned and practised daily with the insight meditation of the Theravada Buddhism because of knowing how to escape from suffering, old age, sickness and death. (Anicca= အနိစ္စ “Anatta”= အနတ္တ I often went to the insight-meditation centre of “Ledi Sayadaw”, “Mogok Sayadaw”, “Mahasi Sayadaw” and “Sayagyi U Ba Khin” in Yangon.

Theravada Buddhism teaches two kinds of Meditation:

(1) Samatha-bhavana(သမထဘာ၀နာ) = Concentration Meditation

(2) Vipassana-bhavana (ဝိပဿနာဘာဝနာ) = Insight Meditation

Samatha-bharvana aims at gaining concentration or one-pointedness of Mind, and Vippasana-bhavana enables the practitioner to purify their Minds and acquire an insight into the real nature of all phenomena.

Technically speaking, concentration is the basis of insight. It is developed by fixing one’s mind on a chaser object, say, a Buddha image, candlelight, a circular disc pointed in a particular colour or on breathing. Buddhist commentaries elaborate on forty varieties of such meditation objects, but the list may be extended indefinitely.

Insight meditation, on the other hand, is practised through the application of one’s mind to the nature of things to be constantly mindful of one’s physical and mental activities, so one may be able to penetrate deeply into the real nature of existence and do away with own mental impurities. In short, insight meditation is the direct purification method to cleanse one’s mind of evils.

Both concentration and insight meditation can be developed side by side, and the development of one helps in the cultivation of the other. But ultimately, it is only insight meditation that, when perfected, leads man to the highest wisdom and cleanses his mind of all impurities, once and for all.

Both kinds of meditation can be practised and applied in our daily lives. Both are of immense benefit to traction. Of all the many aspects of the Buddhist religion, meditation occupies a very important place of interest, especially in the west countries. In several Asian nations, like Myanmar, Japan, Thailand and Sri Lanka, where Buddhism is still very much a living force, it enjoys a long and uninterrupted tradition, receiving in more recent years even wider recognition among the populace.

As science and technology become increasingly developed, people have more and more cause to realize the relevance and significance of Buddhist meditation to life.

Meditation is a means of mental development. In Buddhism, the mind is the most important component of the entire human entity. Meditation is the training of the mind, and because the mind is the most important factor that manipulates and controls our actions and speech, the practice of meditation can bring infinite benefits to us in life. Below are the best advantages of meditation:

(1) Meditation helps to calm the mind and get it better organized.

(2) Meditation strengthens our willpower and enables us to face all problems

and difficulties with confidence.

(3) Meditation makes us think positively.

(4) It improves our efficiency at work by helping us to concentrate better and by sharpening our mental faculties.

(5) It frees us from worries, restless ness, etc.

(6) Meditation increases our mental health and therefore has a positive effect, to a large extent, on our physical health.

(7) It cleanses our mind of defilements.

(Kilesa = ကိလေသာ)

Let me roughly describe the “Defilement” as follows, according to the noble Theravada Buddhism.

The “Defilement” means mind-defiling factor, impurity. There are ten kinds of mind-defiling factors have been enumerated as:

(a) Greed (Lobha = လောဘ = လိုချင်တက်မက်ခြင်း)

(b) Hatred (Dosa = ဒေါသ = အမျက်ထွက်ခြင်း)

(c) Bewildment (Moha = မောဟ = တွေဝေခြင်း)

(d) Conceit (Mona = မာန = ထောင်လွှားခြင်း)

(e) Doubt (Vicikiecha = ဝိစိကိစ္ဆာ= ယုံမှားခြင်း၊ မဆုံးဖြတ်ခြင်ခြင်း)

(f) Mental Torpor = (Htina =ထိန = ထိုင်းမှိုင်းခြင်း)

(g) Restlessness = (Uddhacc = ဥဒ္ဒစ္စ = မတည်ငြိမ်ခြင်း၊ ပျံ့လွင့်ခြင်း)

(h) Shamelessness = (To do evil = အဟိရိက = Aheika= မကောင်းမပြုလုပ်ရမည်ကိုမရှက်ခြင်း)

(i) Not fearing to evil = (Anottappa = မကောင်းမပြုရမည်ကိုမကြောက်မ့ခြင်း)

Because of attaching firmly, the “Defilement” (Kilasa = ကိလေသာ) men and women cannot escape from “suffering” (ဒုက္ခ) or Sansayar (သံသရာ) or life=circle (ဘဝသံသရာ).

(8) Meditation creates in us virtuous qualities like kindness, inner peace, humbleness (as opposed to arrogance), a realistic attitude toward life, and prevents us from being influenced by such elements as passion, selfishness, hatred, jealousy or greed.

(9) An untrained person is often dominated by delusion (Avijja) and his own preconceptions, which prevent him from having proper insight into reality. Meditation helps to remove such disadvantages. Meditation should, however, be borne in mind that the degree of benefits a man can derive from such practice depends entirely on the degree of achievement he makes and on how far he can apply meditation to real life. Several factors are important for the success of the practice, for example, a proper atmosphere.

Spiritual preparedness, proper frame of mind, self-confidence, frequency and regularity in practice, and so on.

Mind fullness according to the discourse, four objects may be taken for the practice namely “Body”, “Sensation”, “Mind” and “Mental Objects” (1. Body = Insight Meditation of Body = ကာယာနုပဿနာသတိပဌာန်) (2. Sensation = Insight Meditation of Venda = ဝေဒနာနုပဿနာသတိပဌာန်) (3. Mind = Insight Meditation of Citta = စိနုပဿနာသတိပဌာန်) (4. Mental Objects = Insight Meditation of Dhamma = ဓမ္မာနုပဿနာသတိပဌာန်). Mindfulness is the key insight of meditation. When practising this type of meditation, one should endeavour to be mindful at all times of one’s activities, mental and physical. Mindfulness should be developed to such an extent that it becomes natural and automatic. When that stage is reached, one can be said to dwell constantly in mindfulness. This is the way to spiritual purification.

Because of regularly practising insight meditation. I often get many good advantages for my life. For example, I fell seriously with a disease called prostate cancer and heart disease, near death, three years ago. However, I fortunately recovered from chronic sickness on account of the good medical treatment and insight meditation. Now I serve daily as a member of the Eaindawya Pagoda trustee as a retired person. Besides with help of guidance from the famous experienced monks of insight meditation, I can explain a conversational demonstration in insight meditation, which is always held every Sunday evening at the Eaindawya Pagoda, Yangon. The Theravada Buddhists always believe in the method of liberation from desire. (Sufferings)

References:

(1) The Buddhamama Meditation Centre by Sayadaw Dr Phra Sunthorn Plaminsr, USA

(2) Dictionary of Buddhist Terms (Religious Affairs, Yangon, Myanmar)

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

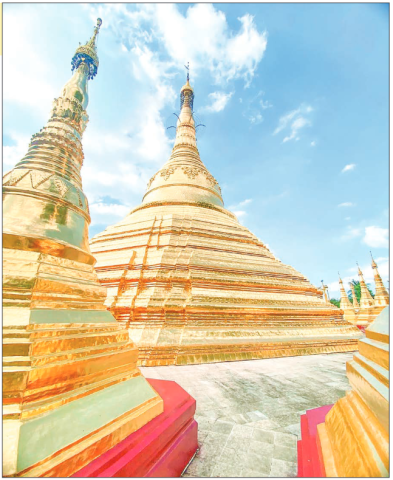

The Golden Rock: A Myanmar Marvel

The Golden Rock, also known as Kyaiktiyo Pagoda, is a breathtaking testament to the intersection of nature, faith, and human devotion. Perched precariously on the edge of a cliff in Myanmar's Mon State, this massive golden boulder is a sight to behold. Its allure draws thousands of visitors annually, from devout pilgrims seeking spiritual solace to curious travelers captivated by its unique beauty.

A Balancing Act of Nature and Legend

The Golden Rock: A Myanmar Marvel

The Golden Rock, also known as Kyaiktiyo Pagoda, is a breathtaking testament to the intersection of nature, faith, and human devotion. Perched precariously on the edge of a cliff in Myanmar's Mon State, this massive golden boulder is a sight to behold. Its allure draws thousands of visitors annually, from devout pilgrims seeking spiritual solace to curious travelers captivated by its unique beauty.

A Balancing Act of Nature and Legend

The Golden Rock defies gravity, seemingly poised on the brink of collapse. Legend has it that a single strand of the Buddha's hair miraculously keeps the boulder in place, a mystical explanation that adds to its sacred significance. Devotees have adorned the rock and the pagoda atop it with gold leaf, creating a dazzling spectacle that shimmers in the sunlight, especially at dawn and dusk.

A Pilgrimage of Faith

Visiting Kyaiktiyo Pagoda is a deeply meaningful pilgrimage for many Buddhists in Myanmar. Many undertake the arduous journey on foot, a testament to their unwavering faith. The path to the summit is lined with vendors selling food, drinks, and religious offerings, creating a vibrant atmosphere.

Religious festivals, particularly in November and December, see a surge of pilgrims. The air is filled with the chanting of monks, the flickering of candles, and the melodious chimes of prayer bells, creating an atmosphere of profound spirituality.

Planning for visit

The Golden Rock is located approximately 210 kilometers from Yangon. Reaching the summit typically involves a drive to the base camp at Kinpun, followed by a ride in an open-air truck or a challenging hike.

Comfortable shoes and ample water are essential, especially for those opting to hike. Accommodation options range from basic guesthouses to more comfortable hotels, catering to diverse needs.

A symbol of faith and resilience

The Golden Rock is more than just a geological wonder; it's a symbol of Myanmar's rich spiritual heritage and the enduring faith of its people. Whether you're drawn by the legend, the stunning vistas, or the profound spiritual atmosphere, a visit to Kyaiktiyo Pagoda is an unforgettable experience.

The Golden Rock: A legend in gold

The Golden Rock, a massive granite boulder covered in shimmering gold leaf, defies gravity by precariously balancing on the edge of a cliff. Legend has it that a single strand of Buddha's hair, enshrined within the pagoda atop the rock, miraculously keeps it in place. This sacred relic, gifted by the Buddha to a hermit and subsequently protected by his descendants, is believed to imbue the rock with its extraordinary position.

A pilgrimage of faith

For Buddhists, Kyaiktiyo Pagoda is a sacred site of immense spiritual significance. Pilgrims undertake arduous journeys to offer prayers, meditate, and apply gold leaf to the rock as an act of devotion. It is believed that visiting the Golden Rock at least once in a lifetime brings blessings and merits.

The site is particularly vibrant during Buddhist festivals, such as the Tazaungdaing Festival in November or December. Thousands of candles illuminate the pagoda, and the air resonates with the chants and prayers of devout pilgrims.

A legacy of endurance

Kyaiktiyo Pagoda has stood for over 2,500 years, a testament to both its enduring strength and the unwavering faith of its devotees. Despite weathering the elements, the rock remains intact, thanks to continuous maintenance and the ongoing contributions of pilgrims who add layers of gold leaf, symbolizing their spiritual connection to the site.

The name "Kyaiktiyo" itself holds significance. In the Mon language, "Kyaik" means "pagoda," "ti" means "hermit," and "yo" means "carry on the hermit's head." Thus, "Kyaiktiyo" translates to "pagoda upon a hermit's head."

Journey of discovery

Reaching the Golden Rock is an adventure. Visitors typically travel to the base camp at Kinpun and then ascend in open trucks along winding roads. From there, they can hike the remaining distance or hire a sedan chair carried by porters.

The journey offers breathtaking views of the surrounding hills, lush forests, and traditional Mon villages, providing an immersive experience into Myanmar's natural beauty and cultural heritage.

Kyaiktiyo Pagoda is more than just a tourist destination; it's a profound symbol of Myanmar's spiritual heritage. The golden glow of the rock at sunrise and sunset, combined with the serene mountain atmosphere, creates an unforgettable experience for all who visit. Whether drawn by its religious significance, its natural wonder, or the allure of its legend, the Golden Rock promises a journey of discovery and reflection. –

References

– kyaiktiyopagoda.org

– Go-Myanmar.com

– Global New Light of Myanmar

The Golden Rock: A Myanmar Marvel

The Golden Rock, also known as Kyaiktiyo Pagoda, is a breathtaking testament to the intersection of nature, faith, and human devotion. Perched precariously on the edge of a cliff in Myanmar's Mon State, this massive golden boulder is a sight to behold. Its allure draws thousands of visitors annually, from devout pilgrims seeking spiritual solace to curious travelers captivated by its unique beauty.

A Balancing Act of Nature and Legend

The Golden Rock defies gravity, seemingly poised on the brink of collapse. Legend has it that a single strand of the Buddha's hair miraculously keeps the boulder in place, a mystical explanation that adds to its sacred significance. Devotees have adorned the rock and the pagoda atop it with gold leaf, creating a dazzling spectacle that shimmers in the sunlight, especially at dawn and dusk.

A Pilgrimage of Faith

Visiting Kyaiktiyo Pagoda is a deeply meaningful pilgrimage for many Buddhists in Myanmar. Many undertake the arduous journey on foot, a testament to their unwavering faith. The path to the summit is lined with vendors selling food, drinks, and religious offerings, creating a vibrant atmosphere.

Religious festivals, particularly in November and December, see a surge of pilgrims. The air is filled with the chanting of monks, the flickering of candles, and the melodious chimes of prayer bells, creating an atmosphere of profound spirituality.

Planning for visit

The Golden Rock is located approximately 210 kilometers from Yangon. Reaching the summit typically involves a drive to the base camp at Kinpun, followed by a ride in an open-air truck or a challenging hike.

Comfortable shoes and ample water are essential, especially for those opting to hike. Accommodation options range from basic guesthouses to more comfortable hotels, catering to diverse needs.

A symbol of faith and resilience

The Golden Rock is more than just a geological wonder; it's a symbol of Myanmar's rich spiritual heritage and the enduring faith of its people. Whether you're drawn by the legend, the stunning vistas, or the profound spiritual atmosphere, a visit to Kyaiktiyo Pagoda is an unforgettable experience.

The Golden Rock: A legend in gold

The Golden Rock, a massive granite boulder covered in shimmering gold leaf, defies gravity by precariously balancing on the edge of a cliff. Legend has it that a single strand of Buddha's hair, enshrined within the pagoda atop the rock, miraculously keeps it in place. This sacred relic, gifted by the Buddha to a hermit and subsequently protected by his descendants, is believed to imbue the rock with its extraordinary position.

A pilgrimage of faith

For Buddhists, Kyaiktiyo Pagoda is a sacred site of immense spiritual significance. Pilgrims undertake arduous journeys to offer prayers, meditate, and apply gold leaf to the rock as an act of devotion. It is believed that visiting the Golden Rock at least once in a lifetime brings blessings and merits.

The site is particularly vibrant during Buddhist festivals, such as the Tazaungdaing Festival in November or December. Thousands of candles illuminate the pagoda, and the air resonates with the chants and prayers of devout pilgrims.

A legacy of endurance

Kyaiktiyo Pagoda has stood for over 2,500 years, a testament to both its enduring strength and the unwavering faith of its devotees. Despite weathering the elements, the rock remains intact, thanks to continuous maintenance and the ongoing contributions of pilgrims who add layers of gold leaf, symbolizing their spiritual connection to the site.

The name "Kyaiktiyo" itself holds significance. In the Mon language, "Kyaik" means "pagoda," "ti" means "hermit," and "yo" means "carry on the hermit's head." Thus, "Kyaiktiyo" translates to "pagoda upon a hermit's head."

Journey of discovery

Reaching the Golden Rock is an adventure. Visitors typically travel to the base camp at Kinpun and then ascend in open trucks along winding roads. From there, they can hike the remaining distance or hire a sedan chair carried by porters.

The journey offers breathtaking views of the surrounding hills, lush forests, and traditional Mon villages, providing an immersive experience into Myanmar's natural beauty and cultural heritage.

Kyaiktiyo Pagoda is more than just a tourist destination; it's a profound symbol of Myanmar's spiritual heritage. The golden glow of the rock at sunrise and sunset, combined with the serene mountain atmosphere, creates an unforgettable experience for all who visit. Whether drawn by its religious significance, its natural wonder, or the allure of its legend, the Golden Rock promises a journey of discovery and reflection. –

References

– kyaiktiyopagoda.org

– Go-Myanmar.com

– Global New Light of Myanmar

MANLE Sayadaw (1842-1921) and Ledi Sayadaw (1 December 1846-27 June 1923) were contemporary Buddhist monk-scholars who made notable contributions to Buddhist doctrine in their discourses and writings which have enriched Myanmar literature.

MANLE Sayadaw (1842-1921) and Ledi Sayadaw (1 December 1846-27 June 1923) were contemporary Buddhist monk-scholars who made notable contributions to Buddhist doctrine in their discourses and writings which have enriched Myanmar literature.

In the 17 and 24 November 2024 issues of The Global New Light of Myanmar, I have translated and reproduced the original vernacular two poems (in a sense ‘doggerels’) written by the two revered monks. The poem by Manle Sayadaw deals with the disadvantages, indeed one could say negative consequences of drinking tea. On the other hand, Ledi Sayadaw listed the benefits of drinking tea and complimented the tea drinkers. The two poems appeared one after the other in the booklet Selected Burmese Poems for 1st and 2nd-year students at the University of Mandalay first published in October 1986.

It is presumable that the poem by Ledi Sayadaw praising the benefits of drinking tea was composed by him after he came across the elder (in age) Manle Sayadaw’s poem censuring tea drinkers. In the mid-18th to early 20th century when the two poems were supposedly composed there was no postal service, not to say radio or telegrams (perhaps). Facebook, Viber and WhatsApp were much more than a century away in the future. Hence it must have been several weeks or a few months before Ledi Sayadaw came across Manle Sayadaw’s poem listing the negative effects of tea drinking. Or — this is only a guess — were there literary symposia during the last two kings of Upper Burma? In the days of King Mindon (8 July 1808-1 October 1878, reigned 1853-78) and King Thibaw (1 January 1859-19 December 1916, reigned 1878-85) there could be literary symposia in court. The two Sayadaws must have been between the ages of 22 to 44 (Manle Sayadaw) and the ages of 18-39 (Ledi Sayadaw) during the reigns of Mindon and Thibaw. Did either of the two kings request the two revered monks to compose poems about the advantages and disadvantages of drinking tea? Perhaps or perhaps not.

One wonders what ‘triggered’ Manle Sayadaw to compose the ‘anti-tea-drinking poem’ or for that matter on the off-chance that it

was Ledi Sayadaw who first composed the ‘pro-tea-drinking’ poem what prompted Ledi Sayadaw to do so.

I am not aware whether there were — or not — other poems or indeed discourses by the two revered monks where they did not see eye to eye on things not only about tea drinking but also on other mundane as well as religious matters.

The rivalry between two Buddhist monks of the 15th to 16th centuries: Shin Maharatha Ratthasara and Shin Maha Silavamsa Two Buddhist monks contemporaneously flourished in the mid-15th to early-16th centuries. Their contributions to Myanmar literature are also very significant.

Indeed, it could be stated that they are landmarks in medieval Burmese literature. They were Shin (Shin is not a ‘first name’ as such but an honorific denoting, a learned monk) Maha (Maha is also an honorific generally meaning ‘great’) Ratthasara (1468-1529) (hereafter Ratthasara) and Shin Maha Silavamsa (1453-1518) (hereafter Silavamsa). Silavamsa is 15 years older than Ratthasara.

I have ‘wondered’ above whether Manle Sayadaw and Ledi Sayadaw were requested by the two last Burmese kings to compose on the topic of drinking tea.

But over three centuries earlier in the palace of the then Innwa (Ava) kings there were literary symposiums where the two monks Silavamsa and Ratthasara were (shall we say) enjoined to compose poems, prose and other literary genres before a live audience. Myanmar language and literature scholars throughout the centuries have debated and expressed their views on the comparative literary contributions, styles and merits of the two medieval monks.

Scholars have stated their views as to whose literary work Silavamsa or Ratthasara were ‘better’ or ‘superior’. One epigram whose origin this writer does not know states to the effect that Silavamsa’s literary achievements were like diamonds cutting not merely through baskets (Taung Go Ma Phaut) but through the mountains (Taun Go Phaut Thi).

Hence Silavamsa’s literary products were like diamonds (Sain Kyaut A-thwin Thila Win). In comparison or indeed in contrast Ratthathara’s literary prose and poetry are merely thorn-like tools which pierced baskets but not mountains (Taun Go Ma Phaut Taung Go Phaut Thi Hsu Hsauk Pamar Ratta Tha).

From the above statement, it is clear that the writer(s) of the epigram were of the view that Silavamsa was the ‘superior’ literati.

Was Silavamsa superior in all or most of his literary products compared to Ratthasara? In his most recent book titled (in translation) Myanmar Language: References to Sixty Treatises (published November 2024) Saya Maung Khin Min (Danubyu) (born 2 January1942) quoted Bagan Wun Htauk U Tin (1861-1933) who himself referred to Kinwun Mingyi U Kaung (3 February 1822-30 June 1908).

Kinwun Mingyi stated that Silavamsa’s poetry is good in meaning and is inspiring. Kinwun Mingyi stated though that as to rhyme

and cadence Ratthasara was the superior writer (on page 23 of Maung Khin Min’s book). Almost certainly there could be a comparative commentary on the literary contributions of the two scholar monks of the mid19th to early 20th century (Manle Sayadaw and Ledi Sayadaw) as there were perhaps more extensive analyses and commentaries of the two monk-poet-literati of the mid-15th to early 16th century.

Are there any Master’s or doctoral theses in the Myanmar language in the various Departments of Myanmar comparing the literary contributions of Manle Sayadaw and Ledi Sayadaw? If there are any books or treatises comparing the literary flair, styles and contributions of Manle Sayadaw and Ledi Sayadaw in both Myanmar and even in the English language yours truly would appreciate learning from them.

Source- The Global New Light of Myanmar

MANLE Sayadaw (1842-1921) and Ledi Sayadaw (1 December 1846-27 June 1923) were contemporary Buddhist monk-scholars who made notable contributions to Buddhist doctrine in their discourses and writings which have enriched Myanmar literature.

In the 17 and 24 November 2024 issues of The Global New Light of Myanmar, I have translated and reproduced the original vernacular two poems (in a sense ‘doggerels’) written by the two revered monks. The poem by Manle Sayadaw deals with the disadvantages, indeed one could say negative consequences of drinking tea. On the other hand, Ledi Sayadaw listed the benefits of drinking tea and complimented the tea drinkers. The two poems appeared one after the other in the booklet Selected Burmese Poems for 1st and 2nd-year students at the University of Mandalay first published in October 1986.

It is presumable that the poem by Ledi Sayadaw praising the benefits of drinking tea was composed by him after he came across the elder (in age) Manle Sayadaw’s poem censuring tea drinkers. In the mid-18th to early 20th century when the two poems were supposedly composed there was no postal service, not to say radio or telegrams (perhaps). Facebook, Viber and WhatsApp were much more than a century away in the future. Hence it must have been several weeks or a few months before Ledi Sayadaw came across Manle Sayadaw’s poem listing the negative effects of tea drinking. Or — this is only a guess — were there literary symposia during the last two kings of Upper Burma? In the days of King Mindon (8 July 1808-1 October 1878, reigned 1853-78) and King Thibaw (1 January 1859-19 December 1916, reigned 1878-85) there could be literary symposia in court. The two Sayadaws must have been between the ages of 22 to 44 (Manle Sayadaw) and the ages of 18-39 (Ledi Sayadaw) during the reigns of Mindon and Thibaw. Did either of the two kings request the two revered monks to compose poems about the advantages and disadvantages of drinking tea? Perhaps or perhaps not.

One wonders what ‘triggered’ Manle Sayadaw to compose the ‘anti-tea-drinking poem’ or for that matter on the off-chance that it

was Ledi Sayadaw who first composed the ‘pro-tea-drinking’ poem what prompted Ledi Sayadaw to do so.

I am not aware whether there were — or not — other poems or indeed discourses by the two revered monks where they did not see eye to eye on things not only about tea drinking but also on other mundane as well as religious matters.

The rivalry between two Buddhist monks of the 15th to 16th centuries: Shin Maharatha Ratthasara and Shin Maha Silavamsa Two Buddhist monks contemporaneously flourished in the mid-15th to early-16th centuries. Their contributions to Myanmar literature are also very significant.

Indeed, it could be stated that they are landmarks in medieval Burmese literature. They were Shin (Shin is not a ‘first name’ as such but an honorific denoting, a learned monk) Maha (Maha is also an honorific generally meaning ‘great’) Ratthasara (1468-1529) (hereafter Ratthasara) and Shin Maha Silavamsa (1453-1518) (hereafter Silavamsa). Silavamsa is 15 years older than Ratthasara.

I have ‘wondered’ above whether Manle Sayadaw and Ledi Sayadaw were requested by the two last Burmese kings to compose on the topic of drinking tea.

But over three centuries earlier in the palace of the then Innwa (Ava) kings there were literary symposiums where the two monks Silavamsa and Ratthasara were (shall we say) enjoined to compose poems, prose and other literary genres before a live audience. Myanmar language and literature scholars throughout the centuries have debated and expressed their views on the comparative literary contributions, styles and merits of the two medieval monks.

Scholars have stated their views as to whose literary work Silavamsa or Ratthasara were ‘better’ or ‘superior’. One epigram whose origin this writer does not know states to the effect that Silavamsa’s literary achievements were like diamonds cutting not merely through baskets (Taung Go Ma Phaut) but through the mountains (Taun Go Phaut Thi).

Hence Silavamsa’s literary products were like diamonds (Sain Kyaut A-thwin Thila Win). In comparison or indeed in contrast Ratthathara’s literary prose and poetry are merely thorn-like tools which pierced baskets but not mountains (Taun Go Ma Phaut Taung Go Phaut Thi Hsu Hsauk Pamar Ratta Tha).

From the above statement, it is clear that the writer(s) of the epigram were of the view that Silavamsa was the ‘superior’ literati.

Was Silavamsa superior in all or most of his literary products compared to Ratthasara? In his most recent book titled (in translation) Myanmar Language: References to Sixty Treatises (published November 2024) Saya Maung Khin Min (Danubyu) (born 2 January1942) quoted Bagan Wun Htauk U Tin (1861-1933) who himself referred to Kinwun Mingyi U Kaung (3 February 1822-30 June 1908).

Kinwun Mingyi stated that Silavamsa’s poetry is good in meaning and is inspiring. Kinwun Mingyi stated though that as to rhyme

and cadence Ratthasara was the superior writer (on page 23 of Maung Khin Min’s book). Almost certainly there could be a comparative commentary on the literary contributions of the two scholar monks of the mid19th to early 20th century (Manle Sayadaw and Ledi Sayadaw) as there were perhaps more extensive analyses and commentaries of the two monk-poet-literati of the mid-15th to early 16th century.

Are there any Master’s or doctoral theses in the Myanmar language in the various Departments of Myanmar comparing the literary contributions of Manle Sayadaw and Ledi Sayadaw? If there are any books or treatises comparing the literary flair, styles and contributions of Manle Sayadaw and Ledi Sayadaw in both Myanmar and even in the English language yours truly would appreciate learning from them.

Source- The Global New Light of Myanmar

WHEN I came out of the lift, I found myself on the bridge-like roofed passageway which connected the lift shaft with the pagoda platform. From the passageway, I got a bird’s eye view of the sprawling Yangon City. I espied in the distance some skyscrapers rising starkly into the sky and a medley of red roofs of the houses hidden amongst the greens of the trees.

WHEN I came out of the lift, I found myself on the bridge-like roofed passageway which connected the lift shaft with the pagoda platform. From the passageway, I got a bird’s eye view of the sprawling Yangon City. I espied in the distance some skyscrapers rising starkly into the sky and a medley of red roofs of the houses hidden amongst the greens of the trees.

The entire landscape was bathing dreamily in the golden rays of the rising sun. Our team headed slowly towards the pagoda glistening in the glow of the morning sun. It was a day to be remembered by our family members, for it was the 79th birthday of our beloved mother. We were now on the platform of the Shwedagon Pagoda to celebrate her birthday.

As it was a weekday, there were only a few pilgrims on the pagoda platform. I saw a couple of lovers paying homage to the pagoda, sitting on the victorious ground (အောင်မြေ ). Buddhists believe that the victorious ground can bring the fulfilment of our wishes. With this thought in our minds, we also sat down on this sacred ground and paid homage to the pagoda wishing that our mother would enjoy good health, happiness and longevity. Then, leaving behind my mother and sisters who were telling beads in the victorious ground, I walked clockwise round the base of the pagoda. I found shrine rooms housing the Kakusandha Buddha, the Konagamana Buddha, the Kassapa Buddha and the Gotama Buddha at the four cardinal points of the pagoda and some rest houses and pavilions surmounted by a multi-tiered roof round the pagoda platform.

Inside these buildings were some devotees meditating, reciting discourses (Sutta) and doing other religious services. While walking, I had a chance to observe the Shwedagon Pagoda at a close range. I was filled with awe and wonderment at the great height of the pagoda and its excellently artistic works. Its body coated in gold plates was erected on three receding terraces. Its part above the bell-shaped dome was decorated with projected bands, upturned and downturned lotus flowers, banana buds, etc. and tapered towards the spire crowned with a gem-studded sacred umbrella. Its base was encircled by 64 small stupas. Some devotees were pouring water over small seated Buddha images next to the planetary posts near the base of the pagoda. The building on the platform which attracted my attention most was the Rakhine Prayer Hall, a pavilion with a multi-tiered roof. It lies between the southern and western covered stairways.

It was built entirely of wood and richly decorated with elaborate and exquisite floral designs. It is said that it was donated by two Rakhine brokers in 1910. I saw the Buddha Museum next to the entrance to the western-covered stairway. Out of curiosity, I entered it and found the walls and the ceiling depicting some episodes of the Ten Major Jataka Stories. Moreover, many antique Buddhist artefacts like Buddha images, miniature stupas etc made of gold and silver were put on display in the showcases.

Then I weaved my way through the buildings on the platform and noticed some Buddha images and small pagodas standing in the yards behind the rest houses and Tazaungs. Among them were the Shin Saw Pu Buddha images, the Naungdawgyi Pagoda and the Shinmahtee Buddha Image. I also noticed some Nat shrines under the Banyan trees growing at the edges of the top of the pagoda hill. It is thought that the Shin Saw Pu Buddha Image was built by Queen Shin Saw Pu while she was living a peaceful life in a make-shift palace not far from the Shwedagon Pagoda after she had handed over her Hamsavati throne to King Dhammaceti, her son-in-law. Legend has it that the Shinmahtee Buddha Image was built by a monk named ‘Shinmahtee’, who was an alchemist, about 1,000 years ago. The Naungdawgyi Pagoda was built by King Naungdawgyi, a son of King Alaungphaya, during the 18th century AD.

I got into a Tazaung in the northeast corner of the precincts. I found there the historic King Thayawady Bell which was decorated with four-lion figures. It was donated by King Thayawady and it weighs 25,940 visses and 49 ticals or 42 tonnes. It was cast in the year 1204 of the Myanmar Era. Its official name is Mahatisadhaghanta. It measures nine cubits in height, five cubits in diameter at the mouth and 15 cubits in circumference. It contains one hundred lines. This bell inscription is about the eulogy on nine attributes of Lord Buddha, benefits of the life of the monks, birth stories of the Buddha, his donations made at the Shwedagon Pagoda, his aspirations to the Bodhisatta etc.

A little down from the platform, there was a shed in which a three-stone inscription was erected near the entrance to the eastern covered stairway. It was the Shwedagon Stone Inscription inscribed by King Dhammaceti in 1485. It is about the history of the Shwedagon Pagoda: the two merchants brothers Tapussa and Ballikha crossed the ocean, came upon the newly-enlightened Buddha in Majjhimadesa and got eight hair relics. On their return to their native Okkalapa, King Okkala and his mother Meihlamu

had the Shwedagon Pagoda built, enshrining these eight hair relics in the relic chamber.

Then, I walked back to the zayat near the victorious ground where my mother and elder sister were waiting for me. We left pagoda at 11 am. On the way back, we stopped over at a restaurant to celebrate our mother’s birthday. We had lunch merrily there. Then, we returned home straight. To conclude, it was worthwhile to visit the Shwedagon Pagoda. We enjoyed a good time on our mother’s auspicious birthday. Moreover, we could earn the merits and also get historical and archaeological knowledge.

Source- The Global New Light of Myanmar

WHEN I came out of the lift, I found myself on the bridge-like roofed passageway which connected the lift shaft with the pagoda platform. From the passageway, I got a bird’s eye view of the sprawling Yangon City. I espied in the distance some skyscrapers rising starkly into the sky and a medley of red roofs of the houses hidden amongst the greens of the trees.

The entire landscape was bathing dreamily in the golden rays of the rising sun. Our team headed slowly towards the pagoda glistening in the glow of the morning sun. It was a day to be remembered by our family members, for it was the 79th birthday of our beloved mother. We were now on the platform of the Shwedagon Pagoda to celebrate her birthday.

As it was a weekday, there were only a few pilgrims on the pagoda platform. I saw a couple of lovers paying homage to the pagoda, sitting on the victorious ground (အောင်မြေ ). Buddhists believe that the victorious ground can bring the fulfilment of our wishes. With this thought in our minds, we also sat down on this sacred ground and paid homage to the pagoda wishing that our mother would enjoy good health, happiness and longevity. Then, leaving behind my mother and sisters who were telling beads in the victorious ground, I walked clockwise round the base of the pagoda. I found shrine rooms housing the Kakusandha Buddha, the Konagamana Buddha, the Kassapa Buddha and the Gotama Buddha at the four cardinal points of the pagoda and some rest houses and pavilions surmounted by a multi-tiered roof round the pagoda platform.

Inside these buildings were some devotees meditating, reciting discourses (Sutta) and doing other religious services. While walking, I had a chance to observe the Shwedagon Pagoda at a close range. I was filled with awe and wonderment at the great height of the pagoda and its excellently artistic works. Its body coated in gold plates was erected on three receding terraces. Its part above the bell-shaped dome was decorated with projected bands, upturned and downturned lotus flowers, banana buds, etc. and tapered towards the spire crowned with a gem-studded sacred umbrella. Its base was encircled by 64 small stupas. Some devotees were pouring water over small seated Buddha images next to the planetary posts near the base of the pagoda. The building on the platform which attracted my attention most was the Rakhine Prayer Hall, a pavilion with a multi-tiered roof. It lies between the southern and western covered stairways.

It was built entirely of wood and richly decorated with elaborate and exquisite floral designs. It is said that it was donated by two Rakhine brokers in 1910. I saw the Buddha Museum next to the entrance to the western-covered stairway. Out of curiosity, I entered it and found the walls and the ceiling depicting some episodes of the Ten Major Jataka Stories. Moreover, many antique Buddhist artefacts like Buddha images, miniature stupas etc made of gold and silver were put on display in the showcases.

Then I weaved my way through the buildings on the platform and noticed some Buddha images and small pagodas standing in the yards behind the rest houses and Tazaungs. Among them were the Shin Saw Pu Buddha images, the Naungdawgyi Pagoda and the Shinmahtee Buddha Image. I also noticed some Nat shrines under the Banyan trees growing at the edges of the top of the pagoda hill. It is thought that the Shin Saw Pu Buddha Image was built by Queen Shin Saw Pu while she was living a peaceful life in a make-shift palace not far from the Shwedagon Pagoda after she had handed over her Hamsavati throne to King Dhammaceti, her son-in-law. Legend has it that the Shinmahtee Buddha Image was built by a monk named ‘Shinmahtee’, who was an alchemist, about 1,000 years ago. The Naungdawgyi Pagoda was built by King Naungdawgyi, a son of King Alaungphaya, during the 18th century AD.

I got into a Tazaung in the northeast corner of the precincts. I found there the historic King Thayawady Bell which was decorated with four-lion figures. It was donated by King Thayawady and it weighs 25,940 visses and 49 ticals or 42 tonnes. It was cast in the year 1204 of the Myanmar Era. Its official name is Mahatisadhaghanta. It measures nine cubits in height, five cubits in diameter at the mouth and 15 cubits in circumference. It contains one hundred lines. This bell inscription is about the eulogy on nine attributes of Lord Buddha, benefits of the life of the monks, birth stories of the Buddha, his donations made at the Shwedagon Pagoda, his aspirations to the Bodhisatta etc.

A little down from the platform, there was a shed in which a three-stone inscription was erected near the entrance to the eastern covered stairway. It was the Shwedagon Stone Inscription inscribed by King Dhammaceti in 1485. It is about the history of the Shwedagon Pagoda: the two merchants brothers Tapussa and Ballikha crossed the ocean, came upon the newly-enlightened Buddha in Majjhimadesa and got eight hair relics. On their return to their native Okkalapa, King Okkala and his mother Meihlamu

had the Shwedagon Pagoda built, enshrining these eight hair relics in the relic chamber.

Then, I walked back to the zayat near the victorious ground where my mother and elder sister were waiting for me. We left pagoda at 11 am. On the way back, we stopped over at a restaurant to celebrate our mother’s birthday. We had lunch merrily there. Then, we returned home straight. To conclude, it was worthwhile to visit the Shwedagon Pagoda. We enjoyed a good time on our mother’s auspicious birthday. Moreover, we could earn the merits and also get historical and archaeological knowledge.

Source- The Global New Light of Myanmar

MORALITY means Sila in the Pali Language. Morality denotes being virtuous and abstaining from evil actions, both physical and verbal. It also prescribes virtuous conduct (Carita Sila, စာရိတ္တသီလ)

In our Theravada Buddhism, Morality is based on abstention or avoidance. Morality, which is based on the observance of abstention decreed by the noble Buddha, is Caritta Sila, စာရိတ္တသီလ

MORALITY means Sila in the Pali Language. Morality denotes being virtuous and abstaining from evil actions, both physical and verbal. It also prescribes virtuous conduct (Carita Sila, စာရိတ္တသီလ)

In our Theravada Buddhism, Morality is based on abstention or avoidance. Morality, which is based on the observance of abstention decreed by the noble Buddha, is Caritta Sila, စာရိတ္တသီလ

Constant observance of the five precepts, etc. (Niece sila, နိစ္စသီလ) is fulfilled through abstentions.

By moral obligations, certain obligations must be fulfilled. In Buddhist ethics, certain moral obligations are incumbent on one, such as paying respects, welcoming, making obeisance, showing reverence and attending to elders who may be senior in age or in status, and one has to fulfil them.

Observing the precepts in abandoning sensual desire. The eight moral precepts consist of the observance of the following factors: -

(1) Abstaining from killing any living being,

(၁) သူ့အသက်သတ်ခြင်းမှ ရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်း

(2) Abstaining from taking what is not gives

(၂) ပိုင်ရှင်မပေးသော ပစ္စည်းဥစ္စာကို ခိုးယူခြင်းမှ ရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်း

(3) Abstaining from unchastity,

(၃) မမြတ်သောမေထုန်အကျင့်မှ ရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်း

(4) Abstaining from telling lies,

(၄) မဟုတ်မမှန်ရသာစကားတို့ကို ပြောဆိုခြင်းမှရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်း

(5) Abstaining from taking liquors and intoxicants, which can lead one to forgetfulness,

(၅) မူးယစ်မေ့လျော့စေတတ်သော သေရည်သေရက် မူးယစ်ဆေးဝါးများကို သုံးစွဲခြင်းမှ ရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်း

(6) Abstaining from taking food after mid-day,

(၆) နေ့လွဲ ညစာစားခြင်းမှ ရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်း

(7) Abstaining from dancing, singing, playing musical instruments, seeing shows, wearing flowers and using perfumes,

(၇) ကခုန်ခြင်း၊ သီဆိုခြင်း၊ တီးမှုတ်ခြင်းတို့ကို ကြည့်ရှုနားထောင်ခြင်းနှင့် ပန်းနံ့သာအမွှေးအကြိုင်များကို ပန်ဆင်လိမ်းကျံ တန်ဆာဆင်ခြင်းတို့မှ ရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်း

(8) Abstaining from using high and luxurious beds, seats, etc.

(၈) မြင့်သောနေရာ၊ မြတ်သောနေရာတို့ကို အသုံးပြုခြင်းတို့ကို ရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်းတို့ဖြစ်ကြသည်။

Morality is always used to prevent and avoid the unbeneficial Akusala Kamma. Two types of actions may be discerned: -

(1) Action which destroys the unbeneficial and produces the beneficial (Kusala Kamma)

(2) Action which destroys the beneficial and produces the unbeneficial (Akusala Kamma)

There are three kinds of action: -

(1) Physical Action (Kaya Kamma) (2) Verbal Action (Vici Kamma) (3) Mental Action (Mara Kamma)

Character is power in our human society. People are social animals, so it is said that when we live together in the form of society, we need a body of laws to keep peace and ensure justice for all members, without which it would be impossible for society

to function. We can say, therefore, that all of us are under the protection of the law. The noble Buddha speaks about a different form of protection, a far superior one. If we earnestly practice them. They are: -

(1) Hiri (ဟီရိ) = Shame at doing evil (Moral Shame, and မကောင်းမှုကိုပြုလုပ်ရန်ရှက်ခြင်း)

(2) Ottappu (ဩတ္တပ္ပ) = Fear of the results of doing evil (Moral Dread, မကောင်းမှုကိုပြုလုပ်ရန် ကြောက်ခြင်း

Hiri is moral shame or conscience. It wises out of an understanding of what is right or wrong, good or bad, and is developed through a constant application of moral vigilance.

A person who practices Hiri does not do anything rashly or without proper forethought but will always exercise precaution in all actions. Before doing anything, he wisely asks himself, “Is it right or wrong?” “Is it good or bad?”. If he finds it to be wrong or bad, he will not do it, no matter what the temptation. If, however, what he intends to do is right and good, he will make an effort to finish the task and will not give up.

Hiri can be compared to the feeling of being over the fire, which a person who loves cleanliness may experience when he sees something disgusting. He may not, for instance, put his hand into a trash bag full of stinking garbage if he can avoid it.

When he comes across a puddle of mud and dirt, he will stop aside to avoid getting himself and his clothes smudged.

Likewise, an individual who practices Hiri feels disgusted with all bad actions, physical, verbal and mental, and endeavours to avoid them as much as possible.

He does not do such things as stamping his feet before his parents, talking impolitely back at them, or having an unkind and unrespectful thought towards them, for he knows that such as bed and unbecoming of a good Buddhist and would make their parents very unhappy indeed.

Ottappa is moral dread or fear of doing something wrong or immoral. It is the result of a firm’s belief in the doctrine of Kamma, which states that a willful action brings about an appropriate consequence sooner or later.

An individual who has Ottappa is afraid to do evil deeds because he knows that they will bring evil results and unhappiness to himself and others. He will not, on the other hand, hesitate to do the right things, firmly believing that the consequences thereof will be pleasant and beneficial. Unfortunately, people tend to do just the opposite of what they should. They are brave to do evil but afraid to do good.

Ottappa can be compared to the fear of a poisonous snake.

Just as an individual avoids the snakebite, knowing that such is fatal, even so, an Ottappal person tries to avoid evil because he knows that consequences are painful. He does not do wrong things even when he is sure that he will not be caught, for he understands that the law of Kamma operates at all times and in all places. For this reason, also he is encouraged to do good even if no one else notices it or acknowledges his good deeds.

In my opinion, if people practice these two virtues, this world will, indeed, be well protected, and there will be less need for law. No evil deed will be committed even in secrecy. The world will thus be a very happy place for us all. Therefore, the two virtues (Hiri and Ottappa) are the highest ethics or morality for world peace forever.

Ref:

(1) A Dictionary of Buddhist Terms (Ministry of Religious Affairs, Myanmar, 2003)

(2) Basic Buddha Course By Phra Sunthorn Plamintr, PhD (Buddha Dhamma Meditation Centre, USA, 1987

Source- The Global New Light of Myanmar

MORALITY means Sila in the Pali Language. Morality denotes being virtuous and abstaining from evil actions, both physical and verbal. It also prescribes virtuous conduct (Carita Sila, စာရိတ္တသီလ)

In our Theravada Buddhism, Morality is based on abstention or avoidance. Morality, which is based on the observance of abstention decreed by the noble Buddha, is Caritta Sila, စာရိတ္တသီလ

Constant observance of the five precepts, etc. (Niece sila, နိစ္စသီလ) is fulfilled through abstentions.

By moral obligations, certain obligations must be fulfilled. In Buddhist ethics, certain moral obligations are incumbent on one, such as paying respects, welcoming, making obeisance, showing reverence and attending to elders who may be senior in age or in status, and one has to fulfil them.

Observing the precepts in abandoning sensual desire. The eight moral precepts consist of the observance of the following factors: -

(1) Abstaining from killing any living being,

(၁) သူ့အသက်သတ်ခြင်းမှ ရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်း

(2) Abstaining from taking what is not gives

(၂) ပိုင်ရှင်မပေးသော ပစ္စည်းဥစ္စာကို ခိုးယူခြင်းမှ ရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်း

(3) Abstaining from unchastity,

(၃) မမြတ်သောမေထုန်အကျင့်မှ ရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်း

(4) Abstaining from telling lies,

(၄) မဟုတ်မမှန်ရသာစကားတို့ကို ပြောဆိုခြင်းမှရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်း

(5) Abstaining from taking liquors and intoxicants, which can lead one to forgetfulness,

(၅) မူးယစ်မေ့လျော့စေတတ်သော သေရည်သေရက် မူးယစ်ဆေးဝါးများကို သုံးစွဲခြင်းမှ ရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်း

(6) Abstaining from taking food after mid-day,

(၆) နေ့လွဲ ညစာစားခြင်းမှ ရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်း

(7) Abstaining from dancing, singing, playing musical instruments, seeing shows, wearing flowers and using perfumes,

(၇) ကခုန်ခြင်း၊ သီဆိုခြင်း၊ တီးမှုတ်ခြင်းတို့ကို ကြည့်ရှုနားထောင်ခြင်းနှင့် ပန်းနံ့သာအမွှေးအကြိုင်များကို ပန်ဆင်လိမ်းကျံ တန်ဆာဆင်ခြင်းတို့မှ ရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်း

(8) Abstaining from using high and luxurious beds, seats, etc.

(၈) မြင့်သောနေရာ၊ မြတ်သောနေရာတို့ကို အသုံးပြုခြင်းတို့ကို ရှောင်ကြဉ်ခြင်းတို့ဖြစ်ကြသည်။

Morality is always used to prevent and avoid the unbeneficial Akusala Kamma. Two types of actions may be discerned: -

(1) Action which destroys the unbeneficial and produces the beneficial (Kusala Kamma)

(2) Action which destroys the beneficial and produces the unbeneficial (Akusala Kamma)

There are three kinds of action: -

(1) Physical Action (Kaya Kamma) (2) Verbal Action (Vici Kamma) (3) Mental Action (Mara Kamma)

Character is power in our human society. People are social animals, so it is said that when we live together in the form of society, we need a body of laws to keep peace and ensure justice for all members, without which it would be impossible for society

to function. We can say, therefore, that all of us are under the protection of the law. The noble Buddha speaks about a different form of protection, a far superior one. If we earnestly practice them. They are: -

(1) Hiri (ဟီရိ) = Shame at doing evil (Moral Shame, and မကောင်းမှုကိုပြုလုပ်ရန်ရှက်ခြင်း)

(2) Ottappu (ဩတ္တပ္ပ) = Fear of the results of doing evil (Moral Dread, မကောင်းမှုကိုပြုလုပ်ရန် ကြောက်ခြင်း

Hiri is moral shame or conscience. It wises out of an understanding of what is right or wrong, good or bad, and is developed through a constant application of moral vigilance.

A person who practices Hiri does not do anything rashly or without proper forethought but will always exercise precaution in all actions. Before doing anything, he wisely asks himself, “Is it right or wrong?” “Is it good or bad?”. If he finds it to be wrong or bad, he will not do it, no matter what the temptation. If, however, what he intends to do is right and good, he will make an effort to finish the task and will not give up.

Hiri can be compared to the feeling of being over the fire, which a person who loves cleanliness may experience when he sees something disgusting. He may not, for instance, put his hand into a trash bag full of stinking garbage if he can avoid it.

When he comes across a puddle of mud and dirt, he will stop aside to avoid getting himself and his clothes smudged.

Likewise, an individual who practices Hiri feels disgusted with all bad actions, physical, verbal and mental, and endeavours to avoid them as much as possible.

He does not do such things as stamping his feet before his parents, talking impolitely back at them, or having an unkind and unrespectful thought towards them, for he knows that such as bed and unbecoming of a good Buddhist and would make their parents very unhappy indeed.

Ottappa is moral dread or fear of doing something wrong or immoral. It is the result of a firm’s belief in the doctrine of Kamma, which states that a willful action brings about an appropriate consequence sooner or later.

An individual who has Ottappa is afraid to do evil deeds because he knows that they will bring evil results and unhappiness to himself and others. He will not, on the other hand, hesitate to do the right things, firmly believing that the consequences thereof will be pleasant and beneficial. Unfortunately, people tend to do just the opposite of what they should. They are brave to do evil but afraid to do good.

Ottappa can be compared to the fear of a poisonous snake.

Just as an individual avoids the snakebite, knowing that such is fatal, even so, an Ottappal person tries to avoid evil because he knows that consequences are painful. He does not do wrong things even when he is sure that he will not be caught, for he understands that the law of Kamma operates at all times and in all places. For this reason, also he is encouraged to do good even if no one else notices it or acknowledges his good deeds.

In my opinion, if people practice these two virtues, this world will, indeed, be well protected, and there will be less need for law. No evil deed will be committed even in secrecy. The world will thus be a very happy place for us all. Therefore, the two virtues (Hiri and Ottappa) are the highest ethics or morality for world peace forever.

Ref:

(1) A Dictionary of Buddhist Terms (Ministry of Religious Affairs, Myanmar, 2003)

(2) Basic Buddha Course By Phra Sunthorn Plamintr, PhD (Buddha Dhamma Meditation Centre, USA, 1987

Source- The Global New Light of Myanmar