Myanmar women have preserved the noble traditions and customs from generation to generation. The efforts of these women in safeguarding such traditions are also prominently reflected in the literature that emerged across different eras.

Myanmar women have preserved the noble traditions and customs from generation to generation. The efforts of these women in safeguarding such traditions are also prominently reflected in the literature that emerged across different eras.

According to the 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census, number of women accounted for approximately 29.4 million out of the total population of around 56.2 million, indicating that more than half of the country’s population is women. Being a Union made up of over 100 different ethnic groups, Myanmar is home to a wide diversity of traditional cultures, customs, languages, dress, historical backgrounds, and geographical features.

In the present day, Myanmar women not only shoulder the traditional role of household responsibilities, but also keep abreast with men in contributing to both personal and social progress. As women are considered a vulnerable group, it is essential to protect and nurture their lives, ensuring their well-being and empowerment. At the same time, their rights and livelihoods must be safeguarded and promoted, particularly in the areas of education, healthcare, economy, social development, and overall security for young women. Women themselves must also strive to preserve and uphold the dignity and value of womanhood.

An important aspect for Myanmar women is the preservation of their ethnic traditions, cultural customs, national pride, and dignity. These values must be safeguarded to ensure that they are neither diminished nor lost. Therefore, it is essential to continuously foster a mindset that cherishes and values the lives of women, promoting a spirit of respect, pride, and cultural identity throughout their lives. Myanmar people should know their tradition and culture and should not value others’ cultures while preserving their tradition and culture, and this includes traditional dress and customs.

Myanmar girls and women wore traditional garments such as Yin Phone and longyi, following the attitudes of their parents. They gracefully wear Myanmar traditional dress at religious events, pagoda festivals and donation events. However, some young people may be considered reckless for wearing skirts, shorts and long pants in ways that may damage Myanmar culture.

Myanmar women are the rising stars of the future, and they should wear safe and fine dresses as they are living in a country with the proclamation of Buddhism. Moreover, they can be known as Myanmar by the tourists whenever they see them wearing a Myanmar dress.

Myanmar girls serve as role models in preserving traditional cultural heritage by wearing Yin Phone and longyi. Naturally calm and composed, Myanmar women are also known for their gentle and graceful demeanour, which contributes to their dignified feminine charm.

Therefore, from major cities to rural areas, Myanmar’s traditional cultural heritage should be preserved. The beauty of traditional attire and customs, which deserves to be honoured as a form of cultural art, should be portrayed by artists as a masterpiece delicately painted with the skilled brushstrokes of Myanmar culture.

Just as Myanmar women rightfully possess the tradition of wearing cultural attire, they should also uphold modesty and a sense of decency in how they dress. Their clothing should be neither too plain nor overly extravagant, neither outdated nor excessively modern. By wearing traditional Myanmar dress, which is most pleasing to the eye, heartwarming to the soul, and rich in elegance and dignity, they help preserve the beauty and cultural heritage of Myanmar women today and pass it down as a cherished legacy to future generations of young girls. This article is created in honour of the Myanmar Women’s Day, which will fall on 3 July 2025.

Translated by KTZH

Source: GNLM

Myanmar women have preserved the noble traditions and customs from generation to generation. The efforts of these women in safeguarding such traditions are also prominently reflected in the literature that emerged across different eras.

According to the 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census, number of women accounted for approximately 29.4 million out of the total population of around 56.2 million, indicating that more than half of the country’s population is women. Being a Union made up of over 100 different ethnic groups, Myanmar is home to a wide diversity of traditional cultures, customs, languages, dress, historical backgrounds, and geographical features.

In the present day, Myanmar women not only shoulder the traditional role of household responsibilities, but also keep abreast with men in contributing to both personal and social progress. As women are considered a vulnerable group, it is essential to protect and nurture their lives, ensuring their well-being and empowerment. At the same time, their rights and livelihoods must be safeguarded and promoted, particularly in the areas of education, healthcare, economy, social development, and overall security for young women. Women themselves must also strive to preserve and uphold the dignity and value of womanhood.

An important aspect for Myanmar women is the preservation of their ethnic traditions, cultural customs, national pride, and dignity. These values must be safeguarded to ensure that they are neither diminished nor lost. Therefore, it is essential to continuously foster a mindset that cherishes and values the lives of women, promoting a spirit of respect, pride, and cultural identity throughout their lives. Myanmar people should know their tradition and culture and should not value others’ cultures while preserving their tradition and culture, and this includes traditional dress and customs.

Myanmar girls and women wore traditional garments such as Yin Phone and longyi, following the attitudes of their parents. They gracefully wear Myanmar traditional dress at religious events, pagoda festivals and donation events. However, some young people may be considered reckless for wearing skirts, shorts and long pants in ways that may damage Myanmar culture.

Myanmar women are the rising stars of the future, and they should wear safe and fine dresses as they are living in a country with the proclamation of Buddhism. Moreover, they can be known as Myanmar by the tourists whenever they see them wearing a Myanmar dress.

Myanmar girls serve as role models in preserving traditional cultural heritage by wearing Yin Phone and longyi. Naturally calm and composed, Myanmar women are also known for their gentle and graceful demeanour, which contributes to their dignified feminine charm.

Therefore, from major cities to rural areas, Myanmar’s traditional cultural heritage should be preserved. The beauty of traditional attire and customs, which deserves to be honoured as a form of cultural art, should be portrayed by artists as a masterpiece delicately painted with the skilled brushstrokes of Myanmar culture.

Just as Myanmar women rightfully possess the tradition of wearing cultural attire, they should also uphold modesty and a sense of decency in how they dress. Their clothing should be neither too plain nor overly extravagant, neither outdated nor excessively modern. By wearing traditional Myanmar dress, which is most pleasing to the eye, heartwarming to the soul, and rich in elegance and dignity, they help preserve the beauty and cultural heritage of Myanmar women today and pass it down as a cherished legacy to future generations of young girls. This article is created in honour of the Myanmar Women’s Day, which will fall on 3 July 2025.

Translated by KTZH

Source: GNLM

Evolution of Yoga

Yoga’s history is deeply rooted in ancient India, with origins possibly dating back over 5,000 years to the Indus-Sarasvati civilization. The earliest written records appear in the Vedic texts, around 1500 BCE. Over time, Yoga evolved into a system of physical, mental and spiritual practices, passed down through generations. Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, around 200 BCE, provided a comprehensive framework, including the Eight Limbs of Yoga, which are still relevant today. The classical form of Yoga, as outlined by Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras, is known as Ashtanga Yoga, also referred to as Raja Yoga or the Eight-Limbed Path. It’s a holistic system encompassing physical, mental and spiritual practices, aiming for self-realization.

These eight limbs of Ashtanga Yoga are:

1. Yama: Ethical guidelines and restraints.

2. Niyama: Self-disciplinary practices.

3. Asana: Physical postures.

4. Pranayama: Breath control techniques.

5. Pratyahara: Withdrawal of senses from the external world.

6. Dharana: Concentration.

7. Dhyana: Meditation.

8. Samadhi: State of absorption or union with the divine.

In contemporary Bharat, several figures have significantly developed the understanding and practice of Yoga from ancient traditions, while also adapting them to modern contexts. Some prominent names include Swami Vivekananda, Sri Aurobindo, B K S Iyengar, Sri Ravi Shankar and so on. Swami Vivekananda is widely regarded as a key architect of the revival of Yoga in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He brought the philosophy and practices of Yoga to the West, introducing it to a broader audience and emphasizing its practical aspects for spiritual growth and social reform. His speeches and writings, particularly his 1893 address at the World’s Parliament of Religions, were remarkable. He also developed his own interpretations of Yoga, incorporating elements of Vedanta and other Hindu philosophies. He presented four distinct yet interconnected paths of Yogas, towards spiritual realization and self-discovery: Karma Yoga (the path of action), Bhakti Yoga (the path of devotion). Raja Yoga (the path of concentration and discipline) and Jnana Yoga (the path of knowledge). Each yoga has a unique approach to realizing the divine within, and Vivekananda believed that all four are equally valid paths to enlightenment.

Sri Aurobindo’s “Integral Yoga” offered a comprehensive approach to spiritual evolution, encompassing physical, mental and spiritual development. He integrated Yoga with his larger philosophy of human evolution and the development of a higher consciousness.

With time, many thinkers, philosophers and teachers propagated and promoted Yoga across the Globe with their unique styles. Society values its importance in its day-to-day life.

Impact of Yoga on Well-being

Yoga has significantly evolved and become a prominent part of contemporary wellness practices, moving beyond its traditional roots to encompass diverse styles and applications, each offering unique benefits and approaches. Some of the most common types include Hatha Yoga, Vinyasa, Ashtanga Yoga, Mantra Yoga, Kriya Yoga and so on. These styles differ in their focus on physical postures, breathwork, meditation and energy flow. It’s increasingly recognized for its benefits in stress reduction, promoting mental and physical health and fostering a sense of balance and well-being. Modern Yoga is also integrated into various settings, including schools, corporations and healthcare systems, reflecting its growing relevance in addressing the needs of the modern world.

Yoga is important because it offers numerous physical, mental and emotional benefits, improving overall well-being and promoting a healthier lifestyle. It’s a practice that can help individuals manage stress, enhance flexibility and strength and even improve sleep quality.

The numerous benefits of Yoga offer a holistic development of an individual in the following way:

Physiological Benefits:

• Improved Flexibility and Strength:

Yoga poses (asanas) target various muscle groups, enhancing flexibility and building strength.

• Reduced Risk of Injury:

Increased flexibility and body awareness can help prevent injuries, especially in sports and other physical activities.

• Better Posture and Balance:

Yoga can improve posture, balance and coordination, leading to physiological benefits like better body alignment and stability.

• Improved Cardiovascular Health:

Regular Yoga practice can help lower blood pressure and heart rate, potentially reducing the risk of heart disease.

• Pain Management:

Yoga can be effective in managing various types of chronic pain, such as back pain and arthritis.

Psychological and Emotional Gains:

• Stress Reduction:

Yoga’s emphasis on breathing and mindfulness can help calm the mind and reduce stress hormones.

• Improved Sleep:

Yoga can help relax the body and mind, making it easier to fall asleep and stay asleep.

• Enhanced Mental Clarity and Focus:

Yoga can improve concentration and attention, leading to better cognitive function.

• Emotional Regulation:

Yoga can help individuals become more aware of their emotions and develop healthy coping mechanisms.

• Increased Mindfulness and Self-Awareness:

Yoga fosters a sense of being present in the moment, which can lead to greater self-awareness and improved decision-making.

Path to Inner Awakening:

• Connection to Self and Others:

Yoga encourages a deeper understanding of oneself and one’s place in the world, promoting a sense of inter connectedness.

• Cultivation of Inner Peace and Harmony:

Yoga can help individuals find inner peace and cultivate a sense of balance and harmony in their lives.

Therefore, Yoga is a valuable practice that can enhance physical, mental, and emotional well-being. Its benefits extend beyond physical exercise, offering a holistic approach to health and wellness. It helps an individual to grow and nurture from the Gross to the subtle.

Yoga and Myanmar: The Connection

Yoga has a deep connection with Myanmar’s cultural landscape due to the shared. historical ties with India, where Yoga originated. Myanmar, the land of meditation, emphasizes mindfulness, inner peace and self-discipline. Yoga is becoming increasingly popular in Myanmar, with a number of Yoga studios and centres opening in different cities like Yangon, Bago, Nay Pyi Taw, Bagan, Mandalay, Sittway, etc.

Myanmar is my fourth posting from the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) & the Ministry of External Affairs to promote Yoga. The previous countries included- Hungary, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Cambodia, and New Zealand. I have noticed that the people of Myanmar have a keen interest in knowing the Classical form of Yoga from the Yoga texts. Like any other country, they have a deep interest in staying healthy and active. More than 200 Yoga enthusiasts have joined my Yoga classes at the SVCC, Embassy of India in Yangon. The beautiful parks and gardens across Yangon, like Mahabandoola Park, People’s Park, and Kandawgyi Lake, offer an interesting and fresh atmosphere for fitness enthusiasts to practise Yoga, Pilates, Zumba and other healthy activities in large groups. The serene atmosphere in pagodas like Sule Pagoda and Shwedagon Pagoda allows the local people of Myanmar to disconnect from the outside world and connect with the Self. These strong techniques help the local people to balance their thoughts and emotions to face the different problems and situations of life.

As Buddhism spread from India to Myanmar, it carried forward techniques of mindfulness and concentration that complement the science of Yoga. In essence, meditation serves as a profound path to cultivate mindfulness, inner awareness and overall well-being. Yoga evolved as a system for self-realization during the Vedic period, while meditation practices gained prominence with the rise of Buddhism. Both Yoga and meditation in Myanmar emphasize cultivating mindfulness and deep inner awareness. In Yoga, mindfulness is developed through postures, breath control, and meditation, fostering a connection between the body and mind. Similarly, meditation practices in Myanmar, such as Vipassana (insight meditation), centre on observing the present moment with clarity and understanding the true nature of reality. Yoga in Myanmar is gaining popularity as Myanmar’s predominantly Buddhist culture provides a unique context for Yoga practice, with opportunities to integrate Yoga with meditation and spiritual practice. The Embassy of India (SVCC) in Yangon has organized several International Yoga Day celebrations across the country, and many health enthusiasts actively participate in these initiatives. This year, we are celebrating the 11th International Day of Yoga 2025 with the theme “Yoga for One Earth, One Health”, which highlights Yoga’s role in promoting physical, mental and environmental well-being, aligning with global calls for sustainability and unity. The Embassy of India is planning different events to celebrate this year’s International Day of Yoga.

Significance of Yoga for the people of Myanmar

Yoga is gaining significance in Myanmar as a tool for physical and mental well-being, offering benefits like stress reduction, improved flexibility and a deeper connection to the body and mind. It is a way to promote health, prevent disease and cultivate inner peace, aligning with Myanmar’s Buddhist traditions and emphasis on mindfulness. The following are the key benefits which individuals are experiencing in different dimensions:

• Physical Dimension:

Yoga practices can improve physical health by increasing flexibility, strength, and balance. They can also help with managing stress, which is a major factor in many lifestyle-related disorders.

• Mental Dimension:

Yoga’s emphasis on mindfulness and meditation can help reduce stress, anxiety, and depression. It promotes a sense of calm and inner peace, which can be particularly beneficial in a society that values spiritual well-being.

• Spiritual Dimension:

Yoga’s roots, in ancient Indian traditions, including its focus on self-discipline and inner awareness, connect well with Myanmar’s Buddhist culture and its emphasis on meditation and mindfulness. Yoga can deepen understanding of the nature of life and cultivate inner peace, which is valued in Myanmar’s spiritual traditions.

• Social and Cultural Significance:

Yoga is increasingly being recognized as a practice that can promote harmony and well-being in all aspects of life. It’s also becoming a more accessible practice, with yoga studios and instructors becoming more common in Myanmar.

International Recognition:

The celebration of the International Day of Yoga in Myanmar highlights its growing significance and the global recognition of its benefits.

Yoga is therefore gaining popularity in Myanmar and is viewed as a way to promote physical, mental and spiritual well-being. It is often practised in conjunction with meditation, reflecting the influence of Buddhism in the country. Yoga studios and retreats are becoming more common, offering a variety of classes and workshops for different levels of practitioners.

My personal experience in Myanmar so far is a blend of ancient history, vibrant culture, and natural beauty, but the best part about Myanmar is its beautiful people. The love and warmth which I receive from my Yoga students is overwhelming.

GNLM

Evolution of Yoga

Yoga’s history is deeply rooted in ancient India, with origins possibly dating back over 5,000 years to the Indus-Sarasvati civilization. The earliest written records appear in the Vedic texts, around 1500 BCE. Over time, Yoga evolved into a system of physical, mental and spiritual practices, passed down through generations. Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, around 200 BCE, provided a comprehensive framework, including the Eight Limbs of Yoga, which are still relevant today. The classical form of Yoga, as outlined by Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras, is known as Ashtanga Yoga, also referred to as Raja Yoga or the Eight-Limbed Path. It’s a holistic system encompassing physical, mental and spiritual practices, aiming for self-realization.

These eight limbs of Ashtanga Yoga are:

1. Yama: Ethical guidelines and restraints.

2. Niyama: Self-disciplinary practices.

3. Asana: Physical postures.

4. Pranayama: Breath control techniques.

5. Pratyahara: Withdrawal of senses from the external world.

6. Dharana: Concentration.

7. Dhyana: Meditation.

8. Samadhi: State of absorption or union with the divine.

In contemporary Bharat, several figures have significantly developed the understanding and practice of Yoga from ancient traditions, while also adapting them to modern contexts. Some prominent names include Swami Vivekananda, Sri Aurobindo, B K S Iyengar, Sri Ravi Shankar and so on. Swami Vivekananda is widely regarded as a key architect of the revival of Yoga in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He brought the philosophy and practices of Yoga to the West, introducing it to a broader audience and emphasizing its practical aspects for spiritual growth and social reform. His speeches and writings, particularly his 1893 address at the World’s Parliament of Religions, were remarkable. He also developed his own interpretations of Yoga, incorporating elements of Vedanta and other Hindu philosophies. He presented four distinct yet interconnected paths of Yogas, towards spiritual realization and self-discovery: Karma Yoga (the path of action), Bhakti Yoga (the path of devotion). Raja Yoga (the path of concentration and discipline) and Jnana Yoga (the path of knowledge). Each yoga has a unique approach to realizing the divine within, and Vivekananda believed that all four are equally valid paths to enlightenment.

Sri Aurobindo’s “Integral Yoga” offered a comprehensive approach to spiritual evolution, encompassing physical, mental and spiritual development. He integrated Yoga with his larger philosophy of human evolution and the development of a higher consciousness.

With time, many thinkers, philosophers and teachers propagated and promoted Yoga across the Globe with their unique styles. Society values its importance in its day-to-day life.

Impact of Yoga on Well-being

Yoga has significantly evolved and become a prominent part of contemporary wellness practices, moving beyond its traditional roots to encompass diverse styles and applications, each offering unique benefits and approaches. Some of the most common types include Hatha Yoga, Vinyasa, Ashtanga Yoga, Mantra Yoga, Kriya Yoga and so on. These styles differ in their focus on physical postures, breathwork, meditation and energy flow. It’s increasingly recognized for its benefits in stress reduction, promoting mental and physical health and fostering a sense of balance and well-being. Modern Yoga is also integrated into various settings, including schools, corporations and healthcare systems, reflecting its growing relevance in addressing the needs of the modern world.

Yoga is important because it offers numerous physical, mental and emotional benefits, improving overall well-being and promoting a healthier lifestyle. It’s a practice that can help individuals manage stress, enhance flexibility and strength and even improve sleep quality.

The numerous benefits of Yoga offer a holistic development of an individual in the following way:

Physiological Benefits:

• Improved Flexibility and Strength:

Yoga poses (asanas) target various muscle groups, enhancing flexibility and building strength.

• Reduced Risk of Injury:

Increased flexibility and body awareness can help prevent injuries, especially in sports and other physical activities.

• Better Posture and Balance:

Yoga can improve posture, balance and coordination, leading to physiological benefits like better body alignment and stability.

• Improved Cardiovascular Health:

Regular Yoga practice can help lower blood pressure and heart rate, potentially reducing the risk of heart disease.

• Pain Management:

Yoga can be effective in managing various types of chronic pain, such as back pain and arthritis.

Psychological and Emotional Gains:

• Stress Reduction:

Yoga’s emphasis on breathing and mindfulness can help calm the mind and reduce stress hormones.

• Improved Sleep:

Yoga can help relax the body and mind, making it easier to fall asleep and stay asleep.

• Enhanced Mental Clarity and Focus:

Yoga can improve concentration and attention, leading to better cognitive function.

• Emotional Regulation:

Yoga can help individuals become more aware of their emotions and develop healthy coping mechanisms.

• Increased Mindfulness and Self-Awareness:

Yoga fosters a sense of being present in the moment, which can lead to greater self-awareness and improved decision-making.

Path to Inner Awakening:

• Connection to Self and Others:

Yoga encourages a deeper understanding of oneself and one’s place in the world, promoting a sense of inter connectedness.

• Cultivation of Inner Peace and Harmony:

Yoga can help individuals find inner peace and cultivate a sense of balance and harmony in their lives.

Therefore, Yoga is a valuable practice that can enhance physical, mental, and emotional well-being. Its benefits extend beyond physical exercise, offering a holistic approach to health and wellness. It helps an individual to grow and nurture from the Gross to the subtle.

Yoga and Myanmar: The Connection

Yoga has a deep connection with Myanmar’s cultural landscape due to the shared. historical ties with India, where Yoga originated. Myanmar, the land of meditation, emphasizes mindfulness, inner peace and self-discipline. Yoga is becoming increasingly popular in Myanmar, with a number of Yoga studios and centres opening in different cities like Yangon, Bago, Nay Pyi Taw, Bagan, Mandalay, Sittway, etc.

Myanmar is my fourth posting from the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) & the Ministry of External Affairs to promote Yoga. The previous countries included- Hungary, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Cambodia, and New Zealand. I have noticed that the people of Myanmar have a keen interest in knowing the Classical form of Yoga from the Yoga texts. Like any other country, they have a deep interest in staying healthy and active. More than 200 Yoga enthusiasts have joined my Yoga classes at the SVCC, Embassy of India in Yangon. The beautiful parks and gardens across Yangon, like Mahabandoola Park, People’s Park, and Kandawgyi Lake, offer an interesting and fresh atmosphere for fitness enthusiasts to practise Yoga, Pilates, Zumba and other healthy activities in large groups. The serene atmosphere in pagodas like Sule Pagoda and Shwedagon Pagoda allows the local people of Myanmar to disconnect from the outside world and connect with the Self. These strong techniques help the local people to balance their thoughts and emotions to face the different problems and situations of life.

As Buddhism spread from India to Myanmar, it carried forward techniques of mindfulness and concentration that complement the science of Yoga. In essence, meditation serves as a profound path to cultivate mindfulness, inner awareness and overall well-being. Yoga evolved as a system for self-realization during the Vedic period, while meditation practices gained prominence with the rise of Buddhism. Both Yoga and meditation in Myanmar emphasize cultivating mindfulness and deep inner awareness. In Yoga, mindfulness is developed through postures, breath control, and meditation, fostering a connection between the body and mind. Similarly, meditation practices in Myanmar, such as Vipassana (insight meditation), centre on observing the present moment with clarity and understanding the true nature of reality. Yoga in Myanmar is gaining popularity as Myanmar’s predominantly Buddhist culture provides a unique context for Yoga practice, with opportunities to integrate Yoga with meditation and spiritual practice. The Embassy of India (SVCC) in Yangon has organized several International Yoga Day celebrations across the country, and many health enthusiasts actively participate in these initiatives. This year, we are celebrating the 11th International Day of Yoga 2025 with the theme “Yoga for One Earth, One Health”, which highlights Yoga’s role in promoting physical, mental and environmental well-being, aligning with global calls for sustainability and unity. The Embassy of India is planning different events to celebrate this year’s International Day of Yoga.

Significance of Yoga for the people of Myanmar

Yoga is gaining significance in Myanmar as a tool for physical and mental well-being, offering benefits like stress reduction, improved flexibility and a deeper connection to the body and mind. It is a way to promote health, prevent disease and cultivate inner peace, aligning with Myanmar’s Buddhist traditions and emphasis on mindfulness. The following are the key benefits which individuals are experiencing in different dimensions:

• Physical Dimension:

Yoga practices can improve physical health by increasing flexibility, strength, and balance. They can also help with managing stress, which is a major factor in many lifestyle-related disorders.

• Mental Dimension:

Yoga’s emphasis on mindfulness and meditation can help reduce stress, anxiety, and depression. It promotes a sense of calm and inner peace, which can be particularly beneficial in a society that values spiritual well-being.

• Spiritual Dimension:

Yoga’s roots, in ancient Indian traditions, including its focus on self-discipline and inner awareness, connect well with Myanmar’s Buddhist culture and its emphasis on meditation and mindfulness. Yoga can deepen understanding of the nature of life and cultivate inner peace, which is valued in Myanmar’s spiritual traditions.

• Social and Cultural Significance:

Yoga is increasingly being recognized as a practice that can promote harmony and well-being in all aspects of life. It’s also becoming a more accessible practice, with yoga studios and instructors becoming more common in Myanmar.

International Recognition:

The celebration of the International Day of Yoga in Myanmar highlights its growing significance and the global recognition of its benefits.

Yoga is therefore gaining popularity in Myanmar and is viewed as a way to promote physical, mental and spiritual well-being. It is often practised in conjunction with meditation, reflecting the influence of Buddhism in the country. Yoga studios and retreats are becoming more common, offering a variety of classes and workshops for different levels of practitioners.

My personal experience in Myanmar so far is a blend of ancient history, vibrant culture, and natural beauty, but the best part about Myanmar is its beautiful people. The love and warmth which I receive from my Yoga students is overwhelming.

GNLM

On 20 March 2025, Penn Orthopaedics at the University of Pennsylvania in the United States hosted the annual San Baw, MD, GM ‘58 Honorary Lecture in Orthopaedic Innovation featuring Dr Arnold-Peter C Weiss from the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), who was the honorary speaker.

A brief bio-data of Dr San Baw and the youngest person (at the age of 13) to be inserted with an ivory hip prosthesis: Daw Than Htay

On 20 March 2025, Penn Orthopaedics at the University of Pennsylvania in the United States hosted the annual San Baw, MD, GM ‘58 Honorary Lecture in Orthopaedic Innovation featuring Dr Arnold-Peter C Weiss from the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), who was the honorary speaker.

A brief bio-data of Dr San Baw and the youngest person (at the age of 13) to be inserted with an ivory hip prosthesis: Daw Than Htay

Dr San Baw (29 June1922-7 December 1984) was my late father.

In January 1960, my late father first used an ivory prosthesis to replace the fractured thigh bone of an 83-year-old Burmese Buddhist nun, Daw Punya. He had to go to an ivory carver in the city of Mandalay to sculpt an ivory hip prosthesis. After his return from the University of Pennsylvania, doing his post-graduate studies for 3 1/2 years, my father was posted as Head of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at Mandalay General Hospital from November 1958 to June 1975. And he was posted as chief of orthopaedic surgery at Rangoon (now Yangon) General Hospital from June 1975 until his retirement in October 1980. From 1960 to 1980, Dr San Baw and his junior colleagues operated upon and inserted ivory hip prostheses to replace the fractured thigh bones of patients whose ages ranged from 13 to 87. Definitely one, if not two, persons who Dr San Baw inserted ivory hip prostheses are still alive as of mid-April 2025. On or about December 1969, a person from a village near Mandalay at the age of about thirteen was inserted with an ivory hip prostheses by my late father and his junior colleagues in an operation which lasted for about four hours (as told to me by the patient herself). The patient’s name is Daw Than Htay (born around November 1956). Up till about mid-2021, she lived in a village about a hundred and fifty miles from Mandalay. She currently lives in a monastery in Mandalay. Sometime in 2024, an X Ray was taken of her left hip (about 55 years after her insertion of the ivory prosthesis), and even though the prosthesis was broken, there has been a creeping substitution or ‘biological bonding’ between bone and ivory, the 2024 X-rays show.

Abstract of Presentation at British Orthopaedic Conference in 1969 and Master of Medical Science thesis at the University of Pennsylvania in 1957

My late father was invited by the British Orthopaedic Association to deliver his research on ivory hip prostheses at the annual conference of the British Orthopaedic Association (BOA) in London, which was held from September 23 to 27, 1969. But only an abstract of my father’s presentation was published in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British volume), Volume 59 B. When I wrote to the BOA sometime around 2019, they stated that they do not have the full paper any more with them. It is ironic that a paper that was presented to the BOA in 1969 is not on record with the BOA but a Master of Medical Science (Orthopaedics) thesis presented to the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the then Graduate School of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania by my late father in late 1957 is in the repository of the University of Pennsylvania library.

No killing of elephants in Burma when ivory prostheses were being used for the non-reunion of the femoral head

In the context of Burma from the 1960s to the early 1990s, ivory was a cheaper material to use as implants or prostheses to replace fractured thigh bones. Starting from 1959 in Mandalay, Dr San Baw studied the physical, mechanical, chemical and biological properties of ivory for about a year before he inserted it as a replacement on the 83-year-old Burmese Buddhist nun Daw Punya in January 1960. He consulted a physics professor and a zoology professor when investigating the physical, mechanical and biological properties of ivory. It must be emphasized that when my father was using ivory to replace hip fractures from the 1960s to early 1980s, there was no (no) killing of elephants. Only when elephants died say carrying logs after living their natural lives, was the ivory extracted from the elephants. Indeed, about ten years after Dr San Baw passed away in December 1984, his junior colleagues continued to use ivory prostheses as hip implants. One such patient, now deceased, Daw (Mrs, honorific) Than Than (May 1923-May 2023) (a different person from Daw Than Htay mentioned above) had a fall and fractured her left hip sometime after 1990. Professor U Meik, a junior colleague of Dr San Baw, an orthopaedic surgeon in Mandalay, used an ivory hip prosthesis in the early 1990s as a hip replacement for Daw Than Than. In October 2014, the elderly lady broke her right hip, and another orthopaedic surgeon replaced it with a metal hip prosthesis

Cover Story in Clinical Orthopaedics Journal of Dr San Baw’s work and Inaugural San Baw Lecture in Orthopaedic Innovation

In August 2017, Clinical Orthopaedics Journal published the case of the only person in the world then over the age of ninety years who had an ivory prosthesis in her left hip and metal prostheses in her right hip, with photos of X-rays. On the cover of the Journal, the photos of ivory hip prostheses that yours truly sent to the Journal were ‘touched up’ and displayed.

In December 2017, I contributed funds to the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania to establish an annual Lecture in perpetuity in my father’s name: ‘San Baw, MD. GM’58 Honorary Lecture in Orthopaedic Innovation’.

On 29 November 2018, Dr Bartek Szostakowski, a Polish orthopaedic surgeon at the Maria Sklodowska Curie Memorial Cancer Centre and Institute of Oncology in Warsaw, Poland, gave the inaugural ‘San Baw, Honorary Lecture in Orthopaedic Innovation’ titled ‘Dr San Baw, a forgotten innovator in orthopaedic biologic reconstruction’. I also gave a presentation, ‘Dr San Baw: A Son’s Tribute to an Ivory Prince’. From 2022 to 2025, there have been four San Baw Lectures in Orthopaedic innovation that were held at the University of Pennsylvania in honour of Dr San Baw. After the two inaugural Lectures by me and Dr Bartek, Dr L Scott Levin, Chair of Orthopaedic Surgery at Penn, stated that ‘San Baw was an innovative, compassionate physician who pioneered techniques in hip arthroplasty … We are delighted to perpetuate the legacy of this remarkable orthopaedic surgeon’.

Scant domestic and international recognition in relation to Dr San Baw’s contributions

Sir John Charnley (29 August 1911-5 August 1982), a British orthopaedic surgeon, was recognised as the founder of modern hip replacement (total hip arthroplasty) and, in layperson’s terms, one of the leading pioneers of metal hip prostheses. When he passed away in 1982, there was a short obituary of him in the New York Times. (26 August 1982, Section B, page 12). In 1990, British orthopaedic surgeon William Waugh (17 February 1922-21 May 1998) published a biography of Sir John, titled John Charnley [:] The Man and the Hip (Springer-Verlag).

The next year in 1983, another pioneer of vitallium hip prostheses, an American orthopaedic surgeon, Dr Frederick Thompson (1907-April 12,1983), passed away. The New York Times also published a longer obituary on its 15 April 1983 issue (Section D at page 18). But when Dr San Baw passed away just over 1 ½ years after Dr Frederick Thompson and just over 2 years after Sir John Charnley did, forget the New York Times, not even local Burmese and English language newspapers carried the news.

But I should say that about 10 of the newspapers in the United States did carry a news item under various headings, including ‘Ivory replaces metal in bone transplants’ written by journalist Albert E Kaff (1920-October 2011) in January and February 1970 issues. After my father passed away, I saw three handwritten letters addressed to my father, ‘Dr San Baw, Mandalay General Hospital, Mandalay, Burma’. The letters all came from the United States asking my father’s advice for their orthopaedic problems. One of the correspondents attached a cutting of a news item under the above title from the San Bernardino County Sun newspaper of 31 January 1970. Albert E Kaff was reporting on the ‘Lecture Dr San Baw at the British Orthopaedic Association in London in September 1969’, the UPI report by Albert E Kaff might have reached the Editors’ desk of the New York Times in early 1970, they might not have published it.

Ivory prostheses sample and prosthetic work being done ‘in Malaysia’: A correction

Still, smidgens (so to speak) of recognition somewhat belatedly came. There is a display (since when I do not know) of a sample of ivory prosthesis in the Museum of Surgery in Edinburgh, Scotland, Great Britain. I was not aware of the display at the museum until a former student wrote to me in 2017 about it. Ms Teo Ju-li, a Malaysian student, was then studying for her Master of Laws (LLM) at the University of Edinburgh, and she visited the Museum. She saw the ivory prosthesis on display and wrote to me about it. At my request, an official of the Museum sent me a photo of the ivory hip prosthesis on display at the Museum of Surgery. It wrongly and briefly stated that it was from ‘Malaysia’. I sent a few documents concerning my late father, and the museum personnel kindly changed it to QUOTE ‘Burma (1970). Dr San Baw first used an ivory prosthesis on a Burmese Buddhist nun in 1960. Over 300 prostheses were used in 20 years with 90 per cent success, where patients were able to walk, squat and play football.’ UNQUOTE

The ‘mistake’ of Malaysia for Burma/Myanmar is made not only by the Museum of Surgery in Edinburgh. In a 90-second brief introduction of my late father in the 5th San Baw Honorary Lecture in Orthopaedic Innovation on March 20, 2025 (as indicated above), the introducer correctly stated that Dr San Baw worked at MGH (Mandalay General Hospital) and RGH (Rangoon General Hospital). But in the video link provided to me, where the Lecture was recorded, it was stated that these were the two medical hospitals in ‘Malaysia’ (not Burma) or Myanmar. I should say, though, that in the pamphlet distributed before and during the Lecture, the information regarding my father and Burmese background is correctly stated.

A Malaysian patient and Australian colleagues of Dr San Baw

As it was, Dr San Baw has had some Malaysian and Australian connections as well. From January to June 1976, on a World Health Organization (WHO) Fellowship, he visited orthopaedic centres in Malaysia, Singapore, Australia and Hong Kong. He was in Malaysia in January 1976, visiting the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Malaya Hospital. The then Head of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Malaya (UM) Hospital, the late Professor Dr Subramaniam, personally told me in 1990 that Dr San Baw treated the then Malaysian kid who had extra shin bone (infantile pseudarthrosis of the tibia) with his own technique. Incidentally even though BOA only published a 311word abstract of my father’s presentation in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British volume) (JBJS) in 1970 it did publish in full Dr San Baw’s article ‘The Transarticular graft for infantile pseudarthrosis of the tibia: A New Technique’ in Volume 57 (1975) of the above journal. Again, it is ironic that 14 case studies over a period of eight years on infantile pseudarthrosis were published in full in JBJS in 1975, but 100-plus studies on the insertion of ivory prostheses over a period of nine years were published only in abstract form five years earlier in 1970. But as the late Dr Subramaniam told me, a non-Burmese Malaysian boy (as he then was) in 1976 was also the beneficiary of my father’s innovative technique and compassion.

During his 1976 visit, Dr San Baw spent about two to three months in Australia visiting orthopaedic centres in Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth. I am in contact with only one Australian orthopaedic surgeon whom my father met in Australia and who, between 1976 and 2018, has visited Burma/Myanmar about 16 times. He is Emeritus Clinical Professor in Orthopaedics, Dr Robert Bauze of the University of Adelaide. It was in Australia, I understand, that Dr San Baw was called ‘ivory prince’.

Expression of thanks to Australian Colleagues, to Dr Bartek and Dr San Baw’s junior colleagues

I am grateful to Professor Bauze for his many visits to Burma/Myanmar and his assistance in facilitating Burmese orthopaedists and other medical doctors to get their training in Australia and for the Australian health aid projects in Myanmar. I am also grateful to Dr Bartek, as stated above, for re-introducing, reviving the ‘forgotten innovator’ Dr San Baw’s contributions to orthopaedics. Also, my thanks to former junior colleagues of Dr San Baw, Dr (Bobby) Sein Lwin (Florida), Professor Dr Kyaw Myint Naing (Yangon) My father Dr San Baw had in a small corner of the world assiduously and devotedly worked for the welfare of several hundred patients and had trained Burmese orthopaedic surgeons with dedication and compassion.

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

On 20 March 2025, Penn Orthopaedics at the University of Pennsylvania in the United States hosted the annual San Baw, MD, GM ‘58 Honorary Lecture in Orthopaedic Innovation featuring Dr Arnold-Peter C Weiss from the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), who was the honorary speaker.

A brief bio-data of Dr San Baw and the youngest person (at the age of 13) to be inserted with an ivory hip prosthesis: Daw Than Htay

Dr San Baw (29 June1922-7 December 1984) was my late father.

In January 1960, my late father first used an ivory prosthesis to replace the fractured thigh bone of an 83-year-old Burmese Buddhist nun, Daw Punya. He had to go to an ivory carver in the city of Mandalay to sculpt an ivory hip prosthesis. After his return from the University of Pennsylvania, doing his post-graduate studies for 3 1/2 years, my father was posted as Head of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at Mandalay General Hospital from November 1958 to June 1975. And he was posted as chief of orthopaedic surgery at Rangoon (now Yangon) General Hospital from June 1975 until his retirement in October 1980. From 1960 to 1980, Dr San Baw and his junior colleagues operated upon and inserted ivory hip prostheses to replace the fractured thigh bones of patients whose ages ranged from 13 to 87. Definitely one, if not two, persons who Dr San Baw inserted ivory hip prostheses are still alive as of mid-April 2025. On or about December 1969, a person from a village near Mandalay at the age of about thirteen was inserted with an ivory hip prostheses by my late father and his junior colleagues in an operation which lasted for about four hours (as told to me by the patient herself). The patient’s name is Daw Than Htay (born around November 1956). Up till about mid-2021, she lived in a village about a hundred and fifty miles from Mandalay. She currently lives in a monastery in Mandalay. Sometime in 2024, an X Ray was taken of her left hip (about 55 years after her insertion of the ivory prosthesis), and even though the prosthesis was broken, there has been a creeping substitution or ‘biological bonding’ between bone and ivory, the 2024 X-rays show.

Abstract of Presentation at British Orthopaedic Conference in 1969 and Master of Medical Science thesis at the University of Pennsylvania in 1957

My late father was invited by the British Orthopaedic Association to deliver his research on ivory hip prostheses at the annual conference of the British Orthopaedic Association (BOA) in London, which was held from September 23 to 27, 1969. But only an abstract of my father’s presentation was published in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British volume), Volume 59 B. When I wrote to the BOA sometime around 2019, they stated that they do not have the full paper any more with them. It is ironic that a paper that was presented to the BOA in 1969 is not on record with the BOA but a Master of Medical Science (Orthopaedics) thesis presented to the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the then Graduate School of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania by my late father in late 1957 is in the repository of the University of Pennsylvania library.

No killing of elephants in Burma when ivory prostheses were being used for the non-reunion of the femoral head

In the context of Burma from the 1960s to the early 1990s, ivory was a cheaper material to use as implants or prostheses to replace fractured thigh bones. Starting from 1959 in Mandalay, Dr San Baw studied the physical, mechanical, chemical and biological properties of ivory for about a year before he inserted it as a replacement on the 83-year-old Burmese Buddhist nun Daw Punya in January 1960. He consulted a physics professor and a zoology professor when investigating the physical, mechanical and biological properties of ivory. It must be emphasized that when my father was using ivory to replace hip fractures from the 1960s to early 1980s, there was no (no) killing of elephants. Only when elephants died say carrying logs after living their natural lives, was the ivory extracted from the elephants. Indeed, about ten years after Dr San Baw passed away in December 1984, his junior colleagues continued to use ivory prostheses as hip implants. One such patient, now deceased, Daw (Mrs, honorific) Than Than (May 1923-May 2023) (a different person from Daw Than Htay mentioned above) had a fall and fractured her left hip sometime after 1990. Professor U Meik, a junior colleague of Dr San Baw, an orthopaedic surgeon in Mandalay, used an ivory hip prosthesis in the early 1990s as a hip replacement for Daw Than Than. In October 2014, the elderly lady broke her right hip, and another orthopaedic surgeon replaced it with a metal hip prosthesis

Cover Story in Clinical Orthopaedics Journal of Dr San Baw’s work and Inaugural San Baw Lecture in Orthopaedic Innovation

In August 2017, Clinical Orthopaedics Journal published the case of the only person in the world then over the age of ninety years who had an ivory prosthesis in her left hip and metal prostheses in her right hip, with photos of X-rays. On the cover of the Journal, the photos of ivory hip prostheses that yours truly sent to the Journal were ‘touched up’ and displayed.

In December 2017, I contributed funds to the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania to establish an annual Lecture in perpetuity in my father’s name: ‘San Baw, MD. GM’58 Honorary Lecture in Orthopaedic Innovation’.

On 29 November 2018, Dr Bartek Szostakowski, a Polish orthopaedic surgeon at the Maria Sklodowska Curie Memorial Cancer Centre and Institute of Oncology in Warsaw, Poland, gave the inaugural ‘San Baw, Honorary Lecture in Orthopaedic Innovation’ titled ‘Dr San Baw, a forgotten innovator in orthopaedic biologic reconstruction’. I also gave a presentation, ‘Dr San Baw: A Son’s Tribute to an Ivory Prince’. From 2022 to 2025, there have been four San Baw Lectures in Orthopaedic innovation that were held at the University of Pennsylvania in honour of Dr San Baw. After the two inaugural Lectures by me and Dr Bartek, Dr L Scott Levin, Chair of Orthopaedic Surgery at Penn, stated that ‘San Baw was an innovative, compassionate physician who pioneered techniques in hip arthroplasty … We are delighted to perpetuate the legacy of this remarkable orthopaedic surgeon’.

Scant domestic and international recognition in relation to Dr San Baw’s contributions

Sir John Charnley (29 August 1911-5 August 1982), a British orthopaedic surgeon, was recognised as the founder of modern hip replacement (total hip arthroplasty) and, in layperson’s terms, one of the leading pioneers of metal hip prostheses. When he passed away in 1982, there was a short obituary of him in the New York Times. (26 August 1982, Section B, page 12). In 1990, British orthopaedic surgeon William Waugh (17 February 1922-21 May 1998) published a biography of Sir John, titled John Charnley [:] The Man and the Hip (Springer-Verlag).

The next year in 1983, another pioneer of vitallium hip prostheses, an American orthopaedic surgeon, Dr Frederick Thompson (1907-April 12,1983), passed away. The New York Times also published a longer obituary on its 15 April 1983 issue (Section D at page 18). But when Dr San Baw passed away just over 1 ½ years after Dr Frederick Thompson and just over 2 years after Sir John Charnley did, forget the New York Times, not even local Burmese and English language newspapers carried the news.

But I should say that about 10 of the newspapers in the United States did carry a news item under various headings, including ‘Ivory replaces metal in bone transplants’ written by journalist Albert E Kaff (1920-October 2011) in January and February 1970 issues. After my father passed away, I saw three handwritten letters addressed to my father, ‘Dr San Baw, Mandalay General Hospital, Mandalay, Burma’. The letters all came from the United States asking my father’s advice for their orthopaedic problems. One of the correspondents attached a cutting of a news item under the above title from the San Bernardino County Sun newspaper of 31 January 1970. Albert E Kaff was reporting on the ‘Lecture Dr San Baw at the British Orthopaedic Association in London in September 1969’, the UPI report by Albert E Kaff might have reached the Editors’ desk of the New York Times in early 1970, they might not have published it.

Ivory prostheses sample and prosthetic work being done ‘in Malaysia’: A correction

Still, smidgens (so to speak) of recognition somewhat belatedly came. There is a display (since when I do not know) of a sample of ivory prosthesis in the Museum of Surgery in Edinburgh, Scotland, Great Britain. I was not aware of the display at the museum until a former student wrote to me in 2017 about it. Ms Teo Ju-li, a Malaysian student, was then studying for her Master of Laws (LLM) at the University of Edinburgh, and she visited the Museum. She saw the ivory prosthesis on display and wrote to me about it. At my request, an official of the Museum sent me a photo of the ivory hip prosthesis on display at the Museum of Surgery. It wrongly and briefly stated that it was from ‘Malaysia’. I sent a few documents concerning my late father, and the museum personnel kindly changed it to QUOTE ‘Burma (1970). Dr San Baw first used an ivory prosthesis on a Burmese Buddhist nun in 1960. Over 300 prostheses were used in 20 years with 90 per cent success, where patients were able to walk, squat and play football.’ UNQUOTE

The ‘mistake’ of Malaysia for Burma/Myanmar is made not only by the Museum of Surgery in Edinburgh. In a 90-second brief introduction of my late father in the 5th San Baw Honorary Lecture in Orthopaedic Innovation on March 20, 2025 (as indicated above), the introducer correctly stated that Dr San Baw worked at MGH (Mandalay General Hospital) and RGH (Rangoon General Hospital). But in the video link provided to me, where the Lecture was recorded, it was stated that these were the two medical hospitals in ‘Malaysia’ (not Burma) or Myanmar. I should say, though, that in the pamphlet distributed before and during the Lecture, the information regarding my father and Burmese background is correctly stated.

A Malaysian patient and Australian colleagues of Dr San Baw

As it was, Dr San Baw has had some Malaysian and Australian connections as well. From January to June 1976, on a World Health Organization (WHO) Fellowship, he visited orthopaedic centres in Malaysia, Singapore, Australia and Hong Kong. He was in Malaysia in January 1976, visiting the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Malaya Hospital. The then Head of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Malaya (UM) Hospital, the late Professor Dr Subramaniam, personally told me in 1990 that Dr San Baw treated the then Malaysian kid who had extra shin bone (infantile pseudarthrosis of the tibia) with his own technique. Incidentally even though BOA only published a 311word abstract of my father’s presentation in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British volume) (JBJS) in 1970 it did publish in full Dr San Baw’s article ‘The Transarticular graft for infantile pseudarthrosis of the tibia: A New Technique’ in Volume 57 (1975) of the above journal. Again, it is ironic that 14 case studies over a period of eight years on infantile pseudarthrosis were published in full in JBJS in 1975, but 100-plus studies on the insertion of ivory prostheses over a period of nine years were published only in abstract form five years earlier in 1970. But as the late Dr Subramaniam told me, a non-Burmese Malaysian boy (as he then was) in 1976 was also the beneficiary of my father’s innovative technique and compassion.

During his 1976 visit, Dr San Baw spent about two to three months in Australia visiting orthopaedic centres in Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth. I am in contact with only one Australian orthopaedic surgeon whom my father met in Australia and who, between 1976 and 2018, has visited Burma/Myanmar about 16 times. He is Emeritus Clinical Professor in Orthopaedics, Dr Robert Bauze of the University of Adelaide. It was in Australia, I understand, that Dr San Baw was called ‘ivory prince’.

Expression of thanks to Australian Colleagues, to Dr Bartek and Dr San Baw’s junior colleagues

I am grateful to Professor Bauze for his many visits to Burma/Myanmar and his assistance in facilitating Burmese orthopaedists and other medical doctors to get their training in Australia and for the Australian health aid projects in Myanmar. I am also grateful to Dr Bartek, as stated above, for re-introducing, reviving the ‘forgotten innovator’ Dr San Baw’s contributions to orthopaedics. Also, my thanks to former junior colleagues of Dr San Baw, Dr (Bobby) Sein Lwin (Florida), Professor Dr Kyaw Myint Naing (Yangon) My father Dr San Baw had in a small corner of the world assiduously and devotedly worked for the welfare of several hundred patients and had trained Burmese orthopaedic surgeons with dedication and compassion.

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

Hitting 10,000 steps a day is a goal for millions of us. But the number of minutes we walk for may be a more important target to focus on.

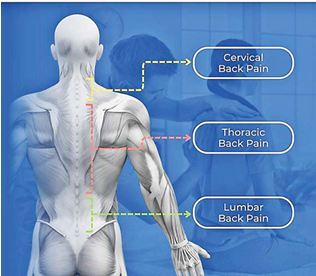

Scientists believe being on your feet for over an hour-and-a-half every day could slash the risk of chronic lower back pain.

Norwegian and Danish researchers found people who walk for over 100 minutes a day cut this risk by almost a quarter compared to those who clocked 78 minutes per day or less.

Hitting 10,000 steps a day is a goal for millions of us. But the number of minutes we walk for may be a more important target to focus on.

Scientists believe being on your feet for over an hour-and-a-half every day could slash the risk of chronic lower back pain.

Norwegian and Danish researchers found people who walk for over 100 minutes a day cut this risk by almost a quarter compared to those who clocked 78 minutes per day or less.

They also discovered faster walkers were less likely to have chronic back pain—but the effect was less pronounced than walking for longer.

Experts, who labelled the findings important, urged policy makers to push walking as a 'public health strategy' to reduce the risk of the agonising condition.

In many cases, lower back pain starts suddenly and improves within a few days or weeks.

But if it sticks around for more than three months, it’s classed as chronic, according to the NHS. In some cases, it can be considered a disability.

In the study, 11,194 Norwegians, with an average age of 55, were quizzed on their health and how much exercise they did per week.

Almost a sixth (14.8 per cent) reported suffering from lower back pain, answering 'yes' to the following questions, 'During the last year, have you had pain and/or stiffness in your muscles or joints that lasted for at least three consecutive months? and 'Where have you had this pain or stiffness?'

Participants were considered to have the condition if they answered yes to the first question and reported pain in the lower back to the second.

Both men and women were involved in the study, and 100 minutes was found to be the optimum length of time for both sexes, and all ages.

Writing in the journal JAMA Network Open, the researchers concluded: ‘Compared with walking less than 78 minutes per day, those who walked more than 100 minutes per day had a 23 per cent reduced risk of chronic lower back pain.

'The reduction in risk of chronic lower back pain leveled off beyond a walking volume of about 100 minutes per day.

‘Our findings suggest that daily walking volume is more important than mean walking intensity in reducing the risk of chronic lower back pain.

‘These findings suggest that policies and public health strategies promoting walking could help to reduce the occurrence of chronic lower back pain.’

The researchers also noted that their results are ‘likely generalisable beyond the Norwegian adult population, as physical inactivity prevalence in Norway is comparable to that observed in other high-income countries’.

They did note some limitations of the study, including that participants with higher walking volume tended to exercise more often and reported higher physical work demands, which might give them a physical advantage over other members of the group.

In the UK, musculoskeletal conditions (MSK)—including back pain—are the second biggest reason for people being ‘economically inactive’—where someone is out of work and not looking for work.

Figures released by the Government in December 2024 revealed that MSK conditions affect approximately 646,000 Britons, 1-in-4 of the 2.8m who are claiming long-term sickness benefits.

MSK comes second only to mental health issues for reasons why people are unable to work.

It was estimated that 23.4 million working days in the UK were lost due to MSK conditions in 2022.

NHS waiting lists for MSK community services are the highest of all community waits in England, with 348,799 people in September 2024 waiting to see a specialist.

As part of their Get Britain Working White Paper, the Government pledged a £3.5million package to 17 Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) across England to improve local MSK services.

Mail Online

Hitting 10,000 steps a day is a goal for millions of us. But the number of minutes we walk for may be a more important target to focus on.

Scientists believe being on your feet for over an hour-and-a-half every day could slash the risk of chronic lower back pain.

Norwegian and Danish researchers found people who walk for over 100 minutes a day cut this risk by almost a quarter compared to those who clocked 78 minutes per day or less.

They also discovered faster walkers were less likely to have chronic back pain—but the effect was less pronounced than walking for longer.

Experts, who labelled the findings important, urged policy makers to push walking as a 'public health strategy' to reduce the risk of the agonising condition.

In many cases, lower back pain starts suddenly and improves within a few days or weeks.

But if it sticks around for more than three months, it’s classed as chronic, according to the NHS. In some cases, it can be considered a disability.

In the study, 11,194 Norwegians, with an average age of 55, were quizzed on their health and how much exercise they did per week.

Almost a sixth (14.8 per cent) reported suffering from lower back pain, answering 'yes' to the following questions, 'During the last year, have you had pain and/or stiffness in your muscles or joints that lasted for at least three consecutive months? and 'Where have you had this pain or stiffness?'

Participants were considered to have the condition if they answered yes to the first question and reported pain in the lower back to the second.

Both men and women were involved in the study, and 100 minutes was found to be the optimum length of time for both sexes, and all ages.

Writing in the journal JAMA Network Open, the researchers concluded: ‘Compared with walking less than 78 minutes per day, those who walked more than 100 minutes per day had a 23 per cent reduced risk of chronic lower back pain.

'The reduction in risk of chronic lower back pain leveled off beyond a walking volume of about 100 minutes per day.

‘Our findings suggest that daily walking volume is more important than mean walking intensity in reducing the risk of chronic lower back pain.

‘These findings suggest that policies and public health strategies promoting walking could help to reduce the occurrence of chronic lower back pain.’

The researchers also noted that their results are ‘likely generalisable beyond the Norwegian adult population, as physical inactivity prevalence in Norway is comparable to that observed in other high-income countries’.

They did note some limitations of the study, including that participants with higher walking volume tended to exercise more often and reported higher physical work demands, which might give them a physical advantage over other members of the group.

In the UK, musculoskeletal conditions (MSK)—including back pain—are the second biggest reason for people being ‘economically inactive’—where someone is out of work and not looking for work.

Figures released by the Government in December 2024 revealed that MSK conditions affect approximately 646,000 Britons, 1-in-4 of the 2.8m who are claiming long-term sickness benefits.

MSK comes second only to mental health issues for reasons why people are unable to work.

It was estimated that 23.4 million working days in the UK were lost due to MSK conditions in 2022.

NHS waiting lists for MSK community services are the highest of all community waits in England, with 348,799 people in September 2024 waiting to see a specialist.

As part of their Get Britain Working White Paper, the Government pledged a £3.5million package to 17 Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) across England to improve local MSK services.

Mail Online

Why is cycling one of the best Exercises for every lifestyle? In a world where people are becoming more aware of the importance of maintaining physical and mental health, finding the right form of exercise is key. For many, the solution might be simpler – and more enjoyable – than they think: cycling.

Why is cycling one of the best Exercises for every lifestyle? In a world where people are becoming more aware of the importance of maintaining physical and mental health, finding the right form of exercise is key. For many, the solution might be simpler – and more enjoyable – than they think: cycling.

Whether you’re cruising down a quiet neighbourhood road, commuting to work, joining a spin class at the gym, or pedalling at home on a stationary bike, cycling is a powerful and flexible form of exercise. Not only does it improve physical health, but it also supports mental well-being, offers practical lifestyle benefits, and even helps protect the environment.

Let’s explore why cycling continues to gain popularity around the world and why it might just be the perfect activity to incorporate into your life – no matter your age, schedule, or fitness level.

An Exercise That Moves Your Heart (Literally)

One of the most celebrated benefits of cycling is how it supports heart health. As an aerobic exercise, cycling increases your heart rate and improves blood circulation throughout your body. Studies have shown that regular cyclists tend to have lower blood pressure and resting heart rates compared to inactive people.

Research has also revealed that people who cycle regularly are at a significantly reduced risk of developing coronary heart disease or suffering a heart attack. That’s because cycling helps keep your heart strong and arteries clear, reducing strain on the cardiovascular system. Just a few sessions a week, even at a moderate pace, can dramatically improve your cardiovascular fitness.

Gentle on the Joints, Powerful in Impact

Unlike activities such as running, which place repeated stress on your joints, cycling is a low-impact activity. This makes it especially appealing for people with joint issues, older adults, or those recovering from injuries.

Cycling is commonly used in physical therapy and rehabilitation programs. It promotes mobility, increases range of motion, and improves strength – all without putting your knees, hips, and ankles under heavy pressure.

A 2024 study found that people with osteoarthritis who incorporated cycling into their weekly routine experienced less knee pain than non-cyclists. This shows how effective and gentle cycling can be for long-term joint health.

Maintaining a Healthy Weight Made Easier

Weight management is a challenge for many, especially with busy schedules and sedentary lifestyles. Fortunately, cycling provides a fun, convenient way to help keep your weight in check. Regular cyclists often maintain a healthier body composition, which refers to the balance between fat, muscle, bone, and water in the body. Cycling burns calories, builds muscle, and boosts metabolism – all of which are essential for weight control.

The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week. Cycling is a great way to meet that recommendation. Whether you bike for 30 minutes five days a week or do three 50-minute sessions, you’ll be helping your body stay fit and active.

Want to lose weight? Increase your intensity by riding uphill, speeding up your pace, or extending your cycling sessions. These adjustments will boost your calorie burn and help you reach your goals faster.

Boost Your Mood, Beat the Blues

Exercise doesn’t just make your body stronger – it lifts your spirits, too. Physical activities like cycling release endorphins, the “feel-good” chemicals that improve mood and reduce stress.

People who cycle regularly often report better sleep, lower levels of anxiety and depression, and an overall improved sense of well-being. Whether it’s the rhythmic motion of pedalling or the calming effect of fresh air and sunshine, biking can be a great mental escape.

Cycling outdoors adds another layer of benefits. Being in nature, enjoying the scenery, and soaking in sunlight can help fight seasonal mood disorders and brighten your day, even after just a short ride.

Preventing Type 2 Diabetes Through Pedal Power

Cycling can play a key role in preventing chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes. This condition is often linked to poor lifestyle habits, including a lack of physical activity and unhealthy weight gain. By promoting weight control and improving insulin sensitivity, cycling helps your body better regulate blood sugar levels. Studies have shown that people who bike to work or use cycling as a form of exercise have a significantly lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Making cycling a part of your daily or weekly routine could be one of the simplest ways to protect your long-term health.

More Than Exercise: A Lifestyle Choice with Real-World Benefits

Cycling isn’t just a workout – it’s also a practical and sustainable way to live. When used as a mode of transportation, biking helps you save money on gas, parking, and public transport. It also reduces wear and tear on your vehicle and minimizes your carbon footprint. Each time you choose a bike over a car, you’re reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This is a powerful way to combat climate change and improve air quality in your community. Cleaner air leads to better public health and fewer respiratory issues, especially for children and the elderly.

Cycling can also strengthen family bonds. Parents can encourage children to be more active by going on bike rides together. It’s a fun and healthy way to spend time as a family while developing good habits.

Stronger Muscles, Healthier Ageing

Cycling doesn’t just benefit your heart and lungs – it also strengthens muscles throughout your body, particularly in your legs, hips, and core. Each pedal stroke works your quadriceps, hamstrings, calves, and glutes. These muscle groups are essential for balance, walking, climbing stairs, and other daily activities.

As we age, maintaining muscle mass becomes increasingly important. Loss of muscle can lead to falls, injuries, and reduced independence. Cycling provides a low-impact, effective way to slow muscle loss and preserve strength, especially for older adults.

Indoor versus Outdoor: Which Ride Is Right for You?

One of the great things about cycling is that it can be done indoors or outdoors, each with its advantages.

Outdoor cycling is perfect for exploring new places, commuting, or getting on a longer endurance ride. It’s also a great social activity, whether you join a group ride or take a leisurely cruise with friends.

Indoor cycling, on the other hand, offers predictability and control. Whether you’re in a spin class or using a stationary bike at home, indoor cycling allows you to adjust intensity easily and stick to a consistent workout schedule, rain or shine.

For those with limited time or living in urban areas with traffic and safety concerns, indoor cycling may be a better option. Plus, many modern stationary bikes offer built-in workout programs, virtual classes, and tracking features to help keep you motivated.

Who Should Be Cautious About Cycling?

While cycling is safe for most people, there are a few exceptions. Individuals prone to falls or those with severe balance problems should avoid traditional outdoor biking. For these individuals, recumbent bikes are a great alternative. These bikes have a reclined seat and are lower to the ground, providing better stability and comfort. However, they can be more expensive and take up more space.

If you’re unsure whether cycling is right for you, talk to your healthcare provider, especially if you have chronic health conditions or are recovering from surgery.

How to Start and Stick With Cycling

Getting started is easier than you might think. All you need is a bike and a little motivation.

Start small: Begin with 10–15 minutes a day and gradually build up to longer rides.

Be consistent: Aim for 150 minutes per week. That’s just 30 minutes a day for five days.

Choose your style: Try different types of cycling – commuting, spin class, indoor biking, or scenic weekend rides.

Stay safe: Always wear a helmet, follow traffic rules, and use lights or reflectors if cycling outdoors at night.

If you’re cycling indoors, experiment with different virtual classes or programs to find what keeps you engaged. From high-energy spin sessions to scenic virtual rides, there’s something for everyone.

Final Thoughts: Just Keep Pedalling

Cycling is one of the most adaptable and rewarding exercises you can choose. It offers a long list of physical, mental, and lifestyle benefits – from reducing your risk of disease to saving money and improving the planet.

Whether you’re an athlete looking for a new challenge, a busy professional needing a flexible workout, or a senior aiming to stay active and mobile, cycling has something to offer you. So, grab a helmet, hop on a bike, and start pedalling your way to better health. The journey might just be your best ride yet.

Source: The Global New Light of Myanmar

Why is cycling one of the best Exercises for every lifestyle? In a world where people are becoming more aware of the importance of maintaining physical and mental health, finding the right form of exercise is key. For many, the solution might be simpler – and more enjoyable – than they think: cycling.

Whether you’re cruising down a quiet neighbourhood road, commuting to work, joining a spin class at the gym, or pedalling at home on a stationary bike, cycling is a powerful and flexible form of exercise. Not only does it improve physical health, but it also supports mental well-being, offers practical lifestyle benefits, and even helps protect the environment.

Let’s explore why cycling continues to gain popularity around the world and why it might just be the perfect activity to incorporate into your life – no matter your age, schedule, or fitness level.

An Exercise That Moves Your Heart (Literally)

One of the most celebrated benefits of cycling is how it supports heart health. As an aerobic exercise, cycling increases your heart rate and improves blood circulation throughout your body. Studies have shown that regular cyclists tend to have lower blood pressure and resting heart rates compared to inactive people.

Research has also revealed that people who cycle regularly are at a significantly reduced risk of developing coronary heart disease or suffering a heart attack. That’s because cycling helps keep your heart strong and arteries clear, reducing strain on the cardiovascular system. Just a few sessions a week, even at a moderate pace, can dramatically improve your cardiovascular fitness.

Gentle on the Joints, Powerful in Impact

Unlike activities such as running, which place repeated stress on your joints, cycling is a low-impact activity. This makes it especially appealing for people with joint issues, older adults, or those recovering from injuries.

Cycling is commonly used in physical therapy and rehabilitation programs. It promotes mobility, increases range of motion, and improves strength – all without putting your knees, hips, and ankles under heavy pressure.

A 2024 study found that people with osteoarthritis who incorporated cycling into their weekly routine experienced less knee pain than non-cyclists. This shows how effective and gentle cycling can be for long-term joint health.

Maintaining a Healthy Weight Made Easier

Weight management is a challenge for many, especially with busy schedules and sedentary lifestyles. Fortunately, cycling provides a fun, convenient way to help keep your weight in check. Regular cyclists often maintain a healthier body composition, which refers to the balance between fat, muscle, bone, and water in the body. Cycling burns calories, builds muscle, and boosts metabolism – all of which are essential for weight control.

The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each week. Cycling is a great way to meet that recommendation. Whether you bike for 30 minutes five days a week or do three 50-minute sessions, you’ll be helping your body stay fit and active.

Want to lose weight? Increase your intensity by riding uphill, speeding up your pace, or extending your cycling sessions. These adjustments will boost your calorie burn and help you reach your goals faster.

Boost Your Mood, Beat the Blues

Exercise doesn’t just make your body stronger – it lifts your spirits, too. Physical activities like cycling release endorphins, the “feel-good” chemicals that improve mood and reduce stress.

People who cycle regularly often report better sleep, lower levels of anxiety and depression, and an overall improved sense of well-being. Whether it’s the rhythmic motion of pedalling or the calming effect of fresh air and sunshine, biking can be a great mental escape.