Yunnan Province, the closest Chinese territory to Myanmar geographically and ethnically, is rich in cultural heritage with natural resources. Stretching approximately 2,000 kilometres in borderline, Myanmar and China’s Yunnan Province have been standing together and sharing common values and cultures through all ups and downs, tied to history.

Eight-day visit that shaped regional integrity

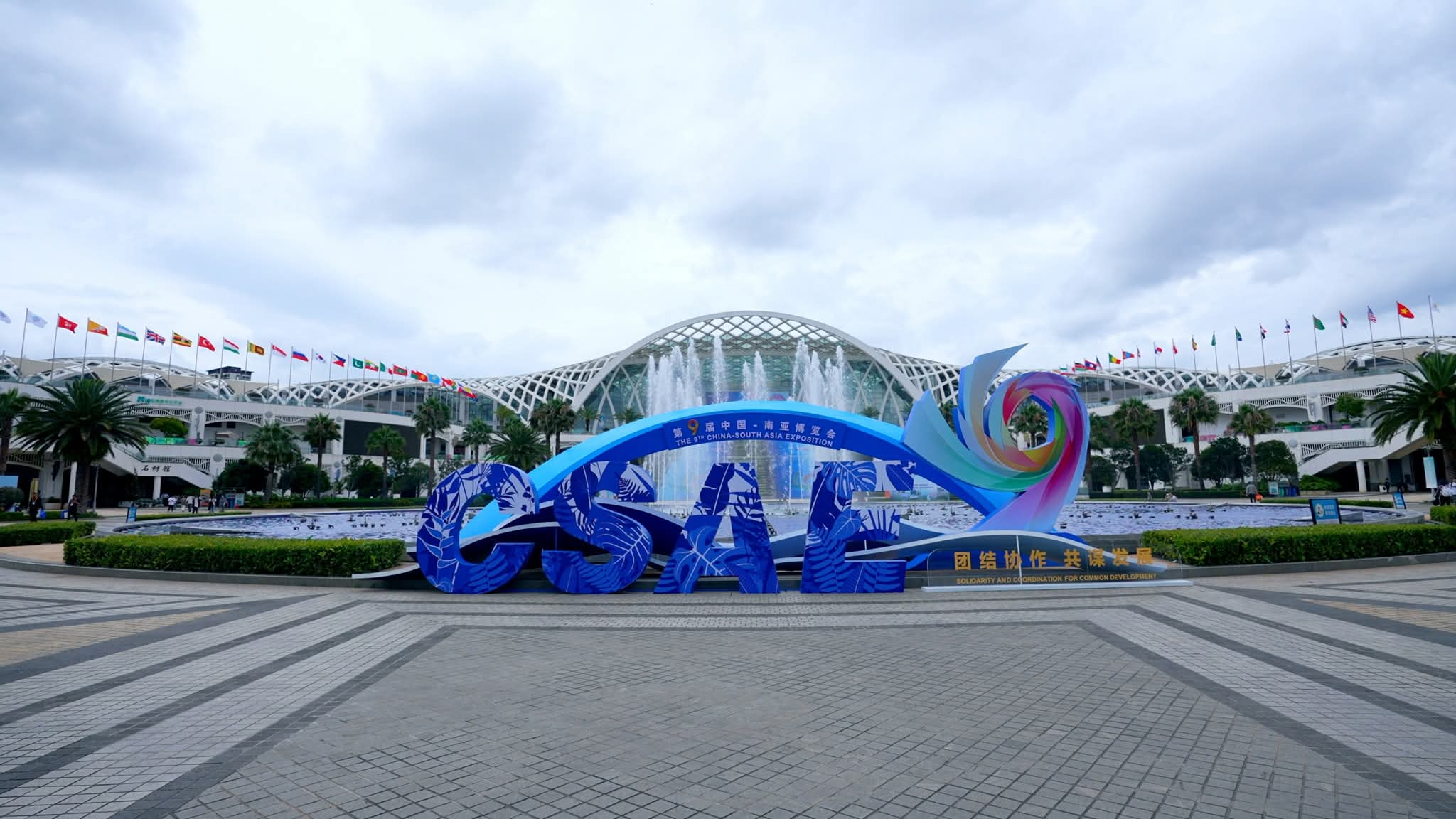

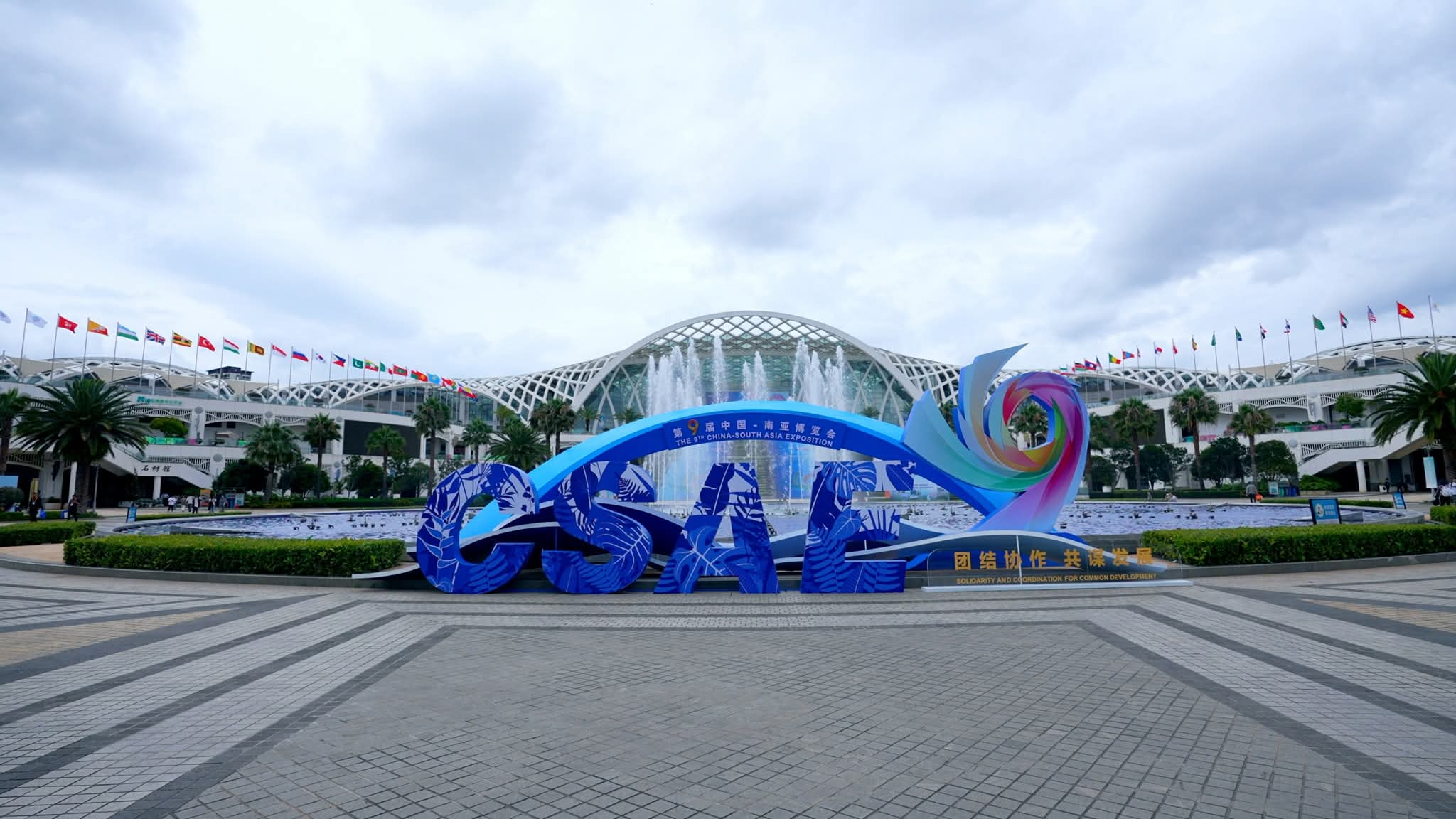

China hosted the 9th China-South Asia Exposition and the 29th China Kunming Import and Export Fair in Kunming, Yunnan Province, from 19 to 24 June. As a sideline event, Yunnan International Television Station organized the 4th Generation Z Lancang-Mekong Audio Visual Week 2025 from 20 to 25 June, which invited young diplomats from China’s neighbouring countries, aiming to strengthen regional integrity by reciprocal learning.

The eight-day programme brought together a total of 15 young diplomats from Mekong Region countries, as well as from maritime Southeast Asian nations like Malaysia and Indonesia, and South Asian countries such as Pakistan and Nepal, to participate in the project of creation camp project, aiming to expand cultural integrity among Asian civilizations. I was one of the participants to join it as a Myanmar media representative.

From my perspective, the whole program was designed to share knowledge of or exchange traditions, cultures and histories that have been upheld by Yunnan people up to these days since prehistoric time with Yunnan’s neighbouring Asian friends. Hence, it was fostering the comprehensive principles of the Chinese proposed Global Civilization Initiatives (GCI).

Essential means of the GCI can be interpreted as upholding humanity, respecting diversity of civilizations and inheritances, which in turn, promotes robust international people-to-people exchange. Understanding the versatile attitudes of different communities encourages harmonious cooperation while seeking a peaceful global order. Rejecting coercively exporting the phenomenon of ‘globalization’ with main adverse products: ‘Clash of Civilizations’ or ‘Cultural Shock’, the GCI emphasizes mutually exchanging social norms and common values under mutual learning. In these ways, the GCI aims to shape a global, peaceful environment with mutual respect.

Bound by nature to be the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation

Sightseeing picturesque natural landscapes and learning about the cultural diversity in Yunnan during the trip gave me of Asian countries, especially southern China, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam, sharing the same origins of continental resources with mountains, hills and rivers. Consequently, common cultural habits, ancestral rituals and social norms are being shared particularly within their closely related ethnical tribes of mainland Southeast Asia.

These shared cultural and geographical heritages reflect core values of the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation and the unity of the region.

Learning hotspots in the 4th Generation Z Lancang-Mekong Audio Visual Week 2025 were Chinese tea culture and tea history, and Yunnan’s Dai ethnic heritage, specifically in Pu’er and Xishuangbanna cities. In addition to them, the young Asian diplomats also partially studied the culturally related economic development of the province, and the fruitful hub in trade and transport of the China-Laos Railway.

Myanmar-Yunnan’s shared history from the Tea Horse Road to the CMEC

Pu’er City, the hidden paradise in Yunnan Province and is renowned as China’s tea capital, and has extensive tea plantations in both traditional and modern technologies. It could be learned that the city contributes a significant effort in China’s securing UNESCO heritage recognition of tea by advancing in research and development.

In 2022, UNESCO inscribed Chinese tea, its associated cultural practices like traditional tea processing techniques, China’s historical significance of tea, and its social importance in the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. China’s achievement of the intangible cultural heritage of tea at UNESCO is an earnest worthy.

Pu’er played a key role in tea trading back in many centuries ago as part of the ancient Chinese Silk Road to the west. To my knowledge, Myanmar was observed as one of Pu’er’s destinations in the Ancient Tea Horse Road, which started in the Tang Dynasty; then, flourished in the Ming Dynasty and Qing Dynasty.

Not only in the ancient Chinese Silk Road, Myanmar and China’s Yunnan Province also play key roles as the ‘China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC)’ in part of the modern-day Belt and Road Initiative. The project includes high-speed railways and highways by connecting Myanmar’s Kyaukphyu in Rakhine State through Mandalay, Lashio and Muse to Kunming in Yunnan. Extending to Yangon, the strategically proposed project is envisioned to promote regional economic integration and development. By these means, the regional GDP Index is expected to experience a big jump.

Pu’er’s educational support for Myanmar

Bound by history, China’s Yunnan Province and Myanmar have shared mutual coexistence in successive eras. Education is another key sector that fosters strong ties between the two countries.

I had the opportunity to visit Pu’er University during the programme, where approximately 20 Myanmar students are studying different subjects with Chinese scholarships.

“Every year, we have several Myanmar students. They are very good at Chinese and hardworking in their studies. All Myanmar students in Pu’er University are studying with different ranks of scholarships. Computer Science, Chinese Education, Mathematics and Management are the most favourite majors chosen by the Myanmar students,” said Director of the Office of International Cooperation and Exchange at Pu’er University, Mr Bai Leigang, adding that Pu’er University has a strong tie with Myanmar’s University of Yangon and the Yangon University of Foreign Languages. Both sides engage in annual student exchange programs and hold online meetings to strengthen their academic cooperation.

At present, China offers a range of government scholarships for Myanmar students, including the Chinese Government Scholarship (CSC), ASEAN-China Young Leaders Scholarship, Confucius Institute Scholarship/ Chinese Language Study Scholarships, Yunnan Provincial Government Scholarships, University-Specific Scholarships, and Silk Road Scholarship Program.

Furthermore, during the official visit of Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, Prime Minister and State Administration Council Chairman of Myanmar, to China last year in November, China pledged to provide more scholarship programs for Myanmar students shortly.

Myanmar, Yunnan stand together through all ups and downs

Last but not least, in the recent earthquake which hit Myanmar on 28 March 2025, China was the country that arrived in Myanmar the very first among international rescue operations. Sharing the borderline, the first Chinese rescue team with 32 members with rescue equipment from Yunnan Province arrived in Myanmar within 17 hours after the quake. It evidenced the strong solidarity existing between Myanmar and China, sharing weal and woe, particularly in the hardship times.

GNLM

Yunnan Province, the closest Chinese territory to Myanmar geographically and ethnically, is rich in cultural heritage with natural resources. Stretching approximately 2,000 kilometres in borderline, Myanmar and China’s Yunnan Province have been standing together and sharing common values and cultures through all ups and downs, tied to history.

Eight-day visit that shaped regional integrity

China hosted the 9th China-South Asia Exposition and the 29th China Kunming Import and Export Fair in Kunming, Yunnan Province, from 19 to 24 June. As a sideline event, Yunnan International Television Station organized the 4th Generation Z Lancang-Mekong Audio Visual Week 2025 from 20 to 25 June, which invited young diplomats from China’s neighbouring countries, aiming to strengthen regional integrity by reciprocal learning.

The eight-day programme brought together a total of 15 young diplomats from Mekong Region countries, as well as from maritime Southeast Asian nations like Malaysia and Indonesia, and South Asian countries such as Pakistan and Nepal, to participate in the project of creation camp project, aiming to expand cultural integrity among Asian civilizations. I was one of the participants to join it as a Myanmar media representative.

From my perspective, the whole program was designed to share knowledge of or exchange traditions, cultures and histories that have been upheld by Yunnan people up to these days since prehistoric time with Yunnan’s neighbouring Asian friends. Hence, it was fostering the comprehensive principles of the Chinese proposed Global Civilization Initiatives (GCI).

Essential means of the GCI can be interpreted as upholding humanity, respecting diversity of civilizations and inheritances, which in turn, promotes robust international people-to-people exchange. Understanding the versatile attitudes of different communities encourages harmonious cooperation while seeking a peaceful global order. Rejecting coercively exporting the phenomenon of ‘globalization’ with main adverse products: ‘Clash of Civilizations’ or ‘Cultural Shock’, the GCI emphasizes mutually exchanging social norms and common values under mutual learning. In these ways, the GCI aims to shape a global, peaceful environment with mutual respect.

Bound by nature to be the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation

Sightseeing picturesque natural landscapes and learning about the cultural diversity in Yunnan during the trip gave me of Asian countries, especially southern China, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam, sharing the same origins of continental resources with mountains, hills and rivers. Consequently, common cultural habits, ancestral rituals and social norms are being shared particularly within their closely related ethnical tribes of mainland Southeast Asia.

These shared cultural and geographical heritages reflect core values of the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation and the unity of the region.

Learning hotspots in the 4th Generation Z Lancang-Mekong Audio Visual Week 2025 were Chinese tea culture and tea history, and Yunnan’s Dai ethnic heritage, specifically in Pu’er and Xishuangbanna cities. In addition to them, the young Asian diplomats also partially studied the culturally related economic development of the province, and the fruitful hub in trade and transport of the China-Laos Railway.

Myanmar-Yunnan’s shared history from the Tea Horse Road to the CMEC

Pu’er City, the hidden paradise in Yunnan Province and is renowned as China’s tea capital, and has extensive tea plantations in both traditional and modern technologies. It could be learned that the city contributes a significant effort in China’s securing UNESCO heritage recognition of tea by advancing in research and development.

In 2022, UNESCO inscribed Chinese tea, its associated cultural practices like traditional tea processing techniques, China’s historical significance of tea, and its social importance in the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. China’s achievement of the intangible cultural heritage of tea at UNESCO is an earnest worthy.

Pu’er played a key role in tea trading back in many centuries ago as part of the ancient Chinese Silk Road to the west. To my knowledge, Myanmar was observed as one of Pu’er’s destinations in the Ancient Tea Horse Road, which started in the Tang Dynasty; then, flourished in the Ming Dynasty and Qing Dynasty.

Not only in the ancient Chinese Silk Road, Myanmar and China’s Yunnan Province also play key roles as the ‘China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC)’ in part of the modern-day Belt and Road Initiative. The project includes high-speed railways and highways by connecting Myanmar’s Kyaukphyu in Rakhine State through Mandalay, Lashio and Muse to Kunming in Yunnan. Extending to Yangon, the strategically proposed project is envisioned to promote regional economic integration and development. By these means, the regional GDP Index is expected to experience a big jump.

Pu’er’s educational support for Myanmar

Bound by history, China’s Yunnan Province and Myanmar have shared mutual coexistence in successive eras. Education is another key sector that fosters strong ties between the two countries.

I had the opportunity to visit Pu’er University during the programme, where approximately 20 Myanmar students are studying different subjects with Chinese scholarships.

“Every year, we have several Myanmar students. They are very good at Chinese and hardworking in their studies. All Myanmar students in Pu’er University are studying with different ranks of scholarships. Computer Science, Chinese Education, Mathematics and Management are the most favourite majors chosen by the Myanmar students,” said Director of the Office of International Cooperation and Exchange at Pu’er University, Mr Bai Leigang, adding that Pu’er University has a strong tie with Myanmar’s University of Yangon and the Yangon University of Foreign Languages. Both sides engage in annual student exchange programs and hold online meetings to strengthen their academic cooperation.

At present, China offers a range of government scholarships for Myanmar students, including the Chinese Government Scholarship (CSC), ASEAN-China Young Leaders Scholarship, Confucius Institute Scholarship/ Chinese Language Study Scholarships, Yunnan Provincial Government Scholarships, University-Specific Scholarships, and Silk Road Scholarship Program.

Furthermore, during the official visit of Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, Prime Minister and State Administration Council Chairman of Myanmar, to China last year in November, China pledged to provide more scholarship programs for Myanmar students shortly.

Myanmar, Yunnan stand together through all ups and downs

Last but not least, in the recent earthquake which hit Myanmar on 28 March 2025, China was the country that arrived in Myanmar the very first among international rescue operations. Sharing the borderline, the first Chinese rescue team with 32 members with rescue equipment from Yunnan Province arrived in Myanmar within 17 hours after the quake. It evidenced the strong solidarity existing between Myanmar and China, sharing weal and woe, particularly in the hardship times.

GNLM

In human life, age has always been a noticeable aspect from the very beginning. From the moment a person is born, the process of ageing day by day is a natural phenomenon that every human inevitably experiences. Growing up, maturing, and ageing are generally interconnected processes that continue along the same path. Just like a heavenly clock ticking within the human body, age never comes to a stop. Since there is no way to halt the passage of time or prevent ageing, the natural process known as “growing old” becomes an unavoidable reality for everyone.

In human life, age has always been a noticeable aspect from the very beginning. From the moment a person is born, the process of ageing day by day is a natural phenomenon that every human inevitably experiences. Growing up, maturing, and ageing are generally interconnected processes that continue along the same path. Just like a heavenly clock ticking within the human body, age never comes to a stop. Since there is no way to halt the passage of time or prevent ageing, the natural process known as “growing old” becomes an unavoidable reality for everyone.

Generally, even an inanimate object like a building, once constructed to standard, gradually becomes stronger and more solid over the first forty years or so after completion. However, after that period, over the next forty years or so, it tends to gradually lose its strength and begin to deteriorate and show signs of wear and damage.

Therefore, in both the animate and inanimate worlds, the process of gradual decay after coming into existence is an inevitable Universal law. The Lord Buddha taught that Uppāda (arising), Ṭhiti (existence), and Bhaṅga (dissolution) are the Universal truths that apply to all things – living or non-living – in this world. Everything that arises must exist for a time and eventually decay. This is an unchanging and eternal law of nature.

Starting from birth

When a person is born, their genetic inheritance and environmental conditions can influence many aspects of their development, including their growth, health, lifespan, and various personal characteristics. The beginning of life after birth marks the entry into early childhood, during which numerous changes occur in the human body in tandem with age. For example, brain development, the growth of bones and joints, and the activation of the hormonal system all take place during this period.

As the processes of a living being have already begun, the development of the body takes place during a period of strength and vitality. However, even during childhood, a time when the rate of cell growth and development is at its peak, if closely observed, one can see that cell death and degeneration are also occurring simultaneously. It is simply because the rate of cell generation is so high during this period that the damage or loss is not visibly apparent.

Therefore, it can be understood that even in early childhood, when growth and youthful development are actively taking place, the process of ageing and decline has already begun. Generally, during this stage, while the body is still embracing growth and vitality, it is also beginning to accept the gradual onset of ageing and deterioration.

From the Age of Childhood to Adolescence

Childhood and adolescence are the periods during which physical and mental development occurs most rapidly. Learning, social interaction, and personal imagination become increasingly strong and well-formed. During this time, many opportunities and possibilities open up for an individual. Parents and guardians play a key role in nurturing and guiding both the physical and emotional growth of the child. With the provision of nutritious and well-balanced food, children gradually grow and develop during these early stages of life.

However, this stage of life also marks the initial signs of ageing. For example, after reaching the peak of one’s abilities, declines may begin to appear in areas such as visual clarity, cognitive sharpness, and sensory functions. Since the body has begun to operate its functional systems, energy and vitality are actively being produced, but at the same time, waste and by-products are also being generated. These discarded elements are removed by the body either because they are no longer needed, no longer useful, or have deteriorated due to ageing.

Young Adulthood and Working Life

For an individual, the most important period in terms of career and livelihood is adulthood. This stage marks the time when one begins to gain the capacity to work for own survival. It is the age when people must start earning an income to support their basic needs, such as food, clothing, and shelter. It is also essential for maintaining a respectable and capable standing within society. Furthermore, according to the natural order, in order to keep the body which is functioning in balance and to remain actively engaged in life’s struggles, it becomes necessary for any healthy person to begin working during this stage of life.

In a sense, this stage of life represents the period during which a person’s identity, success, and way of living become clearly defined. It is the age at which one feels the need or the desire to show off their abilities and prove themselves equal to others in their communities. It is also the time to begin striving with full effort, using every ounce of strength and capability. As a result, both physical and mental aspects tend to improve and develop during this period.

However, the early signs of ageing do not disappear during this stage – they persist quietly. Although it may seem like one is growing and progressing strongly, internal physical decline is already occurring day by day. The deterioration goes largely unnoticed simply because the development is so dominant and visible. Nonetheless, a gradual decrease in actual physical capacity and mental activity – often caused by stress – Indicates that the time has come to begin preparing for eventual rest, both physically and mentally.

Ageing and Growing Old

According to certain definitions, ageing is considered to begin at around the age of 60, when a person is typically regarded as elderly. However, ageing does not depend solely on reaching that age – it is also significantly influenced by one’s physical strength, brain function, and emotional state. Since every individual has a different physical constitution, their resilience when facing life’s challenges also varies. Some people may visibly experience signs of ageing at an earlier stage. Those who have had to work intensively in search of a livelihood may encounter physical deterioration and loss of vitality sooner than others.

While medical intervention may temporarily slow down the ageing process, in general, factors such as the environment, climate, diet, lifestyle, and mental discipline all contribute to the inevitability of ageing. At this stage of life, people begin to clearly and inevitably experience the effects of growing old.

By human nature, the cells within the body gradually begin to slow down in their functioning. Signs such as weakened bones, reduced blood circulation, and declining cognitive ability are clear indicators of ageing. Whether due to personal choices, environmental factors, or external causes, people of any age can experience illnesses. However, during periods of rapid bodily development, the effects of ageing may not be noticeable. But once a certain age is reached, the signs of physical decline become increasingly evident and inescapable.

Ageing is said to occur when the body can no longer regenerate or replenish its lost physical components in time. Generally, in tropical regions of the world, noticeable signs of ageing begin to appear in individuals after the age of forty.

Ageing is not simply an ordinary health issue, but rather a natural progression that occurs as part of life. As previously explained, anything – living or non-living – that comes into existence begins to deteriorate and decay from the moment it exists. Ageing reflects this universal truth. Moreover, factors such as one’s natural environment, genetic inheritance, environmental exposures, diet, and lifestyle choices all play significant roles in either accelerating or slowing down the ageing process.

Ageing and Mental Health

Ageing affects not only the body but also the mind. As a person grows older, they may begin to feel that their self-worth is declining. Feelings of reduced affection or attention from family members can lead to emotional stress and a sense of loneliness. Therefore, maintaining social connections and having access to mental health support become increasingly important during this stage of life.

Facing Ageing in the Best Way Possible

Although ageing cannot be prevented, it can be managed. A balanced diet, healthy recreational habits, regular physical exercise, a peaceful mindset, and strong social connections can all help ease the experience of ageing in human life. Today, advancements in medical science also support healthier and longer lifespans.

Moreover, engaging in one’s religious or spiritual practices can help individuals reflect on and accept ageing as a natural process, even if it doesn’t stop it. Growing old should not be a cause for discouragement; rather, experiencing ageing offers the chance to prepare for the later stages of life before death. It also provides the opportunity to share personal experiences and wisdom with younger generations.

Living with Dignity alongside Longevity

Ageing is not the end of life. It is a combination of wisdom, experience, understanding, and love accumulated throughout a person’s life. In today’s world, the concept of “Active Ageing” helps people of all races and backgrounds to continue participating actively in society as they grow older. For example, many individuals who have retired from their jobs continue to work as doctors, teachers, or advisors, not because of their age, but because of their skills and abilities.

Although ageing is an unstoppable natural process, one can still live their life with closeness and pride during this time. The most important thing is that it is not necessary to constantly worry about ageing. Instead, one should understand that the passage of time and growing older are an essential part of life as a whole. Just as time cannot be stopped, neither can ageing.

GNLM

In human life, age has always been a noticeable aspect from the very beginning. From the moment a person is born, the process of ageing day by day is a natural phenomenon that every human inevitably experiences. Growing up, maturing, and ageing are generally interconnected processes that continue along the same path. Just like a heavenly clock ticking within the human body, age never comes to a stop. Since there is no way to halt the passage of time or prevent ageing, the natural process known as “growing old” becomes an unavoidable reality for everyone.

Generally, even an inanimate object like a building, once constructed to standard, gradually becomes stronger and more solid over the first forty years or so after completion. However, after that period, over the next forty years or so, it tends to gradually lose its strength and begin to deteriorate and show signs of wear and damage.

Therefore, in both the animate and inanimate worlds, the process of gradual decay after coming into existence is an inevitable Universal law. The Lord Buddha taught that Uppāda (arising), Ṭhiti (existence), and Bhaṅga (dissolution) are the Universal truths that apply to all things – living or non-living – in this world. Everything that arises must exist for a time and eventually decay. This is an unchanging and eternal law of nature.

Starting from birth

When a person is born, their genetic inheritance and environmental conditions can influence many aspects of their development, including their growth, health, lifespan, and various personal characteristics. The beginning of life after birth marks the entry into early childhood, during which numerous changes occur in the human body in tandem with age. For example, brain development, the growth of bones and joints, and the activation of the hormonal system all take place during this period.

As the processes of a living being have already begun, the development of the body takes place during a period of strength and vitality. However, even during childhood, a time when the rate of cell growth and development is at its peak, if closely observed, one can see that cell death and degeneration are also occurring simultaneously. It is simply because the rate of cell generation is so high during this period that the damage or loss is not visibly apparent.

Therefore, it can be understood that even in early childhood, when growth and youthful development are actively taking place, the process of ageing and decline has already begun. Generally, during this stage, while the body is still embracing growth and vitality, it is also beginning to accept the gradual onset of ageing and deterioration.

From the Age of Childhood to Adolescence

Childhood and adolescence are the periods during which physical and mental development occurs most rapidly. Learning, social interaction, and personal imagination become increasingly strong and well-formed. During this time, many opportunities and possibilities open up for an individual. Parents and guardians play a key role in nurturing and guiding both the physical and emotional growth of the child. With the provision of nutritious and well-balanced food, children gradually grow and develop during these early stages of life.

However, this stage of life also marks the initial signs of ageing. For example, after reaching the peak of one’s abilities, declines may begin to appear in areas such as visual clarity, cognitive sharpness, and sensory functions. Since the body has begun to operate its functional systems, energy and vitality are actively being produced, but at the same time, waste and by-products are also being generated. These discarded elements are removed by the body either because they are no longer needed, no longer useful, or have deteriorated due to ageing.

Young Adulthood and Working Life

For an individual, the most important period in terms of career and livelihood is adulthood. This stage marks the time when one begins to gain the capacity to work for own survival. It is the age when people must start earning an income to support their basic needs, such as food, clothing, and shelter. It is also essential for maintaining a respectable and capable standing within society. Furthermore, according to the natural order, in order to keep the body which is functioning in balance and to remain actively engaged in life’s struggles, it becomes necessary for any healthy person to begin working during this stage of life.

In a sense, this stage of life represents the period during which a person’s identity, success, and way of living become clearly defined. It is the age at which one feels the need or the desire to show off their abilities and prove themselves equal to others in their communities. It is also the time to begin striving with full effort, using every ounce of strength and capability. As a result, both physical and mental aspects tend to improve and develop during this period.

However, the early signs of ageing do not disappear during this stage – they persist quietly. Although it may seem like one is growing and progressing strongly, internal physical decline is already occurring day by day. The deterioration goes largely unnoticed simply because the development is so dominant and visible. Nonetheless, a gradual decrease in actual physical capacity and mental activity – often caused by stress – Indicates that the time has come to begin preparing for eventual rest, both physically and mentally.

Ageing and Growing Old

According to certain definitions, ageing is considered to begin at around the age of 60, when a person is typically regarded as elderly. However, ageing does not depend solely on reaching that age – it is also significantly influenced by one’s physical strength, brain function, and emotional state. Since every individual has a different physical constitution, their resilience when facing life’s challenges also varies. Some people may visibly experience signs of ageing at an earlier stage. Those who have had to work intensively in search of a livelihood may encounter physical deterioration and loss of vitality sooner than others.

While medical intervention may temporarily slow down the ageing process, in general, factors such as the environment, climate, diet, lifestyle, and mental discipline all contribute to the inevitability of ageing. At this stage of life, people begin to clearly and inevitably experience the effects of growing old.

By human nature, the cells within the body gradually begin to slow down in their functioning. Signs such as weakened bones, reduced blood circulation, and declining cognitive ability are clear indicators of ageing. Whether due to personal choices, environmental factors, or external causes, people of any age can experience illnesses. However, during periods of rapid bodily development, the effects of ageing may not be noticeable. But once a certain age is reached, the signs of physical decline become increasingly evident and inescapable.

Ageing is said to occur when the body can no longer regenerate or replenish its lost physical components in time. Generally, in tropical regions of the world, noticeable signs of ageing begin to appear in individuals after the age of forty.

Ageing is not simply an ordinary health issue, but rather a natural progression that occurs as part of life. As previously explained, anything – living or non-living – that comes into existence begins to deteriorate and decay from the moment it exists. Ageing reflects this universal truth. Moreover, factors such as one’s natural environment, genetic inheritance, environmental exposures, diet, and lifestyle choices all play significant roles in either accelerating or slowing down the ageing process.

Ageing and Mental Health

Ageing affects not only the body but also the mind. As a person grows older, they may begin to feel that their self-worth is declining. Feelings of reduced affection or attention from family members can lead to emotional stress and a sense of loneliness. Therefore, maintaining social connections and having access to mental health support become increasingly important during this stage of life.

Facing Ageing in the Best Way Possible

Although ageing cannot be prevented, it can be managed. A balanced diet, healthy recreational habits, regular physical exercise, a peaceful mindset, and strong social connections can all help ease the experience of ageing in human life. Today, advancements in medical science also support healthier and longer lifespans.

Moreover, engaging in one’s religious or spiritual practices can help individuals reflect on and accept ageing as a natural process, even if it doesn’t stop it. Growing old should not be a cause for discouragement; rather, experiencing ageing offers the chance to prepare for the later stages of life before death. It also provides the opportunity to share personal experiences and wisdom with younger generations.

Living with Dignity alongside Longevity

Ageing is not the end of life. It is a combination of wisdom, experience, understanding, and love accumulated throughout a person’s life. In today’s world, the concept of “Active Ageing” helps people of all races and backgrounds to continue participating actively in society as they grow older. For example, many individuals who have retired from their jobs continue to work as doctors, teachers, or advisors, not because of their age, but because of their skills and abilities.

Although ageing is an unstoppable natural process, one can still live their life with closeness and pride during this time. The most important thing is that it is not necessary to constantly worry about ageing. Instead, one should understand that the passage of time and growing older are an essential part of life as a whole. Just as time cannot be stopped, neither can ageing.

GNLM

Rare earth elements (REEs) are a group of 17 metals that play a crucial role in modern technology. Despite their name, they are relatively abundant in the Earth’s crust but are rarely found in concentrated forms. These elements include lanthanides plus scandium and yttrium. REEs are essential in producing high-performance magnets, batteries, LED lights, and electronics such as smartphones and electric vehicles. They’re also used in green energy technologies like wind turbines and solar panels.

Rare earth elements (REEs) are a group of 17 metals that play a crucial role in modern technology. Despite their name, they are relatively abundant in the Earth’s crust but are rarely found in concentrated forms. These elements include lanthanides plus scandium and yttrium. REEs are essential in producing high-performance magnets, batteries, LED lights, and electronics such as smartphones and electric vehicles. They’re also used in green energy technologies like wind turbines and solar panels. Mining and refining rare earths can be challenging due to environmental concerns and geopolitical factors, making their supply chain complex. As global demand increases, sustainable methods of extraction and recycling are being explored to reduce environmental impact and secure future availability.

Rare Earth Mining in Kachin State, Myanmar

Kachin State in northern Myanmar has become a major hub for rare earth element (REE) extraction, especially since 2017. The region, particularly areas like Chipwi and Pangwa near the China border, hosts hundreds of mining sites that produce valuable heavy rare earths such as dysprosium and terbium, which are critical for high-tech and green energy industries.

After 2021, mining activity surged dramatically, with Myanmar supplying up to 60-87 per cent of China’s rare earth imports during some years. However, this boom has come at a cost: unregulated mining has led to deforestation, water pollution, and health risks for local communities. Many operations are linked to armed groups and lack proper oversight, raising concerns about environmental damage and human rights violations.

Myanmar’s rare earth production now ranks among the top globally, but the social and ecological impacts in Kachin State remain deeply troubling. The rapid expansion of mining – often driven by demand from neighbouring countries – has led to the destruction of forests, contamination of rivers and soil, and displacement of local communities. Toxic chemicals used in the extraction process have damaged ecosystems and endangered biodiversity, while the lack of regulation and accountability has made it difficult to monitor or mitigate these effects. Moreover, many mining operations are associated with armed groups or operate without formal oversight, fueling conflict and undermining peace efforts in the region. As Myanmar’s role in the global rare earth supply chain grows, calls for more transparent, ethical, and environmentally responsible practices continue to intensify.

Step-by-Step Overview of Rare Earth Mining in Kachin State, Myanmar

Rare earth mining in Kachin State typically follows a process known as in-situ leaching, which is both cost-effective and environmentally risky. Here’s how it unfolds:

Site Selection & Clearing: Mining companies or armed groups identify mountain slopes rich in heavy rare earths like dysprosium and terbium. Forests are cleared, and access roads are built, often without environmental assessments.

Chemical Injection: Workers drill holes into the mountains and inject chemicals such as ammonium sulfate and oxalic acid into the soil. These dissolve the rare earth elements underground.

Collection Ponds: The chemical-laced solution flows downhill into large open-air ponds, where the rare earth sludge is collected. These ponds often leak, contaminating nearby rivers and farmland.

Drying & Transport: The sludge is dried in wood-fired kilns, then packed and transported, mostly across the border to China for processing. Myanmar supplies up to 60-87 per cent of China’s heavy rare earth imports.

Local Impact: Mining sites are often unregulated. Workers lack protective gear, and communities face deforestation, water pollution, and health issues. Armed groups control many operations, taxing miners and fueling conflict.

This process has transformed Kachin into a global rare earth hotspot, but at a steep social and ecological cost.

Environmental and Ecological Damage in Kachin State from Rare Earth Mining

The rapid expansion of rare earth mining in Kachin State has caused severe harm to the region’s natural beauty and ecological balance. Once lush forests have been cleared to make way for mining sites, leading to widespread deforestation and loss of biodiversity. Rivers and streams, once sources of clean water, are now polluted with toxic chemicals like ammonium sulfate, arsenic, and cadmium, which are used in the extraction process. These contaminants have seeped into the soil and water systems, threatening aquatic life and making water unsafe for drinking and farming.

The scenic mountain landscapes have been scarred by open pits and chemical ponds, while landslides and soil erosion have become more frequent due to weakened terrain. Wildlife habitats have been destroyed, forcing animals to flee or perish. Indigenous communities that depend on the land for agriculture and fishing face declining crop yields and health risks. The damage is not only environmental — it’s cultural and social, as the destruction of nature undermines traditional ways of life and spiritual connections to the land.

Unequal Gains from Rare Earth Mining in Myanmar

Although rare earth mining in Kachin State has generated billions in export revenue, the benefits are distributed in a highly unequal manner. Local communities that suffer the brunt of environmental degradation receive little to no direct compensation. Their farmlands are contaminated, water sources are polluted, and traditional livelihoods are destroyed. Many residents face health issues, displacement, and social instability while lacking access to clean water, healthcare, or education.

In contrast, armed groups and private companies operating the mines reap substantial profits. The former imposes taxes of up to $4,800 per tonne of exported rare earths, using some of the revenue for infrastructure and services in resistance-held areas. However, transparency is limited, and much of the wealth remains concentrated among elites and intermediaries.

The Myanmar government itself gains little, as most mining is unregulated and untaxed, bypassing official channels. This creates a stark divide: while Myanmar ranks among the top global producers of rare earths, the majority of its people, especially those in mining zones, see few lasting benefits. The imbalance highlights the urgent need for responsible governance, equitable revenue sharing, and environmental safeguards.

Final Reflection from the Perspective of Kachin Communities

For the people of Kachin State, rare earth mining has brought more loss than gain. Their once-pristine environment has turned into a scarred landscape of chemical ponds and dying rivers. Traditional ways of life rooted in agriculture, fishing, and reverence for nature have been eroded. Though vast wealth flows through their land, it rarely reaches their hands. The daily reality for many is polluted water, poor health, and displacement, while powerful groups profit unchecked.

The writer would like to urge the responsible organizations – both domestic and international – to implement transparent regulations, promote sustainable mining practices, and ensure fair compensation for affected communities. Local voices must be included in decision-making, and rehabilitation of damaged ecosystems must begin immediately.

If these destructive trends continue without reform, Kachin’s environmental and social fabric may be irreversibly damaged. But with inclusive governance, ethical oversight, and global attention, there’s still hope for Kachin to transform its mineral wealth into a force for community well-being and ecological resilience.

GNLM

Rare earth elements (REEs) are a group of 17 metals that play a crucial role in modern technology. Despite their name, they are relatively abundant in the Earth’s crust but are rarely found in concentrated forms. These elements include lanthanides plus scandium and yttrium. REEs are essential in producing high-performance magnets, batteries, LED lights, and electronics such as smartphones and electric vehicles. They’re also used in green energy technologies like wind turbines and solar panels. Mining and refining rare earths can be challenging due to environmental concerns and geopolitical factors, making their supply chain complex. As global demand increases, sustainable methods of extraction and recycling are being explored to reduce environmental impact and secure future availability.

Rare Earth Mining in Kachin State, Myanmar

Kachin State in northern Myanmar has become a major hub for rare earth element (REE) extraction, especially since 2017. The region, particularly areas like Chipwi and Pangwa near the China border, hosts hundreds of mining sites that produce valuable heavy rare earths such as dysprosium and terbium, which are critical for high-tech and green energy industries.

After 2021, mining activity surged dramatically, with Myanmar supplying up to 60-87 per cent of China’s rare earth imports during some years. However, this boom has come at a cost: unregulated mining has led to deforestation, water pollution, and health risks for local communities. Many operations are linked to armed groups and lack proper oversight, raising concerns about environmental damage and human rights violations.

Myanmar’s rare earth production now ranks among the top globally, but the social and ecological impacts in Kachin State remain deeply troubling. The rapid expansion of mining – often driven by demand from neighbouring countries – has led to the destruction of forests, contamination of rivers and soil, and displacement of local communities. Toxic chemicals used in the extraction process have damaged ecosystems and endangered biodiversity, while the lack of regulation and accountability has made it difficult to monitor or mitigate these effects. Moreover, many mining operations are associated with armed groups or operate without formal oversight, fueling conflict and undermining peace efforts in the region. As Myanmar’s role in the global rare earth supply chain grows, calls for more transparent, ethical, and environmentally responsible practices continue to intensify.

Step-by-Step Overview of Rare Earth Mining in Kachin State, Myanmar

Rare earth mining in Kachin State typically follows a process known as in-situ leaching, which is both cost-effective and environmentally risky. Here’s how it unfolds:

Site Selection & Clearing: Mining companies or armed groups identify mountain slopes rich in heavy rare earths like dysprosium and terbium. Forests are cleared, and access roads are built, often without environmental assessments.

Chemical Injection: Workers drill holes into the mountains and inject chemicals such as ammonium sulfate and oxalic acid into the soil. These dissolve the rare earth elements underground.

Collection Ponds: The chemical-laced solution flows downhill into large open-air ponds, where the rare earth sludge is collected. These ponds often leak, contaminating nearby rivers and farmland.

Drying & Transport: The sludge is dried in wood-fired kilns, then packed and transported, mostly across the border to China for processing. Myanmar supplies up to 60-87 per cent of China’s heavy rare earth imports.

Local Impact: Mining sites are often unregulated. Workers lack protective gear, and communities face deforestation, water pollution, and health issues. Armed groups control many operations, taxing miners and fueling conflict.

This process has transformed Kachin into a global rare earth hotspot, but at a steep social and ecological cost.

Environmental and Ecological Damage in Kachin State from Rare Earth Mining

The rapid expansion of rare earth mining in Kachin State has caused severe harm to the region’s natural beauty and ecological balance. Once lush forests have been cleared to make way for mining sites, leading to widespread deforestation and loss of biodiversity. Rivers and streams, once sources of clean water, are now polluted with toxic chemicals like ammonium sulfate, arsenic, and cadmium, which are used in the extraction process. These contaminants have seeped into the soil and water systems, threatening aquatic life and making water unsafe for drinking and farming.

The scenic mountain landscapes have been scarred by open pits and chemical ponds, while landslides and soil erosion have become more frequent due to weakened terrain. Wildlife habitats have been destroyed, forcing animals to flee or perish. Indigenous communities that depend on the land for agriculture and fishing face declining crop yields and health risks. The damage is not only environmental — it’s cultural and social, as the destruction of nature undermines traditional ways of life and spiritual connections to the land.

Unequal Gains from Rare Earth Mining in Myanmar

Although rare earth mining in Kachin State has generated billions in export revenue, the benefits are distributed in a highly unequal manner. Local communities that suffer the brunt of environmental degradation receive little to no direct compensation. Their farmlands are contaminated, water sources are polluted, and traditional livelihoods are destroyed. Many residents face health issues, displacement, and social instability while lacking access to clean water, healthcare, or education.

In contrast, armed groups and private companies operating the mines reap substantial profits. The former imposes taxes of up to $4,800 per tonne of exported rare earths, using some of the revenue for infrastructure and services in resistance-held areas. However, transparency is limited, and much of the wealth remains concentrated among elites and intermediaries.

The Myanmar government itself gains little, as most mining is unregulated and untaxed, bypassing official channels. This creates a stark divide: while Myanmar ranks among the top global producers of rare earths, the majority of its people, especially those in mining zones, see few lasting benefits. The imbalance highlights the urgent need for responsible governance, equitable revenue sharing, and environmental safeguards.

Final Reflection from the Perspective of Kachin Communities

For the people of Kachin State, rare earth mining has brought more loss than gain. Their once-pristine environment has turned into a scarred landscape of chemical ponds and dying rivers. Traditional ways of life rooted in agriculture, fishing, and reverence for nature have been eroded. Though vast wealth flows through their land, it rarely reaches their hands. The daily reality for many is polluted water, poor health, and displacement, while powerful groups profit unchecked.

The writer would like to urge the responsible organizations – both domestic and international – to implement transparent regulations, promote sustainable mining practices, and ensure fair compensation for affected communities. Local voices must be included in decision-making, and rehabilitation of damaged ecosystems must begin immediately.

If these destructive trends continue without reform, Kachin’s environmental and social fabric may be irreversibly damaged. But with inclusive governance, ethical oversight, and global attention, there’s still hope for Kachin to transform its mineral wealth into a force for community well-being and ecological resilience.

GNLM

In the Yangon of the 1960s and 70s, where one-storey homes lined quiet streets and private cars were a rare luxury, a unique sporting tradition thrived in the heart of our communities. It wasn’t played in stadiums or watched on television. It lived in the lanes of Kyaukmyaung Ward, Tamwe Township, and was known simply and fondly as the W (Double U) football match.

In the Yangon of the 1960s and 70s, where one-storey homes lined quiet streets and private cars were a rare luxury, a unique sporting tradition thrived in the heart of our communities. It wasn’t played in stadiums or watched on television. It lived in the lanes of Kyaukmyaung Ward, Tamwe Township, and was known simply and fondly as the W (Double U) football match.

We didn’t know what the “W” stood for—it might have come from a brand or marking on the ball itself. What mattered more was what it meant to us: a small-sized football game, fast-paced and fiercely loved. The W ball was smaller than a regular one, perfect for the 20-foot-wide streets that served as our playgrounds. With no cars, no shops, and few passersby, those streets became our open fields. Dagon Thiri Street, Thadipahtan Street, Myothit 1 Street, and Kyakwetthit Street were the heartlands of this joyful tradition.

Our matches had simple but unique rules. Teams were made up of three or four players, and the most important condition: you had to be under four feet nine inches tall to play. This rule ensured that the game belonged to children, mostly 13- and 14-year-olds like I was then. The taller boys, even the talented ones, had to sit out. We guarded that boundary proudly. It was a game of and/or for our age.

At the time, I was attending Basic Education State High School 5, Tamwe (BEHS 5), just a short walk from our home on Dagon Thiri Street. Most of my teammates were also my classmates. We studied together, played together, and grew up together. After passing the eighth standard, I moved to Basic Education State High School 2, Tamwe (BEHS 2), which was even closer to our house.

Outside the official community tournaments, we played W football almost every day, especially during the Rainy Season, one of the three seasons in Myanmar, along with Summer (the Hot Season) and the Cold Season. The Rainy Season was our favourite. Slippery streets, flying mud, wet hair, and laughter; it was pure joy. And when the matches were over, we went home drenched and smiling, sometimes limping, but always fulfilled.

The goals for official tournaments were carefully built by organizers, using wood frames and cotton nets, and later, iron frames replaced the wood. On regular days, we made our own: using bricks, schoolbags, slippers, or whatever was around. The creativity was part of the fun. We didn’t need standard gear – we just needed space, a W ball, and each other.

These weren’t just neighbourhood kickabouts. Community tournaments were held regularly, with shields and trophies for the winners. Kids from other townships came to play. I still remember the thrill of competing, the cheers of neighbours, and the pride of representing your street or groups of friends. My friends and I – our team – won first prize two or three times. Those trophies weren’t just metal and wood. They were symbols of belonging, friendship, and youthful triumph.

Kyaukmyaung back then was different. Most houses were one-storey, with just a few two-storey homes scattered about. Families who owned private cars usually kept them in godowns or garages inside their compounds. My grandparents lived in a two-storey house – part woodpile, part concrete – on Kyaukmyaung Street, just steps from our home on Dagon Thiri Street. They owned a Holden car, a European model, I believe. On Sundays, we would drive around Yangon with them – a memory I still cherish. They passed away when I was still young, sometime during the late 1960s or 70s. That house is now gone, but I live in the apartment building that stands in its place – a living link to the past.

Today’s Kyaukmyaung looks very different. The humble one-storey homes have mostly disappeared, replaced by apartment buildings constructed by private developers. The open lanes are narrower, busier and more crowded. The streets where we once dived for the ball or sprinted in bare feet are no longer free of cars or noise. The W ball is nowhere to be found in shops. The game has vanished – quietly, without fanfare – just like the old brick goalposts and wooden shields.

But to those of us who played it, the W football match remains alive in memory. It was our game, our community’s invention, shaped by the spaces we had and the dreams we held. We learned how to work as a team, how to lose with grace and win with modest pride. We didn’t need coaches or uniforms – just friendships, laughter, and a ball.

Today, our sons, daughters, and grandchildren grow up in a very different world – one filled with digital games, smartphones, tablets, and online competitions. They build teams on screens, play matches in virtual stadiums, and win battles without stepping outside. While technology brings new forms of entertainment, I sometimes wonder what they might be missing: the thrill of kicking a ball under the rain, the warmth of shared laughter on sun-soaked streets, and the unspoken bond formed when you pass, run, and score together – on real ground, with real friends.

Some games are never televised, never rcorded, and never return. But the best ones don’t need to. They live on, wherever we remember them.

GNLM

In the Yangon of the 1960s and 70s, where one-storey homes lined quiet streets and private cars were a rare luxury, a unique sporting tradition thrived in the heart of our communities. It wasn’t played in stadiums or watched on television. It lived in the lanes of Kyaukmyaung Ward, Tamwe Township, and was known simply and fondly as the W (Double U) football match.

We didn’t know what the “W” stood for—it might have come from a brand or marking on the ball itself. What mattered more was what it meant to us: a small-sized football game, fast-paced and fiercely loved. The W ball was smaller than a regular one, perfect for the 20-foot-wide streets that served as our playgrounds. With no cars, no shops, and few passersby, those streets became our open fields. Dagon Thiri Street, Thadipahtan Street, Myothit 1 Street, and Kyakwetthit Street were the heartlands of this joyful tradition.

Our matches had simple but unique rules. Teams were made up of three or four players, and the most important condition: you had to be under four feet nine inches tall to play. This rule ensured that the game belonged to children, mostly 13- and 14-year-olds like I was then. The taller boys, even the talented ones, had to sit out. We guarded that boundary proudly. It was a game of and/or for our age.

At the time, I was attending Basic Education State High School 5, Tamwe (BEHS 5), just a short walk from our home on Dagon Thiri Street. Most of my teammates were also my classmates. We studied together, played together, and grew up together. After passing the eighth standard, I moved to Basic Education State High School 2, Tamwe (BEHS 2), which was even closer to our house.

Outside the official community tournaments, we played W football almost every day, especially during the Rainy Season, one of the three seasons in Myanmar, along with Summer (the Hot Season) and the Cold Season. The Rainy Season was our favourite. Slippery streets, flying mud, wet hair, and laughter; it was pure joy. And when the matches were over, we went home drenched and smiling, sometimes limping, but always fulfilled.

The goals for official tournaments were carefully built by organizers, using wood frames and cotton nets, and later, iron frames replaced the wood. On regular days, we made our own: using bricks, schoolbags, slippers, or whatever was around. The creativity was part of the fun. We didn’t need standard gear – we just needed space, a W ball, and each other.

These weren’t just neighbourhood kickabouts. Community tournaments were held regularly, with shields and trophies for the winners. Kids from other townships came to play. I still remember the thrill of competing, the cheers of neighbours, and the pride of representing your street or groups of friends. My friends and I – our team – won first prize two or three times. Those trophies weren’t just metal and wood. They were symbols of belonging, friendship, and youthful triumph.

Kyaukmyaung back then was different. Most houses were one-storey, with just a few two-storey homes scattered about. Families who owned private cars usually kept them in godowns or garages inside their compounds. My grandparents lived in a two-storey house – part woodpile, part concrete – on Kyaukmyaung Street, just steps from our home on Dagon Thiri Street. They owned a Holden car, a European model, I believe. On Sundays, we would drive around Yangon with them – a memory I still cherish. They passed away when I was still young, sometime during the late 1960s or 70s. That house is now gone, but I live in the apartment building that stands in its place – a living link to the past.

Today’s Kyaukmyaung looks very different. The humble one-storey homes have mostly disappeared, replaced by apartment buildings constructed by private developers. The open lanes are narrower, busier and more crowded. The streets where we once dived for the ball or sprinted in bare feet are no longer free of cars or noise. The W ball is nowhere to be found in shops. The game has vanished – quietly, without fanfare – just like the old brick goalposts and wooden shields.

But to those of us who played it, the W football match remains alive in memory. It was our game, our community’s invention, shaped by the spaces we had and the dreams we held. We learned how to work as a team, how to lose with grace and win with modest pride. We didn’t need coaches or uniforms – just friendships, laughter, and a ball.

Today, our sons, daughters, and grandchildren grow up in a very different world – one filled with digital games, smartphones, tablets, and online competitions. They build teams on screens, play matches in virtual stadiums, and win battles without stepping outside. While technology brings new forms of entertainment, I sometimes wonder what they might be missing: the thrill of kicking a ball under the rain, the warmth of shared laughter on sun-soaked streets, and the unspoken bond formed when you pass, run, and score together – on real ground, with real friends.

Some games are never televised, never rcorded, and never return. But the best ones don’t need to. They live on, wherever we remember them.

GNLM

Emotional pain, once felt, rarely disappears. Trauma, especially in childhood or youth, sinks deep into the psyche, shaping how people think, feel, and act. Even when memories dim, the emotional weight remains, flaring up as sudden anger, fear, or despair that feels out of place but is rooted in long-forgotten wounds.

Emotional pain, once felt, rarely disappears. Trauma, especially in childhood or youth, sinks deep into the psyche, shaping how people think, feel, and act. Even when memories dim, the emotional weight remains, flaring up as sudden anger, fear, or despair that feels out of place but is rooted in long-forgotten wounds.

The early years are crucial. When children grow up in fear, neglect, or violence, their emotional systems learn to survive, not thrive. These survival habits can harden into lifelong patterns, quietly steering relationships, choices, and self-worth. Without awareness, the past becomes an invisible puppeteer.

Nowhere is this more urgent than in Myanmar. A generation of young people has been shaped not by peace but by the trauma of an unnecessary war. They carry invisible scars of lost safety, broken trust, and interrupted futures. These wounds may not bleed, but they fester silently, threatening to poison the nation’s future.

To rebuild a country while ignoring the emotional damage to its people is like planting new crops in scorched earth. You may see green shoots, but the soil remains wounded, dry, brittle, and unable to nourish real growth.

True national healing cannot come through infrastructure alone. Roads and buildings can be repaired. Minds and hearts take longer, but matter more.

Myanmar’s future cannot rise on broken hearts and buried pain. A nation rebuilt with bricks but not with care for its wounded minds is a nation standing on a fault line.

The young, who should be dreaming, learning, and building, are instead carrying the weight of a war they never chose. If their inner world is left in ruins, no outer structure will stand for long. We must stop pretending that survival is enough. These young souls deserve more than endurance – they deserve healing, dignity, and a voice. If we truly want a free and lasting Myanmar, we must begin not just with laws or roads, but with the quiet, patient work of restoring the human spirit. Anything less is betrayal dressed as progress.

GNLM

Emotional pain, once felt, rarely disappears. Trauma, especially in childhood or youth, sinks deep into the psyche, shaping how people think, feel, and act. Even when memories dim, the emotional weight remains, flaring up as sudden anger, fear, or despair that feels out of place but is rooted in long-forgotten wounds.

The early years are crucial. When children grow up in fear, neglect, or violence, their emotional systems learn to survive, not thrive. These survival habits can harden into lifelong patterns, quietly steering relationships, choices, and self-worth. Without awareness, the past becomes an invisible puppeteer.

Nowhere is this more urgent than in Myanmar. A generation of young people has been shaped not by peace but by the trauma of an unnecessary war. They carry invisible scars of lost safety, broken trust, and interrupted futures. These wounds may not bleed, but they fester silently, threatening to poison the nation’s future.

To rebuild a country while ignoring the emotional damage to its people is like planting new crops in scorched earth. You may see green shoots, but the soil remains wounded, dry, brittle, and unable to nourish real growth.

True national healing cannot come through infrastructure alone. Roads and buildings can be repaired. Minds and hearts take longer, but matter more.

Myanmar’s future cannot rise on broken hearts and buried pain. A nation rebuilt with bricks but not with care for its wounded minds is a nation standing on a fault line.

The young, who should be dreaming, learning, and building, are instead carrying the weight of a war they never chose. If their inner world is left in ruins, no outer structure will stand for long. We must stop pretending that survival is enough. These young souls deserve more than endurance – they deserve healing, dignity, and a voice. If we truly want a free and lasting Myanmar, we must begin not just with laws or roads, but with the quiet, patient work of restoring the human spirit. Anything less is betrayal dressed as progress.

GNLM

Even just one smile on your face in a day can bring you a sense of relief and comfort. The small act known as a smile can have a profound impact in the human world and serves as a companion that speaks louder than words when it comes to living a joyful life.

Even just one smile on your face in a day can bring you a sense of relief and comfort. The small act known as a smile can have a profound impact in the human world and serves as a companion that speaks louder than words when it comes to living a joyful life.

In everyone’s life, we gradually face challenges and difficulties that can at times feel overwhelming. However, even during moments of discouragement for various reasons, a simple smile on the face can help ease our emotional state to some extent. A person’s smile can also influence the emotions of others and help reduce their mental stress.

Duo activities

Everyone happy can bring a smile, which represents satisfaction on their faces. No one can bring a smile while facing suffering and unhappiness. Hence, the smiling move and the emotion of happiness and satisfaction are inseparable. That is why individuals have to nurture their souls to be able to bring smiles by overcoming sufferings and challenges, as well as by searching root causes of happiness in life. Everybody needs to consider that if they use smiles as a tool to build a happy society, the entire world can cease unhappiness, sadness and grief.

The power of a smile

A smile is a natural and deeply valuable human behaviour that belongs to everyone. For example, when a mother smiles at her young child, that smile conveys a sense of safety and acceptance to the child. In the same way, in everyday life, a smile serves as a rustproof bridge that builds strong connections between oneself and those around them.

Scientifically speaking, when a person smiles, the body releases natural feel-good chemicals such as serotonin, dopamine, and endorphins. These substances help generate feelings of satisfaction and emotional well-being. Additionally, a smile can even help lower heart rate and reduce stress levels.

How a Smile can help us live a joyful life

Happiness is an emotion, but it doesn’t always arise automatically. Sometimes, we must make an effort to seek it out. In doing so, smiling becomes one of the simplest and most accessible ways to maintain a sense of joy in our daily lives.

Some fundamental principles underpin happiness. These include self-confidence, self-worth, the capacity to love, and even the ability to forgive those who oppose us. When combined with a genuine smile, these values play an essential role in building healthy relationships, improving mental well-being, and achieving success in life. Generally, happiness is defined as a state of emotional satisfaction. Efforts to ease social tensions and reduce feelings of loneliness are also key factors in achieving a happy and fulfilling life.

Smiles and External Relationships

In social settings, those who smile often are frequently perceived as trustworthy and approachable individuals. If you look at successful people featured in the media, you’ll often notice a bright, consistent smile on their faces. That smile helps strengthen their social relationships and serves as a valuable tool for communication and collaboration.

Someone is smiling warmly and kindly when meeting others not only reflects your attitude but also builds self-confidence. In the professional world, individuals with strong social skills tend to receive more opportunities. Therefore, a smile proves beneficial not just personally, but also in business, education, and organizational environments.

How a Smile Supports Oneself

There are times when, looking at one’s own life, a person may feel discouraged or disheartened. Due to losses, dissatisfaction, or the many challenges that arise in daily life, one might feel like giving up. Even in those moments, a simple smile can become a message of hope.

Research has shown that in mirror therapy, where individuals look at their reflection, smiling at oneself can help reduce psychological stress. Loving oneself and accepting one’s life can gradually be restored, and the starting point for that healing often begins with a single smile.

Raising a smiling habit

Smiling can be difficult to do in unwanted situations or to maintain as a habit. However, gradually making a conscious effort to smile even during challenging emotional times can help create a better mental state. Along with the points mentioned above, this can help shift the energy moving within you in a different direction. It supports becoming a person filled with love, compassion, motivation, and fulfilment.

Even during difficult and tiring times, if one can carry a smile, it can bring comfort to everyone around them and fill the entire environment with feelings of peace and happiness. By setting aside one’s pain and suffering to bring joy to others, that happiness will reflect from those people, allowing oneself to experience at least a small measure of calm and joy. This is the principle of kindness’s reciprocal nature.

Victims of unhappiness

The surveys of the World Health Organization stated that more than 300 million of the global population, accounting for 4.4 per cent, are suffering from depression in their lives, adding that a large portion of the population is also lacking happiness based to unknown diseases. As different tensions impact society, the majority of people cannot emphasize happiness and pleasure while struggling for the daily needs of their lives.

The Lord Buddha preached the Four Noble Truths. They are the first Truth of Suffering (Dukkha) that life inherently involves suffering and dissatisfaction; the second Truth of the Origin of Suffering (Samudaya) that Suffering arises from craving, attachment, and ignorance; the third Truth of the Cessation of Suffering (Nirodha) that Suffering can be overcome and ended; and the fourth Truth of the Path to the Cessation of Suffering (Magga) that the Noble Eightfold Path provides the way to end suffering.

Hence, nobody can avoid the impacts of suffering and dissatisfaction. They are facing different social crises such as a higher rate of unemployment, lower income, rising expenses and increasing commodity prices. So, the majority of people are experiencing something special about depression. It shows basic factors to disappear happiness and pleasure in their minds. Consequently, they do not believe in their future aspirations, and they cannot endure these sufferings.

Research on happiness

Various organizations in global countries released surveys and indices over findings from research on the happiness of people. The happiness of people can be measured by gross domestic product, healthy lifespan, contribution of society for individuals, rights of independent choosing, generosity, and perspectives on corruption. Especially, people from developed countries are embracing happiness due to their lifestyle, which is better than other countries.

Criteria

Life is short. Instead of feeling upset and running away during that brief time, we should face it with joy. A smile is a gift for your life – something you can use throughout your entire lifetime.

Therefore, dear friends, I encourage you not to forget to smile on your face when you wake up in the morning and to smile when you meet others. A single smile can make not only yourself but also someone else’s entire day extraordinary. A single smile can open a person’s heart. If you truly want to be someone who smiles genuinely, let’s start by sharing words of love and kindness in life.

Smiles based on happiness

The happy life of individuals does not depend on the life possessing money, wealth, educational degrees, taking pride in their lives, and faithful associates. Only when individuals are happy will they bring smiles for a long time due to enjoying the safety of life. Actually, can they be happy and satisfied only if they have sufficient food, clothing and accommodation? Both physical and mental well-being can shape the happy life of people. If so, they can sustain their satisfactory smiles throughout their lives.

GNLM

Even just one smile on your face in a day can bring you a sense of relief and comfort. The small act known as a smile can have a profound impact in the human world and serves as a companion that speaks louder than words when it comes to living a joyful life.

In everyone’s life, we gradually face challenges and difficulties that can at times feel overwhelming. However, even during moments of discouragement for various reasons, a simple smile on the face can help ease our emotional state to some extent. A person’s smile can also influence the emotions of others and help reduce their mental stress.

Duo activities

Everyone happy can bring a smile, which represents satisfaction on their faces. No one can bring a smile while facing suffering and unhappiness. Hence, the smiling move and the emotion of happiness and satisfaction are inseparable. That is why individuals have to nurture their souls to be able to bring smiles by overcoming sufferings and challenges, as well as by searching root causes of happiness in life. Everybody needs to consider that if they use smiles as a tool to build a happy society, the entire world can cease unhappiness, sadness and grief.

The power of a smile

A smile is a natural and deeply valuable human behaviour that belongs to everyone. For example, when a mother smiles at her young child, that smile conveys a sense of safety and acceptance to the child. In the same way, in everyday life, a smile serves as a rustproof bridge that builds strong connections between oneself and those around them.

Scientifically speaking, when a person smiles, the body releases natural feel-good chemicals such as serotonin, dopamine, and endorphins. These substances help generate feelings of satisfaction and emotional well-being. Additionally, a smile can even help lower heart rate and reduce stress levels.

How a Smile can help us live a joyful life

Happiness is an emotion, but it doesn’t always arise automatically. Sometimes, we must make an effort to seek it out. In doing so, smiling becomes one of the simplest and most accessible ways to maintain a sense of joy in our daily lives.

Some fundamental principles underpin happiness. These include self-confidence, self-worth, the capacity to love, and even the ability to forgive those who oppose us. When combined with a genuine smile, these values play an essential role in building healthy relationships, improving mental well-being, and achieving success in life. Generally, happiness is defined as a state of emotional satisfaction. Efforts to ease social tensions and reduce feelings of loneliness are also key factors in achieving a happy and fulfilling life.

Smiles and External Relationships

In social settings, those who smile often are frequently perceived as trustworthy and approachable individuals. If you look at successful people featured in the media, you’ll often notice a bright, consistent smile on their faces. That smile helps strengthen their social relationships and serves as a valuable tool for communication and collaboration.

Someone is smiling warmly and kindly when meeting others not only reflects your attitude but also builds self-confidence. In the professional world, individuals with strong social skills tend to receive more opportunities. Therefore, a smile proves beneficial not just personally, but also in business, education, and organizational environments.

How a Smile Supports Oneself

There are times when, looking at one’s own life, a person may feel discouraged or disheartened. Due to losses, dissatisfaction, or the many challenges that arise in daily life, one might feel like giving up. Even in those moments, a simple smile can become a message of hope.

Research has shown that in mirror therapy, where individuals look at their reflection, smiling at oneself can help reduce psychological stress. Loving oneself and accepting one’s life can gradually be restored, and the starting point for that healing often begins with a single smile.

Raising a smiling habit

Smiling can be difficult to do in unwanted situations or to maintain as a habit. However, gradually making a conscious effort to smile even during challenging emotional times can help create a better mental state. Along with the points mentioned above, this can help shift the energy moving within you in a different direction. It supports becoming a person filled with love, compassion, motivation, and fulfilment.

Even during difficult and tiring times, if one can carry a smile, it can bring comfort to everyone around them and fill the entire environment with feelings of peace and happiness. By setting aside one’s pain and suffering to bring joy to others, that happiness will reflect from those people, allowing oneself to experience at least a small measure of calm and joy. This is the principle of kindness’s reciprocal nature.

Victims of unhappiness