Myanmar women have preserved the noble traditions and customs from generation to generation. The efforts of these women in safeguarding such traditions are also prominently reflected in the literature that emerged across different eras.

Myanmar women have preserved the noble traditions and customs from generation to generation. The efforts of these women in safeguarding such traditions are also prominently reflected in the literature that emerged across different eras.

According to the 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census, number of women accounted for approximately 29.4 million out of the total population of around 56.2 million, indicating that more than half of the country’s population is women. Being a Union made up of over 100 different ethnic groups, Myanmar is home to a wide diversity of traditional cultures, customs, languages, dress, historical backgrounds, and geographical features.

In the present day, Myanmar women not only shoulder the traditional role of household responsibilities, but also keep abreast with men in contributing to both personal and social progress. As women are considered a vulnerable group, it is essential to protect and nurture their lives, ensuring their well-being and empowerment. At the same time, their rights and livelihoods must be safeguarded and promoted, particularly in the areas of education, healthcare, economy, social development, and overall security for young women. Women themselves must also strive to preserve and uphold the dignity and value of womanhood.

An important aspect for Myanmar women is the preservation of their ethnic traditions, cultural customs, national pride, and dignity. These values must be safeguarded to ensure that they are neither diminished nor lost. Therefore, it is essential to continuously foster a mindset that cherishes and values the lives of women, promoting a spirit of respect, pride, and cultural identity throughout their lives. Myanmar people should know their tradition and culture and should not value others’ cultures while preserving their tradition and culture, and this includes traditional dress and customs.

Myanmar girls and women wore traditional garments such as Yin Phone and longyi, following the attitudes of their parents. They gracefully wear Myanmar traditional dress at religious events, pagoda festivals and donation events. However, some young people may be considered reckless for wearing skirts, shorts and long pants in ways that may damage Myanmar culture.

Myanmar women are the rising stars of the future, and they should wear safe and fine dresses as they are living in a country with the proclamation of Buddhism. Moreover, they can be known as Myanmar by the tourists whenever they see them wearing a Myanmar dress.

Myanmar girls serve as role models in preserving traditional cultural heritage by wearing Yin Phone and longyi. Naturally calm and composed, Myanmar women are also known for their gentle and graceful demeanour, which contributes to their dignified feminine charm.

Therefore, from major cities to rural areas, Myanmar’s traditional cultural heritage should be preserved. The beauty of traditional attire and customs, which deserves to be honoured as a form of cultural art, should be portrayed by artists as a masterpiece delicately painted with the skilled brushstrokes of Myanmar culture.

Just as Myanmar women rightfully possess the tradition of wearing cultural attire, they should also uphold modesty and a sense of decency in how they dress. Their clothing should be neither too plain nor overly extravagant, neither outdated nor excessively modern. By wearing traditional Myanmar dress, which is most pleasing to the eye, heartwarming to the soul, and rich in elegance and dignity, they help preserve the beauty and cultural heritage of Myanmar women today and pass it down as a cherished legacy to future generations of young girls. This article is created in honour of the Myanmar Women’s Day, which will fall on 3 July 2025.

Translated by KTZH

Source: GNLM

Myanmar women have preserved the noble traditions and customs from generation to generation. The efforts of these women in safeguarding such traditions are also prominently reflected in the literature that emerged across different eras.

According to the 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census, number of women accounted for approximately 29.4 million out of the total population of around 56.2 million, indicating that more than half of the country’s population is women. Being a Union made up of over 100 different ethnic groups, Myanmar is home to a wide diversity of traditional cultures, customs, languages, dress, historical backgrounds, and geographical features.

In the present day, Myanmar women not only shoulder the traditional role of household responsibilities, but also keep abreast with men in contributing to both personal and social progress. As women are considered a vulnerable group, it is essential to protect and nurture their lives, ensuring their well-being and empowerment. At the same time, their rights and livelihoods must be safeguarded and promoted, particularly in the areas of education, healthcare, economy, social development, and overall security for young women. Women themselves must also strive to preserve and uphold the dignity and value of womanhood.

An important aspect for Myanmar women is the preservation of their ethnic traditions, cultural customs, national pride, and dignity. These values must be safeguarded to ensure that they are neither diminished nor lost. Therefore, it is essential to continuously foster a mindset that cherishes and values the lives of women, promoting a spirit of respect, pride, and cultural identity throughout their lives. Myanmar people should know their tradition and culture and should not value others’ cultures while preserving their tradition and culture, and this includes traditional dress and customs.

Myanmar girls and women wore traditional garments such as Yin Phone and longyi, following the attitudes of their parents. They gracefully wear Myanmar traditional dress at religious events, pagoda festivals and donation events. However, some young people may be considered reckless for wearing skirts, shorts and long pants in ways that may damage Myanmar culture.

Myanmar women are the rising stars of the future, and they should wear safe and fine dresses as they are living in a country with the proclamation of Buddhism. Moreover, they can be known as Myanmar by the tourists whenever they see them wearing a Myanmar dress.

Myanmar girls serve as role models in preserving traditional cultural heritage by wearing Yin Phone and longyi. Naturally calm and composed, Myanmar women are also known for their gentle and graceful demeanour, which contributes to their dignified feminine charm.

Therefore, from major cities to rural areas, Myanmar’s traditional cultural heritage should be preserved. The beauty of traditional attire and customs, which deserves to be honoured as a form of cultural art, should be portrayed by artists as a masterpiece delicately painted with the skilled brushstrokes of Myanmar culture.

Just as Myanmar women rightfully possess the tradition of wearing cultural attire, they should also uphold modesty and a sense of decency in how they dress. Their clothing should be neither too plain nor overly extravagant, neither outdated nor excessively modern. By wearing traditional Myanmar dress, which is most pleasing to the eye, heartwarming to the soul, and rich in elegance and dignity, they help preserve the beauty and cultural heritage of Myanmar women today and pass it down as a cherished legacy to future generations of young girls. This article is created in honour of the Myanmar Women’s Day, which will fall on 3 July 2025.

Translated by KTZH

Source: GNLM

Mass media is broadly used to raise awareness and appreciation of Myanmar’s Thanaka cultural practice and concerted efforts are being exerted to submit nomination proposal of Myanmar’s Thanaka cultural practice by March 2025 to be inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity

Mass media is broadly used to raise awareness and appreciation of Myanmar’s Thanaka cultural practice and concerted efforts are being exerted to submit nomination proposal of Myanmar’s Thanaka cultural practice by March 2025 to be inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity

I was so ecstatic when I heard about those cultural awareness campaigns of Myanmar’s Thanaka that is the legacy of intangible attributes of Myanmar people to safeguard it for future generations and to be submitted for UNESCO’s cultural heritage inscription. I have been a big fan of Thanka who traditionally applies Thanaka to the face since I was young. Therefore, I was overwhelmed by delight. I will be carried away with euphoria when UNESCO adds it to its Intangible Cultural Heritage List.

Myanmar’s Thanaka culture has been passed down from past generations. It can be profoundly traced in the murals of temples in Gyubyaukgyi Temple founded in AD 1113 in Bagan ancient cultural heritage site and Sulamani Temple founded in AD 1183 and murals of other temples.

Additionally, Thanaka applying tradition passing down through generations can be remarkably found in earliest works of literature, stories, poems and folk songs, including mawgun, eigyin, pyo, kagyin, maunghtaung, Lamai peasant girls’ poem and songs, representing deeper symbolic meaning related to the cultural value and tradition rooted for thousand years.

Myanmar people annually celebrate the Thanaka Festival from the full moon of Thadingyut to the full moon of Tazaungdine (31 October to 29 November) beyond the 12-month festival traditions.

Village girls and ladies from Khetthin village in the north of Singu town, Mandalay Region apply Thanaka and Thanaka powder put in bronze cup to pilgrims who flock to Shwe Taung Oo mountain pagoda during the full moon of Thadingyut, signifying unique and beautiful Myanmar’s Thanaka culture.

The word Thanaka, previously called Thana-ka, is derived from Thana (dirt) and Ka (clearing or removing), meaning removing the dirt. Thanaka is a paste made from ground bark which commonly applies to Myanmar people for sun protection, perfume and beauty purposes. It is believed to show a distinct feature of Myanmar people. This natural cosmetic has cooling and soothing effects with good properties for skin. Thanaka is highly admired by Myanmar’s royal courts to peasant ladies nowadays. Other parts of Thanaka tree also have medicinal effects.

Thanaka is credited with medicinal benefits with a warm effect in winter and cooling sensation during hot winter to reduce body heat. This traditional product is highly appreciated and cherished by the whole nation regardless of ages and genders.

Myanmar elder people usually talks about the three basic values (Three Jewels: Buddha, Dharma and Sangha), paying respect to parents and teachers and fostering patriotism towards one’s nation and other inspirational and motivational messages while applying Thanaka to younger people, passing down traditions to younger generations and representing signs of the devotion, respect and love.

Moreover, Thanaka incense is offered to Buddha during ritual face washing ceremonies at Mandalay MahaMyatmuni Temple and Aungtawmu Pagoda in the early morning, unifying symbols of cultural pride and drawing a daily crowd of devotees.

Thanaka can be found in Sri Lanka, India, Thailand, Myanmar and Pakistan. Myanmar’s Thanaka is of premium quality with pleasant and unique fragrance. Shinmataung and Shwebo Thanaka varieties are the most popular among them. Applying Shwebo Thanaka gives one smooth skin and yellowish beauty unlike Shinmataung Thanaka having a sweet and pleasant smell.

Beyond beauty purposes, the whole Thanaka trees (fruits, root, stem, leaves) have good properties and medicinal benefits. Shwepyinan Company established Thanaka museum in NyaungU city in order to disseminate information of Thanaka culture among young communities and conserve cultural heritage. Myanmar Thanaka Planters and Producers Association was formed on 11 November 2017 in order to safeguard cultural heritage and penetrate Thanaka to international markets and raise public awareness in cooperation with non-governmental organization Helvetas Myanmar.

The association organizes Thanaka beauty pageants, Thanaka trade fair and Myanmar Thanaka Day events to pass Thanaka culture on to the next generation and increase admiration for Thanaka.

Thanaka Day was marked on the full moon day of Tabodwe, connecting Buddhist’s tradition of offering light and Thanaka incense to Buddha. Events related to Thanaka including talk shows, distributing pamphlets, donation and offering Thanaka paste to Buddha are held in the precinct of Pagoda on the Thanaka Day.

The association’s statistics indicated that there are 323,000 acres of Thanaka in Myanmar. The association comprises growers and traders from Ayartaw, Shwebo, Kantbalu, Monywa, Myinmu, Butalin, Kanni, Yinmabin, Pakokku, Myaing, Yesagyo, Pauk, Sittway and Langkho areas and companies from big cities like Yangon, Mandalay and Nay Pyi Taw. Stakeholders involved in the Thanaka supply chain are exerting continuous efforts to produce value-added Thanaka products that were commercially valued in international markets and preserving this heritage and passing it on to future generations through documentation, education, community engagement and revitalization maintaining core values and cultural identity.

Myanmar Thanaka culture has existed for thousands of years. The earliest discovery of applying the Thanaka tradition is back in the Bagan Dynasty. The poems written by King Yazadariz’s sprouse (poet) in 14th century and Shin Ratthasara, monk and prominent poet in 15th century invoked Thanaka culture in literary work.

Furthermore, some communities have traditions of holding the Thanaka Grinding Festival on the first day of the Thingyan Festival and Buddha statues are washed by Thanaka paste, preserving universal value.

Literary works in Bagan, Pyu dynasties captured the essence of Myanmar Thanaka culture, providing a rich source of Thanaka value and traditions of Myanmar people wearing it throughout history.

Inscriptions on Kyaukpyin stone slab note the name of King Bayintnaung’s daughter Princess Dartukalaya, placed at Shwemadaw Pagoda, revealing the solid culture of Thanaka in Taungoo dynasty.

Thanaka supplied to court in King Alaungpaya Dynasty were sourced from Kaput village two miles away from the south of Thihataw Pagoda in KhinU Township, Shwebo District, indicating a notable history of Thanaka again.

Consequently, Myanmar Thanaka that people of all ages and gender cherish and apply to face and body portrayed the significance of the heritage throughout history. Myanmar people are committed to preserving and promoting its culture by holding festivals stimulating community engagement and keeping inventory of Thanaka heritage passing through generations. Literary works and social events describing Myanmar Thanaka tradition act as a window to Myanmar’s intangible cultural heritage. I would like to express my deep respect to those endeavouring to submit nomination of Thanaka as a cultural element by March 2025 to be inscribed on the UNESCO’s list.

If Myanmar’s Thanaka culture and tradition that has dominated for thousand years is recognized and listed by UNESCO, it will be national pride and identity. I hereby would like to appreciate their genuine and continuous efforts with Myanmar Thanaka promotion and cultural awareness campaigns. I am praying from my heart for Myanmar Thanaka to move forward to achieve UNESCO’s inscription.

Translated by KK

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

Mass media is broadly used to raise awareness and appreciation of Myanmar’s Thanaka cultural practice and concerted efforts are being exerted to submit nomination proposal of Myanmar’s Thanaka cultural practice by March 2025 to be inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity

I was so ecstatic when I heard about those cultural awareness campaigns of Myanmar’s Thanaka that is the legacy of intangible attributes of Myanmar people to safeguard it for future generations and to be submitted for UNESCO’s cultural heritage inscription. I have been a big fan of Thanka who traditionally applies Thanaka to the face since I was young. Therefore, I was overwhelmed by delight. I will be carried away with euphoria when UNESCO adds it to its Intangible Cultural Heritage List.

Myanmar’s Thanaka culture has been passed down from past generations. It can be profoundly traced in the murals of temples in Gyubyaukgyi Temple founded in AD 1113 in Bagan ancient cultural heritage site and Sulamani Temple founded in AD 1183 and murals of other temples.

Additionally, Thanaka applying tradition passing down through generations can be remarkably found in earliest works of literature, stories, poems and folk songs, including mawgun, eigyin, pyo, kagyin, maunghtaung, Lamai peasant girls’ poem and songs, representing deeper symbolic meaning related to the cultural value and tradition rooted for thousand years.

Myanmar people annually celebrate the Thanaka Festival from the full moon of Thadingyut to the full moon of Tazaungdine (31 October to 29 November) beyond the 12-month festival traditions.

Village girls and ladies from Khetthin village in the north of Singu town, Mandalay Region apply Thanaka and Thanaka powder put in bronze cup to pilgrims who flock to Shwe Taung Oo mountain pagoda during the full moon of Thadingyut, signifying unique and beautiful Myanmar’s Thanaka culture.

The word Thanaka, previously called Thana-ka, is derived from Thana (dirt) and Ka (clearing or removing), meaning removing the dirt. Thanaka is a paste made from ground bark which commonly applies to Myanmar people for sun protection, perfume and beauty purposes. It is believed to show a distinct feature of Myanmar people. This natural cosmetic has cooling and soothing effects with good properties for skin. Thanaka is highly admired by Myanmar’s royal courts to peasant ladies nowadays. Other parts of Thanaka tree also have medicinal effects.

Thanaka is credited with medicinal benefits with a warm effect in winter and cooling sensation during hot winter to reduce body heat. This traditional product is highly appreciated and cherished by the whole nation regardless of ages and genders.

Myanmar elder people usually talks about the three basic values (Three Jewels: Buddha, Dharma and Sangha), paying respect to parents and teachers and fostering patriotism towards one’s nation and other inspirational and motivational messages while applying Thanaka to younger people, passing down traditions to younger generations and representing signs of the devotion, respect and love.

Moreover, Thanaka incense is offered to Buddha during ritual face washing ceremonies at Mandalay MahaMyatmuni Temple and Aungtawmu Pagoda in the early morning, unifying symbols of cultural pride and drawing a daily crowd of devotees.

Thanaka can be found in Sri Lanka, India, Thailand, Myanmar and Pakistan. Myanmar’s Thanaka is of premium quality with pleasant and unique fragrance. Shinmataung and Shwebo Thanaka varieties are the most popular among them. Applying Shwebo Thanaka gives one smooth skin and yellowish beauty unlike Shinmataung Thanaka having a sweet and pleasant smell.

Beyond beauty purposes, the whole Thanaka trees (fruits, root, stem, leaves) have good properties and medicinal benefits. Shwepyinan Company established Thanaka museum in NyaungU city in order to disseminate information of Thanaka culture among young communities and conserve cultural heritage. Myanmar Thanaka Planters and Producers Association was formed on 11 November 2017 in order to safeguard cultural heritage and penetrate Thanaka to international markets and raise public awareness in cooperation with non-governmental organization Helvetas Myanmar.

The association organizes Thanaka beauty pageants, Thanaka trade fair and Myanmar Thanaka Day events to pass Thanaka culture on to the next generation and increase admiration for Thanaka.

Thanaka Day was marked on the full moon day of Tabodwe, connecting Buddhist’s tradition of offering light and Thanaka incense to Buddha. Events related to Thanaka including talk shows, distributing pamphlets, donation and offering Thanaka paste to Buddha are held in the precinct of Pagoda on the Thanaka Day.

The association’s statistics indicated that there are 323,000 acres of Thanaka in Myanmar. The association comprises growers and traders from Ayartaw, Shwebo, Kantbalu, Monywa, Myinmu, Butalin, Kanni, Yinmabin, Pakokku, Myaing, Yesagyo, Pauk, Sittway and Langkho areas and companies from big cities like Yangon, Mandalay and Nay Pyi Taw. Stakeholders involved in the Thanaka supply chain are exerting continuous efforts to produce value-added Thanaka products that were commercially valued in international markets and preserving this heritage and passing it on to future generations through documentation, education, community engagement and revitalization maintaining core values and cultural identity.

Myanmar Thanaka culture has existed for thousands of years. The earliest discovery of applying the Thanaka tradition is back in the Bagan Dynasty. The poems written by King Yazadariz’s sprouse (poet) in 14th century and Shin Ratthasara, monk and prominent poet in 15th century invoked Thanaka culture in literary work.

Furthermore, some communities have traditions of holding the Thanaka Grinding Festival on the first day of the Thingyan Festival and Buddha statues are washed by Thanaka paste, preserving universal value.

Literary works in Bagan, Pyu dynasties captured the essence of Myanmar Thanaka culture, providing a rich source of Thanaka value and traditions of Myanmar people wearing it throughout history.

Inscriptions on Kyaukpyin stone slab note the name of King Bayintnaung’s daughter Princess Dartukalaya, placed at Shwemadaw Pagoda, revealing the solid culture of Thanaka in Taungoo dynasty.

Thanaka supplied to court in King Alaungpaya Dynasty were sourced from Kaput village two miles away from the south of Thihataw Pagoda in KhinU Township, Shwebo District, indicating a notable history of Thanaka again.

Consequently, Myanmar Thanaka that people of all ages and gender cherish and apply to face and body portrayed the significance of the heritage throughout history. Myanmar people are committed to preserving and promoting its culture by holding festivals stimulating community engagement and keeping inventory of Thanaka heritage passing through generations. Literary works and social events describing Myanmar Thanaka tradition act as a window to Myanmar’s intangible cultural heritage. I would like to express my deep respect to those endeavouring to submit nomination of Thanaka as a cultural element by March 2025 to be inscribed on the UNESCO’s list.

If Myanmar’s Thanaka culture and tradition that has dominated for thousand years is recognized and listed by UNESCO, it will be national pride and identity. I hereby would like to appreciate their genuine and continuous efforts with Myanmar Thanaka promotion and cultural awareness campaigns. I am praying from my heart for Myanmar Thanaka to move forward to achieve UNESCO’s inscription.

Translated by KK

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

I read a very interesting topic in the Global New Light of Myanmar newspaper and this topic is preparation for the submission of the Myanma Thanaka cultural tradition to UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity before March 2025, educational programmes on Thanaka culture are being conducted throughout February at museums and libraries under the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture.

I read a very interesting topic in the Global New Light of Myanmar newspaper and this topic is preparation for the submission of the Myanma Thanaka cultural tradition to UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity before March 2025, educational programmes on Thanaka culture are being conducted throughout February at museums and libraries under the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture.

Thanaka is an iconic symbol of Myanmar’s cultural heritage, deeply interlaced into the country’s history, identity, and daily life. For centuries, it has been used as a beauty treatment, sunscreen, and even as a cultural expression of status. The value of Thanaka extends beyond its physical benefits; it holds significant cultural, social, and historical importance to the people of Myanmar. In this essay, we will explore the various dimensions of Thanaka’s value, from its uses in daily life to its role in traditional practices and its symbolic importance.

Historical and Cultural Significance: Thanaka has been a part of Myanmar’s culture for over two thousand years. The tradition of using Thanaka is thought to date back to the Bagan period (around the 11th century AD). It is believed that the earliest use of Thanaka was in the royal courts, where it was applied as a sign of beauty and purity. Over time, this practice spread to all levels of society, and Thanaka became a main feature of Myanmar’s cultural landscape.

The name “Thanaka” refers to the paste made from the powdered bark of the Thanaka tree, which is native to Myanmar and parts of neighbouring Thailand and Laos. The bark is ground into a fine powder, mixed with water, and applied to the face and sometimes the body. The geometric patterns created by the paste are both artistic and practical, reflecting the balance between beauty and function in Myanmar society.

Practical Uses of Thanaka: One of the most important values of Thanaka lies in its practical benefits. It has been used for centuries as a natural skincare product. The paste has cooling properties and helps to protect the skin from the harsh tropical sun, preventing sunburns and skin damage. In a country like Myanmar, where the climate can be extremely hot and sunny, Thanaka serves as an important protective agent against the sun’s ultraviolet rays.

In addition to its sun protection benefits, Thanaka has been credited with having anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anti-ageing properties. It is often used to treat skin conditions like acne, rashes, and blemishes. Many people apply it regularly, not only for its protective effects but also for its potential to improve the skin’s appearance, making it smooth and healthy.

Thanaka’s cooling sensation makes it especially desirable during the summer months. It is common for people, especially women and children, to wear Thanaka as a facial mask to reduce the discomfort of the heat. In rural areas, the tradition of applying Thanaka is especially prevalent, where the natural product is easily accessible and commonly used in everyday life.

Health Benefits of Thanaka: Applied over the cheeks, nose, and neck, Thanaka doubles as both a cosmetic beauty product and a skincare regimen. Marmesin, one of its active ingredients, acts as a natural sunblock against the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays while also providing a refreshing, cooling effect in hot weather.

Symbolic and Social Importance: Thanaka also carries deep symbolic significance. It has become a defining feature of Myanmar’s national identity. When one thinks of the traditional appearance of the Myanmar people, the image of individuals with their faces painted with Thanaka paste is almost universally recognized. This simple yet characteristic practice speaks to a cultural unity that transcends class, gender, and age. In fact, it is a universal symbol of Myanmar’s indigenous heritage, connecting people across generations.

Economic and Environmental Value: Beyond its cultural and social importance, Thanaka also holds economic and environmental value. The production of Thanaka offers economic opportunities for people in rural areas, where Thanaka trees are grown and harvested. Environmentally, the Thanaka tree is also an essential part of the landscape in Myanmar. Thanaka cultivation promotes the growth of trees that provide shade, help preserve biodiversity, and prevent soil erosion. The tree itself is considered a renewable resource, as it can be harvested sustainably, providing both economic and ecological benefits to the local communities.

Moreover, the value of Thanaka in Myanmar is multi-faceted, encompassing its practical benefits for skin care, its role as a cultural and social marker, and its historical and economic importance. This simple paste of powdered bark carries with its centuries of tradition, offering a glimpse into the country’s rich heritage and its deep connection to the natural world. Moreover, Thanaka serves as a protective skincare product, a symbol of beauty, or a reflection of national identity. And it also holds a valuable place in the hearts and minds of the Myanmar people.

References

– Global New Light of Myanmar Newspaper (14 February 2025)

– https://heritage-line.com/magazine/thanaka-the-secret-to-burmese-beauty

– https://myanmartravel.com/thanaka-in-myanmar

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

I read a very interesting topic in the Global New Light of Myanmar newspaper and this topic is preparation for the submission of the Myanma Thanaka cultural tradition to UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity before March 2025, educational programmes on Thanaka culture are being conducted throughout February at museums and libraries under the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture.

Thanaka is an iconic symbol of Myanmar’s cultural heritage, deeply interlaced into the country’s history, identity, and daily life. For centuries, it has been used as a beauty treatment, sunscreen, and even as a cultural expression of status. The value of Thanaka extends beyond its physical benefits; it holds significant cultural, social, and historical importance to the people of Myanmar. In this essay, we will explore the various dimensions of Thanaka’s value, from its uses in daily life to its role in traditional practices and its symbolic importance.

Historical and Cultural Significance: Thanaka has been a part of Myanmar’s culture for over two thousand years. The tradition of using Thanaka is thought to date back to the Bagan period (around the 11th century AD). It is believed that the earliest use of Thanaka was in the royal courts, where it was applied as a sign of beauty and purity. Over time, this practice spread to all levels of society, and Thanaka became a main feature of Myanmar’s cultural landscape.

The name “Thanaka” refers to the paste made from the powdered bark of the Thanaka tree, which is native to Myanmar and parts of neighbouring Thailand and Laos. The bark is ground into a fine powder, mixed with water, and applied to the face and sometimes the body. The geometric patterns created by the paste are both artistic and practical, reflecting the balance between beauty and function in Myanmar society.

Practical Uses of Thanaka: One of the most important values of Thanaka lies in its practical benefits. It has been used for centuries as a natural skincare product. The paste has cooling properties and helps to protect the skin from the harsh tropical sun, preventing sunburns and skin damage. In a country like Myanmar, where the climate can be extremely hot and sunny, Thanaka serves as an important protective agent against the sun’s ultraviolet rays.

In addition to its sun protection benefits, Thanaka has been credited with having anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anti-ageing properties. It is often used to treat skin conditions like acne, rashes, and blemishes. Many people apply it regularly, not only for its protective effects but also for its potential to improve the skin’s appearance, making it smooth and healthy.

Thanaka’s cooling sensation makes it especially desirable during the summer months. It is common for people, especially women and children, to wear Thanaka as a facial mask to reduce the discomfort of the heat. In rural areas, the tradition of applying Thanaka is especially prevalent, where the natural product is easily accessible and commonly used in everyday life.

Health Benefits of Thanaka: Applied over the cheeks, nose, and neck, Thanaka doubles as both a cosmetic beauty product and a skincare regimen. Marmesin, one of its active ingredients, acts as a natural sunblock against the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays while also providing a refreshing, cooling effect in hot weather.

Symbolic and Social Importance: Thanaka also carries deep symbolic significance. It has become a defining feature of Myanmar’s national identity. When one thinks of the traditional appearance of the Myanmar people, the image of individuals with their faces painted with Thanaka paste is almost universally recognized. This simple yet characteristic practice speaks to a cultural unity that transcends class, gender, and age. In fact, it is a universal symbol of Myanmar’s indigenous heritage, connecting people across generations.

Economic and Environmental Value: Beyond its cultural and social importance, Thanaka also holds economic and environmental value. The production of Thanaka offers economic opportunities for people in rural areas, where Thanaka trees are grown and harvested. Environmentally, the Thanaka tree is also an essential part of the landscape in Myanmar. Thanaka cultivation promotes the growth of trees that provide shade, help preserve biodiversity, and prevent soil erosion. The tree itself is considered a renewable resource, as it can be harvested sustainably, providing both economic and ecological benefits to the local communities.

Moreover, the value of Thanaka in Myanmar is multi-faceted, encompassing its practical benefits for skin care, its role as a cultural and social marker, and its historical and economic importance. This simple paste of powdered bark carries with its centuries of tradition, offering a glimpse into the country’s rich heritage and its deep connection to the natural world. Moreover, Thanaka serves as a protective skincare product, a symbol of beauty, or a reflection of national identity. And it also holds a valuable place in the hearts and minds of the Myanmar people.

References

– Global New Light of Myanmar Newspaper (14 February 2025)

– https://heritage-line.com/magazine/thanaka-the-secret-to-burmese-beauty

– https://myanmartravel.com/thanaka-in-myanmar

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

MILLIONS of people from the world including the Chinese dwell in the caves. They lived in the caves for several reasons. No need to pay taxes for the poor people, so they live in the caves. Others dwell on fashion. Over 5,000 years ago in China, Chinese culture started to develop. They dug the sand and created caves in the Yellow River region and lived. Nowadays the people from that region are living in the caves for the cost of cheap. Besides the weather is warm in the winter and cold in the summer.

MILLIONS of people from the world including the Chinese dwell in the caves. They lived in the caves for several reasons. No need to pay taxes for the poor people, so they live in the caves. Others dwell on fashion. Over 5,000 years ago in China, Chinese culture started to develop. They dug the sand and created caves in the Yellow River region and lived. Nowadays the people from that region are living in the caves for the cost of cheap. Besides the weather is warm in the winter and cold in the summer.

Millions of people from the provinces of Shaanxi and Shanxi lived in caves. As the Chinese become rich, they plan to live comfortably in the caves. They decorated the caves with modern precious things. They curved the caves where they lived and sculpted the Buddha stupas in the caves. The amazing sculptures are in Dunhuang, situated in Gansu province. The trains which carried camels, rested in Dunhuang before they went to the Taklamakan Desert. To pay homage that carved the walls of caves, the merchants must pay tax. Colourful wood carvings are beautified in the walls of the cave.

At that time the experts’ sculptures and the art of wood carving had appeared. Plenty of years ago wood carvings were in the caves

and the entrances of caves are covered with sand. In 1920, Aurel Stein from Britain dug this sand. He kept Buddha images and Bibles from the deserts. The visitors from abroad arrived and watched the colourful paintings and wood carvings and bought. So, they acquired a lot of money. The ancient cave is located in Jiaohe, east of China. That cave is near Turpan and it was dug from earth. It has temples, government offices and a jail. Jail is not damaged till nowadays. At this moment the people who live in the caves of China repair the caves to be beautiful and modernized.

The new buildings that are located in the Granada region are worth nearly 100,000 American dollars. On the Sierra Nevada hills that are situated in Guadix, people made caves and about 5,000 people live in these caves. People constructed houses, stores, and hotels in the caves that are located in the North of Spain.

Lately, in the 21st century, more people lived in caves. To prevent heat, people lived in caves at Coober Pedy in Australia. Agates are found in Coober Pedy. People lived in the caves and searched agates. They found agates, so they made a bathroom, and sofa in the living room. About 3000 people lived in Coober. Tourists visited Coober Pedy and excursed under Coober Pedy. They bought agate rings and lockets. The merchants of that city became rich by selling agates. Chinese merchants from Hong Kong made agate rings and lockets and sold them to jewel shops.

There are many famous caves in Myanmar. The most famous cave is the Kaba Aye Cave in Yangon. It is a Sasananika building. The monks teach Bibles to young monks, nuns and people. It is a place of performing good merit. Many donations had done in that cave. In the compound of the cave, there are many buildings of monks to teach the bible.

I and my brother also learned Abhidhamma and other Buddhist languages from Sayadaws. There are many astonished caves in Taunggyi. When I was young, I went with my elder sister and other relatives to Taunggyi.

We visited one of the astonished and fearful caves. Its name is Kyat Cave. It is a big and long cave. Villagers took firesticks and went into the cave. They said that anyone could not go to the end of the cave. The person who tried to go to the end of the cave is not alive. They also told me the exit of the cave was in another country. My elder sister shouted and told me not to see the walls of the cave.

But I looked at the walls of the cave. Oh! How horrible things are curved in the walls of the caves. There are many skulls, witches and devils carved into the walls of the cave. Besides there are many coffins in the cave. Coffins are six feet long. There are many tales about the cave. Alibaba and 500 thieves. The princess and the harpist loving tale. When the king knew his daughter was loved by a harpist and lived in the cave, the angry king closed the entrance of the cave with a rock.

The cave had on existing. They gave their lives for their love. The famous singer Daw Tin Tin Mya sang about that. The title of this song is “Tawagu”. The song is very popular nowadays. Long ago there was a famous cave where 500 bats lived in this cave. When they heard Buddha’s sermons and after they died, they reached the deva. So, we should listen to the sermon. Another famous is Akauk Taung. Akauk Taung is a mountain extending from Pyay District to Hinthada District, renowned for its numerous ancient Buddha images carved into the rock wall along the Ayeyawady River bank. Historically, the mountain served as a tollgate for passing boats and ships. Artisans carved the mountain walls, resulting in 370 Buddha images depicted in various positions standing, sitting and lying.

Most of these Buddha images date back to the Konbaung era, with some originating from the Inwa era. Therefore astonishing, beautiful and fearful caves are around the world. Good people live in the caves to do good things. They pay good benefits for the people and creatures, but bad and wicked people live in the caves to do evil things. They stay in the caves and hide money, and jewels when they get from theft. I pay homage to the Buddha to disappear the worst people from the world, so the people can live safely and peacefully.

Reference: Gimme Shelter, HPH World, 21 June 2007.

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

MILLIONS of people from the world including the Chinese dwell in the caves. They lived in the caves for several reasons. No need to pay taxes for the poor people, so they live in the caves. Others dwell on fashion. Over 5,000 years ago in China, Chinese culture started to develop. They dug the sand and created caves in the Yellow River region and lived. Nowadays the people from that region are living in the caves for the cost of cheap. Besides the weather is warm in the winter and cold in the summer.

Millions of people from the provinces of Shaanxi and Shanxi lived in caves. As the Chinese become rich, they plan to live comfortably in the caves. They decorated the caves with modern precious things. They curved the caves where they lived and sculpted the Buddha stupas in the caves. The amazing sculptures are in Dunhuang, situated in Gansu province. The trains which carried camels, rested in Dunhuang before they went to the Taklamakan Desert. To pay homage that carved the walls of caves, the merchants must pay tax. Colourful wood carvings are beautified in the walls of the cave.

At that time the experts’ sculptures and the art of wood carving had appeared. Plenty of years ago wood carvings were in the caves

and the entrances of caves are covered with sand. In 1920, Aurel Stein from Britain dug this sand. He kept Buddha images and Bibles from the deserts. The visitors from abroad arrived and watched the colourful paintings and wood carvings and bought. So, they acquired a lot of money. The ancient cave is located in Jiaohe, east of China. That cave is near Turpan and it was dug from earth. It has temples, government offices and a jail. Jail is not damaged till nowadays. At this moment the people who live in the caves of China repair the caves to be beautiful and modernized.

The new buildings that are located in the Granada region are worth nearly 100,000 American dollars. On the Sierra Nevada hills that are situated in Guadix, people made caves and about 5,000 people live in these caves. People constructed houses, stores, and hotels in the caves that are located in the North of Spain.

Lately, in the 21st century, more people lived in caves. To prevent heat, people lived in caves at Coober Pedy in Australia. Agates are found in Coober Pedy. People lived in the caves and searched agates. They found agates, so they made a bathroom, and sofa in the living room. About 3000 people lived in Coober. Tourists visited Coober Pedy and excursed under Coober Pedy. They bought agate rings and lockets. The merchants of that city became rich by selling agates. Chinese merchants from Hong Kong made agate rings and lockets and sold them to jewel shops.

There are many famous caves in Myanmar. The most famous cave is the Kaba Aye Cave in Yangon. It is a Sasananika building. The monks teach Bibles to young monks, nuns and people. It is a place of performing good merit. Many donations had done in that cave. In the compound of the cave, there are many buildings of monks to teach the bible.

I and my brother also learned Abhidhamma and other Buddhist languages from Sayadaws. There are many astonished caves in Taunggyi. When I was young, I went with my elder sister and other relatives to Taunggyi.

We visited one of the astonished and fearful caves. Its name is Kyat Cave. It is a big and long cave. Villagers took firesticks and went into the cave. They said that anyone could not go to the end of the cave. The person who tried to go to the end of the cave is not alive. They also told me the exit of the cave was in another country. My elder sister shouted and told me not to see the walls of the cave.

But I looked at the walls of the cave. Oh! How horrible things are curved in the walls of the caves. There are many skulls, witches and devils carved into the walls of the cave. Besides there are many coffins in the cave. Coffins are six feet long. There are many tales about the cave. Alibaba and 500 thieves. The princess and the harpist loving tale. When the king knew his daughter was loved by a harpist and lived in the cave, the angry king closed the entrance of the cave with a rock.

The cave had on existing. They gave their lives for their love. The famous singer Daw Tin Tin Mya sang about that. The title of this song is “Tawagu”. The song is very popular nowadays. Long ago there was a famous cave where 500 bats lived in this cave. When they heard Buddha’s sermons and after they died, they reached the deva. So, we should listen to the sermon. Another famous is Akauk Taung. Akauk Taung is a mountain extending from Pyay District to Hinthada District, renowned for its numerous ancient Buddha images carved into the rock wall along the Ayeyawady River bank. Historically, the mountain served as a tollgate for passing boats and ships. Artisans carved the mountain walls, resulting in 370 Buddha images depicted in various positions standing, sitting and lying.

Most of these Buddha images date back to the Konbaung era, with some originating from the Inwa era. Therefore astonishing, beautiful and fearful caves are around the world. Good people live in the caves to do good things. They pay good benefits for the people and creatures, but bad and wicked people live in the caves to do evil things. They stay in the caves and hide money, and jewels when they get from theft. I pay homage to the Buddha to disappear the worst people from the world, so the people can live safely and peacefully.

Reference: Gimme Shelter, HPH World, 21 June 2007.

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

PYATHO, the 12th month of the Myanmar calendar, brings cool, dew-drenched days. Clematis smilacifolia blooms during this time, infusing the northern air breezes with its fragrant scent.

Farmers harvest the paddy and heap up them in Pyatho. The month also sees bountiful winter crops. The weather is fine and the donation ceremonies are usually held this month. Myanmar people donate the whole year round.

PYATHO, the 12th month of the Myanmar calendar, brings cool, dew-drenched days. Clematis smilacifolia blooms during this time, infusing the northern air breezes with its fragrant scent.

Farmers harvest the paddy and heap up them in Pyatho. The month also sees bountiful winter crops. The weather is fine and the donation ceremonies are usually held this month. Myanmar people donate the whole year round.

Another flower that blooms in Pyatho alongside Clematis smilacifolia is the Bulbophyllum auricomum. This flower is considered the most valuable flora, adorned with various poetic names in U Toe’s poem “Ramayakan”.

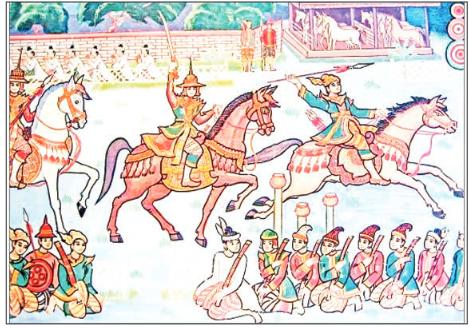

Myanmar’s ancient kings held the equestrian festivals in Pyatho. It was not just a festival, but it also was a competition to select the heroes. According to the ancient Myanmar poem (Trachin) bearing the words “wearing gold embroidery on the waist”, the equestrian festival was held in the reign of Tasishin Thiha Thu during the Pinya era. Moreover, the poem “Myin Saing Shwe Pyi” by Ngasishin Kyaw Swa in the Pinya era featured practice sessions with elephants and horses by the king and his entourage.

Therefore, it can be said that the equestrian festival emerged since then. Heroes were selected based on their elephant and horse-riding skills, and other martial arts.

The equestrian festival requires a space one mile long and two furlongs wide. Additionally, the area includes space for 37 types of horse-riding skills demonstrations and showcases of Myanmar’s martial arts, including Bando and Banshay. A royal tent is erected for the King to enjoy the festivities. To the right of the ring are spear targets at heights of 25, 40, and 60 cubits.

Horse riders must first don their armour and ride skilfully around the ring. Then, they proceed to throw spears at the targets, aiming at the 25-, 40-, and 60-cubit marks step by step.

During the equestrian festival, the royal princes, king’s entourage and subjects can participate in the competitions. The contestants must have special awareness not to lose their hats and Longyis (sarongs for males) during the competitions. If not, he will feel ashamed and it is a sign of their poor skills. The queen and princesses throw their shawls and flowers to the outstanding ones. The outstanding horse rider enters the palace wearing the shawl on his chest and flowers on his ears.

The outstanding horse rider demonstrated his 37 types of horse-riding skills during the spear-throwing event. The leader of the Myanma Hsaing Waing, a traditional Myanmar orchestra under the King’s command, led the Hsaing Waing during the competitions. Heroes were grandly selected, and unique horse-riding champions emerged in Myanmar’s history. During the reign of King Min Khaung of the Inwa era, Thamein Bayan, who triumphed over the Chinese hero Garmani, became a renowned horse-riding hero.

The month of Pyatho is marked by unique festivals and a historic event: the country regained its independence on 4 January 1948 (9th Waning of Pyatho 1309 ME). Consequently, Pyatho is a month that embodies the warlike spirit of independence, along with celebrations of flowers and donation events. — Translated by KTZH

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

PYATHO, the 12th month of the Myanmar calendar, brings cool, dew-drenched days. Clematis smilacifolia blooms during this time, infusing the northern air breezes with its fragrant scent.

Farmers harvest the paddy and heap up them in Pyatho. The month also sees bountiful winter crops. The weather is fine and the donation ceremonies are usually held this month. Myanmar people donate the whole year round.

Another flower that blooms in Pyatho alongside Clematis smilacifolia is the Bulbophyllum auricomum. This flower is considered the most valuable flora, adorned with various poetic names in U Toe’s poem “Ramayakan”.

Myanmar’s ancient kings held the equestrian festivals in Pyatho. It was not just a festival, but it also was a competition to select the heroes. According to the ancient Myanmar poem (Trachin) bearing the words “wearing gold embroidery on the waist”, the equestrian festival was held in the reign of Tasishin Thiha Thu during the Pinya era. Moreover, the poem “Myin Saing Shwe Pyi” by Ngasishin Kyaw Swa in the Pinya era featured practice sessions with elephants and horses by the king and his entourage.

Therefore, it can be said that the equestrian festival emerged since then. Heroes were selected based on their elephant and horse-riding skills, and other martial arts.

The equestrian festival requires a space one mile long and two furlongs wide. Additionally, the area includes space for 37 types of horse-riding skills demonstrations and showcases of Myanmar’s martial arts, including Bando and Banshay. A royal tent is erected for the King to enjoy the festivities. To the right of the ring are spear targets at heights of 25, 40, and 60 cubits.

Horse riders must first don their armour and ride skilfully around the ring. Then, they proceed to throw spears at the targets, aiming at the 25-, 40-, and 60-cubit marks step by step.

During the equestrian festival, the royal princes, king’s entourage and subjects can participate in the competitions. The contestants must have special awareness not to lose their hats and Longyis (sarongs for males) during the competitions. If not, he will feel ashamed and it is a sign of their poor skills. The queen and princesses throw their shawls and flowers to the outstanding ones. The outstanding horse rider enters the palace wearing the shawl on his chest and flowers on his ears.

The outstanding horse rider demonstrated his 37 types of horse-riding skills during the spear-throwing event. The leader of the Myanma Hsaing Waing, a traditional Myanmar orchestra under the King’s command, led the Hsaing Waing during the competitions. Heroes were grandly selected, and unique horse-riding champions emerged in Myanmar’s history. During the reign of King Min Khaung of the Inwa era, Thamein Bayan, who triumphed over the Chinese hero Garmani, became a renowned horse-riding hero.

The month of Pyatho is marked by unique festivals and a historic event: the country regained its independence on 4 January 1948 (9th Waning of Pyatho 1309 ME). Consequently, Pyatho is a month that embodies the warlike spirit of independence, along with celebrations of flowers and donation events. — Translated by KTZH

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

Buddhist Monuments with Circumambulatory Corridors

Buddhist Monuments with Circumambulatory Corridors

In 1873, Alexander Cunningham, a renowned archaeologist and the father of Indian archaeology excavated the Bharhut stupa in Madhya Pradesh, India. This stupa, which is one of the encased stupas in India, was found to have a circumambulatory path. Although smaller than the larger stupas at Sanchi, Bhattiprolu, or Amravati, the Bharhut stupa features remarkable sculptural details. The circumambulatory corridor was designed not only for the act of veneration and circumambulation around the stupa but also to allow observers to appreciate the sculptures and ornamentations as part of the socio-political context.

Similarly, the Dharmarajika stupa in Sarnath reveals six successive encasements through archaeological excavations. Notably, circumambulatory paths (Pradakshina-Patha) were added during the second and third phases of enlargement (Mitra, 1971, pp 66-69). At the Amaravati stupa, a circumambulatory passageway was introduced later, positioned between the railing and the drum of the stupa (Mitra, 1971, pp 200-204).

In contrast, the Phra Pathom stupa in Thailand also features a circumambulatory corridor (see Figure 1). Soni noted that this stupa exemplifies encasement, as a new structure enveloped the original shrine to fulfil King Mongkut’s wish to protect the relics (Soni, 1991). Prior to King Rama IV’s restoration, the Phra Pathom stupa was surmounted by a prang inspired by Khmer Prasat architecture. Following the restoration, King Rama IV’s encasement introduced a gallery path between the older and newly encased outer stupas. These structures include circumambulatory paths designed not only for veneration and movement around the stupa but also for the observation and study of the sculptures and decorations, reflecting their political significance.

Similarly, numerous Moathtaw stupas across Myanmar also feature circumambulatory corridors (Bo Kay, 1981, pp 220- 222). Many of these stupas have stone inscriptions detailing the structures built by King Asoka, providing valuable evidence of the active beliefs during the Bagan era. Some Moathtaw stupas constructed by successive kings are solid, while others are hollow with corridors. At Bagan, three Moathtaw stupas include such corridors. Temple No 1182, a uniquely shaped temple at Bagan, is one example of an encased temple featuring a circumambulatory corridor between its inner and outer structures. These corridors are not only for worship and veneration but also for moving around and studying the art and architecture of the inner and outer stupas, reflecting their socio-political context.

Currently, there are eightythree encased monuments at Bagan, making it the richest area of Buddhist monuments in Myanmar. Most of these encased structures were enlarged by secondary donors to enhance the growth and development of Buddhism and its monuments, emphasizing their socio-political stature and aiming to create stronger, larger, and more durable structures.

Inscribed Relic Caskets

In 1854, Alexander Cunningham discovered several important Buddhist sites, including Sanchi and four nearby sites — Sonari, Satdhara, Morel Khurd, and Andheri — in India, located about 10 kilometres from Sanchi. The inscribed reliquaries from these sites link them to a group of Hemavata teachers led by an individual named Gotiputa. The Hemavata may have arrived in Vidisha during the second century BCE (Sunga period), taking over older sites such as Sanchi and Satdhara while establishing new centres at Sonari, Morel Khurd, and Andheri. Inscribed relic caskets from these sites include relics of Sariputta and Mahamoggallana, chief disciples of the Buddha, which were recovered from Stupa 3 at Sanchi and Stupa 2 at Satdhara (Mitra, 1971, pp 96-99; Shaw et al, 2009). These inscriptions and archaeological findings are significant for understanding the religious and socio-political ideas of the time.

At Bhattiprolu village in the Guntur district of Andhra Pradesh, India, three unexcavated mounds were discovered in 1870. Alexander Rea conducted archaeological excavations at the site in 1892, uncovering three inscribed stone reliquaries containing crystal reliquaries, Buddha’s relics, and jewels. The base of a great stupa, measuring 40 metres in diameter, was recovered at this site. The relics, including a crystal relic casket, were found at the centre of the stupa. Additionally, a silver reliquary, a gold reliquary, a stone receptacle, a copper vessel, and numerous Buddha images were uncovered. Brahmi scripts inscribed on an urn containing Buddha relics were also found. This inscriptional and archaeological evidence highlights the socio-political purposes of enshrining Buddha’s relics, reflecting the donors’ motivations driven by both religious and political concepts. The inscriptions at Bhattiprolu suggest that the relic stupa was intended not only for worship and veneration but also to enhance social and political stature. Bhattiprolu is known for its Buddhist stupa, which was built around the 3rd to 2nd centuries BCE, and the inscriptions indicate that King Kaberuka ruled over Bhattiprolu around 230 BCE. Similarly, the inscribed copper relic casket discovered at Shah-ji-ki-dheri in Peshawar documents the Kushan ruler Kanishka (Mitra, 1971, pp 118-120). An inscribed gilded silver relic casket (see Figure 2) discovered at Khinba mound in 1926-27 mentioned royal donors “Sri Prabhu Varman” and “SriPrabhu Devi”, belonging to the 5th-7th century CE (Varman Dynasty) (Aung Thaw et al, 1993). These inscriptions reflect that many donors were motivated by religious and socio-political concepts, aiming to make the relic-imbued stupa prominent for veneration while also enhancing its associated social and economic benefits.

Inscribed Burial Urns

In 1911-12, four inscribed stone burial urns were discovered 183 metres south of Phayagyi stupa in Sri Kshetra, Myanmar. An additional inscribed stone burial urn (see Figure 3) was found at Payahtaung pagoda in 1993. These inscriptions recorded the royal titles, ages, reigns, and dates of demise of various kings. The urns include names such as “Hrivikrama”, “Sihavikrama”, and “Suravikrama” for the earlier period, and “Devamitra”, “Dhammaditravikrama”, “Brahimhtuvikrama”, “Sihavikrama”, “Suriravikrama”, “Harivikrama”, and “Ardhitravikrama” for the later period, dating to the 7th-8th century CE and reflecting the Vikrama Dynasty. These inscribed burial urns from Sri Kshetra provide significant insights into the socio-political ideas of the time.

In Sri Lanka, the Dekkhina Dagaba (stupa) in Anuradhapura was an encasement and enlargement of an earlier construction built over the ashes of King Duthagamani. Traces of charcoal and ashes found in the centre of the dagaba highlight the significance of this site. Similarly, the Kujjatissa Pabbata (stupa), dating to the 8th century CE and located outside the south gate of the city, contains the ashes of the Elara, buried by King Duthagamani (Ministry of Cultural Affairs, 1981, p 21). These archaeological findings underscore the socio-political importance of burying the ashes of heroic kings in these stupas.

In Thailand, the Royal Chronicles of Ayutthaya (2006) describe the construction of chedis at Wat Phra Si Sanphet. The first chedi, built by King Ramathibodi II (1491-1529 CE) in 1492 CE, enshrined the ashes of his father, King Borommatrailokanat (1448-1463 CE). The second chedi, constructed at the same time, was dedicated to King Borommaracha III (1463- 1488 CE), his elder brother. Forty years later, King Boromracha IV (1529-1533 CE) built the third chedi to enshrine the remains of his father, King Ramathibodi II (Cushman, 2006). The Royal Chronicles also mention that King U Thong (1350-69 CE) arranged for the cremation of two princes, Chao Keo and Chao Thai, and built Wat Pa Kaeo, a stupa, and an assembly hall in their memory. Their ashes may have been enshrined in this stupa. These findings illustrate the religious and socio-political motivations behind enshrining the ashes of heroic kings and royal families in Buddhist monuments across Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Myanmar, highlighting their desire to enhance the social and economic benefits associated with these relic-imbued structures.

Conclusion

The examination of enlarged Buddhist structures, inscribed relic caskets, and burial urns reveals significant socio-political and religious dimensions of Buddhist monument development across South and Southeast Asia. From the early mud stupas of Kapilvastu to the sophisticated encased stupas of Bagan and the circumambulatory corridors found in India, Myanmar and Thailand, these architectural and epigraphic records underscore the integration of religious devotion with socio-political ideologies.

The practice of encasing and enlarging stupas, as seen in the actions of King Uzana in Myanmar and various Indian dynasties, reflects a broader trend where subsequent rulers sought to enhance and preserve earlier structures, aligning their contributions with both religious merit and political stature. Similarly, inscribed relic caskets and burial urns from sites such as Bhattiprolu, Sanchi, and Sri Kshetra provide valuable insights into the motivations behind these monumental acts. They reveal how the veneration of relics and the enshrinement of royal ashes served not only spiritual purposes but also reinforced the socio-political status of the donors.

The inclusion of circumambulatory corridors, as evidenced in the stupas of Bharhut, Dharmarajika, and Phra Pathom, illustrates how architectural modifications were employed to enhance the devotional experience and assert political legitimacy. These corridors facilitated both worship and observation of artistic embellishments, contributing to the stupa’s prominence and durability.

In summary, the study of these Buddhist monuments illustrates how religious practices were intertwined with socio-political objectives. The effort to enlarge these structures and inscribe the relic caskets and burial urns highlights a dynamic interplay between spiritual aspirations and the assertion of political power. This interplay not only reflects the enduring legacy of Buddhist art and architecture but also the ways in which it was employed to reinforce and perpetuate socio-political ideologies across centuries and regions.

References

ASI. (1996). Archaeological Remains, Monuments and Museums, Part-1 & Part-2,

Director General of Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi.

Aung Thaw, U, Myint Aung, Sein Maung Oo and Than Swe. (1993). Shae haung Myanmar myo daw mya [Ancient Myanmar Cities]. Yangon: Ministry of Information.

Bo Kay, U. (1981). Bagan thu te tha na lan nyun [Guide to Bagan Research]. Sapay Beikhman Press, Yangon.

Cushman, Richard D., and David K. Wyatt. (2006). The Royal Chronicles of Ayutthaya.

Bangkok: Siam Society,

DHRNL. (2014). Mandalay Mahamuni dataing awin shi kyauksarmyar (Atwe-Chauk). Stone Inscriptions are located in the walled enclosure of the Mahamuni stupa. Vol-6, Theikpan Press, Mandalay.

Ministry of Cultural Affairs. (1981). A Guide to Anuradhapura, Central Cultural Fund,

Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Mitra, Debala. (1971). Buddhist Monuments. Shishu Sahityu Samsad Pvt. Ld., The India Press Pvt Ld., Calcutta.

Moe (Kyaukse). (2008, May 24). Mandalay Daily: Kyauk sar de ka tha maing [History in the Stone Inscription]. Articles of Makkhaya Shwezigon Stupa

Nan Oo Stupa Stone Inscription. (2007). Nan Oo Phaya Kyauksar. Nan Oo Stupa, Kyaukse Township, Mandalay Region.

Nyein Maung, U. (1972). Shae haung Myanmar kyauk sar myar (Atwe-tit) [Ancient Myanmar Stone Inscriptions (Volume-1)], Yangon: Department of Archaeology.

Nyein Maung, U. (1983). Shae haung Myanmar kyauk sar myar (Atwe-thone) [Ancient Myanmar Stone Inscriptions (Volume-3)], Yangon: Department of Archaeology.

Nyein Maung, U. (1998). Shae haung Myanmar kyauk sar myar (Atwe-lay) [Ancient Myanmar Stone Inscriptions (Volume-4)], Yangon: Department of Archaeology.

Rijal, Babu K. (1979). Archaeological Remains of Kapilvastu, Lumbini, and Devadaha,

Educational Enterprises (PVT) LTD, Kathmandu.

Shaw, Julia, (2009). Stupas, Monasteries and Relics in the Landscape: Typological, Spatial, and Temporal Patterns in the Sanchi Area, Institute of Archaeology, University College London.

Soni, Sujata. (1991). Evolution of Stupas in Burma, Pagan Period: 11th to 13th centuries AD,

Motilal Banarsidass Publishers PVT.LTD, Delhi.

Buddhist Monuments with Circumambulatory Corridors

In 1873, Alexander Cunningham, a renowned archaeologist and the father of Indian archaeology excavated the Bharhut stupa in Madhya Pradesh, India. This stupa, which is one of the encased stupas in India, was found to have a circumambulatory path. Although smaller than the larger stupas at Sanchi, Bhattiprolu, or Amravati, the Bharhut stupa features remarkable sculptural details. The circumambulatory corridor was designed not only for the act of veneration and circumambulation around the stupa but also to allow observers to appreciate the sculptures and ornamentations as part of the socio-political context.

Similarly, the Dharmarajika stupa in Sarnath reveals six successive encasements through archaeological excavations. Notably, circumambulatory paths (Pradakshina-Patha) were added during the second and third phases of enlargement (Mitra, 1971, pp 66-69). At the Amaravati stupa, a circumambulatory passageway was introduced later, positioned between the railing and the drum of the stupa (Mitra, 1971, pp 200-204).

In contrast, the Phra Pathom stupa in Thailand also features a circumambulatory corridor (see Figure 1). Soni noted that this stupa exemplifies encasement, as a new structure enveloped the original shrine to fulfil King Mongkut’s wish to protect the relics (Soni, 1991). Prior to King Rama IV’s restoration, the Phra Pathom stupa was surmounted by a prang inspired by Khmer Prasat architecture. Following the restoration, King Rama IV’s encasement introduced a gallery path between the older and newly encased outer stupas. These structures include circumambulatory paths designed not only for veneration and movement around the stupa but also for the observation and study of the sculptures and decorations, reflecting their political significance.

Similarly, numerous Moathtaw stupas across Myanmar also feature circumambulatory corridors (Bo Kay, 1981, pp 220- 222). Many of these stupas have stone inscriptions detailing the structures built by King Asoka, providing valuable evidence of the active beliefs during the Bagan era. Some Moathtaw stupas constructed by successive kings are solid, while others are hollow with corridors. At Bagan, three Moathtaw stupas include such corridors. Temple No 1182, a uniquely shaped temple at Bagan, is one example of an encased temple featuring a circumambulatory corridor between its inner and outer structures. These corridors are not only for worship and veneration but also for moving around and studying the art and architecture of the inner and outer stupas, reflecting their socio-political context.

Currently, there are eightythree encased monuments at Bagan, making it the richest area of Buddhist monuments in Myanmar. Most of these encased structures were enlarged by secondary donors to enhance the growth and development of Buddhism and its monuments, emphasizing their socio-political stature and aiming to create stronger, larger, and more durable structures.

Inscribed Relic Caskets

In 1854, Alexander Cunningham discovered several important Buddhist sites, including Sanchi and four nearby sites — Sonari, Satdhara, Morel Khurd, and Andheri — in India, located about 10 kilometres from Sanchi. The inscribed reliquaries from these sites link them to a group of Hemavata teachers led by an individual named Gotiputa. The Hemavata may have arrived in Vidisha during the second century BCE (Sunga period), taking over older sites such as Sanchi and Satdhara while establishing new centres at Sonari, Morel Khurd, and Andheri. Inscribed relic caskets from these sites include relics of Sariputta and Mahamoggallana, chief disciples of the Buddha, which were recovered from Stupa 3 at Sanchi and Stupa 2 at Satdhara (Mitra, 1971, pp 96-99; Shaw et al, 2009). These inscriptions and archaeological findings are significant for understanding the religious and socio-political ideas of the time.

At Bhattiprolu village in the Guntur district of Andhra Pradesh, India, three unexcavated mounds were discovered in 1870. Alexander Rea conducted archaeological excavations at the site in 1892, uncovering three inscribed stone reliquaries containing crystal reliquaries, Buddha’s relics, and jewels. The base of a great stupa, measuring 40 metres in diameter, was recovered at this site. The relics, including a crystal relic casket, were found at the centre of the stupa. Additionally, a silver reliquary, a gold reliquary, a stone receptacle, a copper vessel, and numerous Buddha images were uncovered. Brahmi scripts inscribed on an urn containing Buddha relics were also found. This inscriptional and archaeological evidence highlights the socio-political purposes of enshrining Buddha’s relics, reflecting the donors’ motivations driven by both religious and political concepts. The inscriptions at Bhattiprolu suggest that the relic stupa was intended not only for worship and veneration but also to enhance social and political stature. Bhattiprolu is known for its Buddhist stupa, which was built around the 3rd to 2nd centuries BCE, and the inscriptions indicate that King Kaberuka ruled over Bhattiprolu around 230 BCE. Similarly, the inscribed copper relic casket discovered at Shah-ji-ki-dheri in Peshawar documents the Kushan ruler Kanishka (Mitra, 1971, pp 118-120). An inscribed gilded silver relic casket (see Figure 2) discovered at Khinba mound in 1926-27 mentioned royal donors “Sri Prabhu Varman” and “SriPrabhu Devi”, belonging to the 5th-7th century CE (Varman Dynasty) (Aung Thaw et al, 1993). These inscriptions reflect that many donors were motivated by religious and socio-political concepts, aiming to make the relic-imbued stupa prominent for veneration while also enhancing its associated social and economic benefits.

Inscribed Burial Urns

In 1911-12, four inscribed stone burial urns were discovered 183 metres south of Phayagyi stupa in Sri Kshetra, Myanmar. An additional inscribed stone burial urn (see Figure 3) was found at Payahtaung pagoda in 1993. These inscriptions recorded the royal titles, ages, reigns, and dates of demise of various kings. The urns include names such as “Hrivikrama”, “Sihavikrama”, and “Suravikrama” for the earlier period, and “Devamitra”, “Dhammaditravikrama”, “Brahimhtuvikrama”, “Sihavikrama”, “Suriravikrama”, “Harivikrama”, and “Ardhitravikrama” for the later period, dating to the 7th-8th century CE and reflecting the Vikrama Dynasty. These inscribed burial urns from Sri Kshetra provide significant insights into the socio-political ideas of the time.

In Sri Lanka, the Dekkhina Dagaba (stupa) in Anuradhapura was an encasement and enlargement of an earlier construction built over the ashes of King Duthagamani. Traces of charcoal and ashes found in the centre of the dagaba highlight the significance of this site. Similarly, the Kujjatissa Pabbata (stupa), dating to the 8th century CE and located outside the south gate of the city, contains the ashes of the Elara, buried by King Duthagamani (Ministry of Cultural Affairs, 1981, p 21). These archaeological findings underscore the socio-political importance of burying the ashes of heroic kings in these stupas.

In Thailand, the Royal Chronicles of Ayutthaya (2006) describe the construction of chedis at Wat Phra Si Sanphet. The first chedi, built by King Ramathibodi II (1491-1529 CE) in 1492 CE, enshrined the ashes of his father, King Borommatrailokanat (1448-1463 CE). The second chedi, constructed at the same time, was dedicated to King Borommaracha III (1463- 1488 CE), his elder brother. Forty years later, King Boromracha IV (1529-1533 CE) built the third chedi to enshrine the remains of his father, King Ramathibodi II (Cushman, 2006). The Royal Chronicles also mention that King U Thong (1350-69 CE) arranged for the cremation of two princes, Chao Keo and Chao Thai, and built Wat Pa Kaeo, a stupa, and an assembly hall in their memory. Their ashes may have been enshrined in this stupa. These findings illustrate the religious and socio-political motivations behind enshrining the ashes of heroic kings and royal families in Buddhist monuments across Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Myanmar, highlighting their desire to enhance the social and economic benefits associated with these relic-imbued structures.

Conclusion

The examination of enlarged Buddhist structures, inscribed relic caskets, and burial urns reveals significant socio-political and religious dimensions of Buddhist monument development across South and Southeast Asia. From the early mud stupas of Kapilvastu to the sophisticated encased stupas of Bagan and the circumambulatory corridors found in India, Myanmar and Thailand, these architectural and epigraphic records underscore the integration of religious devotion with socio-political ideologies.

The practice of encasing and enlarging stupas, as seen in the actions of King Uzana in Myanmar and various Indian dynasties, reflects a broader trend where subsequent rulers sought to enhance and preserve earlier structures, aligning their contributions with both religious merit and political stature. Similarly, inscribed relic caskets and burial urns from sites such as Bhattiprolu, Sanchi, and Sri Kshetra provide valuable insights into the motivations behind these monumental acts. They reveal how the veneration of relics and the enshrinement of royal ashes served not only spiritual purposes but also reinforced the socio-political status of the donors.

The inclusion of circumambulatory corridors, as evidenced in the stupas of Bharhut, Dharmarajika, and Phra Pathom, illustrates how architectural modifications were employed to enhance the devotional experience and assert political legitimacy. These corridors facilitated both worship and observation of artistic embellishments, contributing to the stupa’s prominence and durability.

In summary, the study of these Buddhist monuments illustrates how religious practices were intertwined with socio-political objectives. The effort to enlarge these structures and inscribe the relic caskets and burial urns highlights a dynamic interplay between spiritual aspirations and the assertion of political power. This interplay not only reflects the enduring legacy of Buddhist art and architecture but also the ways in which it was employed to reinforce and perpetuate socio-political ideologies across centuries and regions.

References

ASI. (1996). Archaeological Remains, Monuments and Museums, Part-1 & Part-2,

Director General of Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi.

Aung Thaw, U, Myint Aung, Sein Maung Oo and Than Swe. (1993). Shae haung Myanmar myo daw mya [Ancient Myanmar Cities]. Yangon: Ministry of Information.

Bo Kay, U. (1981). Bagan thu te tha na lan nyun [Guide to Bagan Research]. Sapay Beikhman Press, Yangon.

Cushman, Richard D., and David K. Wyatt. (2006). The Royal Chronicles of Ayutthaya.

Bangkok: Siam Society,

DHRNL. (2014). Mandalay Mahamuni dataing awin shi kyauksarmyar (Atwe-Chauk). Stone Inscriptions are located in the walled enclosure of the Mahamuni stupa. Vol-6, Theikpan Press, Mandalay.

Ministry of Cultural Affairs. (1981). A Guide to Anuradhapura, Central Cultural Fund,

Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Mitra, Debala. (1971). Buddhist Monuments. Shishu Sahityu Samsad Pvt. Ld., The India Press Pvt Ld., Calcutta.

Moe (Kyaukse). (2008, May 24). Mandalay Daily: Kyauk sar de ka tha maing [History in the Stone Inscription]. Articles of Makkhaya Shwezigon Stupa

Nan Oo Stupa Stone Inscription. (2007). Nan Oo Phaya Kyauksar. Nan Oo Stupa, Kyaukse Township, Mandalay Region.

Nyein Maung, U. (1972). Shae haung Myanmar kyauk sar myar (Atwe-tit) [Ancient Myanmar Stone Inscriptions (Volume-1)], Yangon: Department of Archaeology.

Nyein Maung, U. (1983). Shae haung Myanmar kyauk sar myar (Atwe-thone) [Ancient Myanmar Stone Inscriptions (Volume-3)], Yangon: Department of Archaeology.

Nyein Maung, U. (1998). Shae haung Myanmar kyauk sar myar (Atwe-lay) [Ancient Myanmar Stone Inscriptions (Volume-4)], Yangon: Department of Archaeology.

Rijal, Babu K. (1979). Archaeological Remains of Kapilvastu, Lumbini, and Devadaha,

Educational Enterprises (PVT) LTD, Kathmandu.

Shaw, Julia, (2009). Stupas, Monasteries and Relics in the Landscape: Typological, Spatial, and Temporal Patterns in the Sanchi Area, Institute of Archaeology, University College London.

Soni, Sujata. (1991). Evolution of Stupas in Burma, Pagan Period: 11th to 13th centuries AD,

Motilal Banarsidass Publishers PVT.LTD, Delhi.

Introduction